Nations meet in Geneva to make mercury history

Signatories to the first global treaty to rein in mercury pollution are gathered in Geneva this week to discuss how to seek further progress. Switzerland, a trader of mercury, is mulling over how to implement the convention.

The Minamata Convention, named after a Japanese fishing town where mercury was discharged into the bay by a large chemical company between 1932 and 1968, entered into force on August 16, 2017. So far, 79 states have ratified it, including the United States, China, Brazil, Indonesia, Peru and Switzerland (on May 26, 2016).

The Geneva meeting, from September 24-29, is expected to focus on a range of technical issues, such as trade and storage of mercury, management of contaminated sites, and artisanal and small-scale gold mining.

Next week’s decisions will have an impact on Switzerland, which is an important legal trader in mercury and recycler. According to a written cabinet response to a question by Green Party parliamentarian Regula Rytz, published in June, Switzerland exported 30 tonnes of mercury last year – down from 110 tonnes per year between 2011-2015.

The Federal Environment Office says Switzerland complies with most of the convention’s requirements for eliminating mercury-containing products and phasing out mercury in industrial processes. But to achieve the treaty’s ultimate aim of reducing mercury use around the world, changes are needed to Swiss legislation. This would require efforts to cut the supply of recycled mercury, and to encourage permanent, environmentally friendly storage.

A consultation process on legal changes was launched last November and the government is set to publish its official position before the end of 2017.

Mercury is a highly toxic heavy metal considered by the World Health Organization to be one of the top ten chemicals of major public health concern.

The chemical element occurs naturally and can be released into the environment via the weathering of mercury-containing rocks, forest fires, volcanic eruptions or geothermal activities. But according to the United Nations, 90% of the 5,500-8,900 tons of mercury currently emitted or re-emitted each year to the atmosphere is man-made. It is released unintentionally from industrial processes such as coal-fired power stations, cement production, mining, waste incineration, and metallurgic activities.

Mercury is extensively used to extract gold from ore in artisanal and small-scale gold mining. It is contained in electrical switches, relays, measuring control equipment, fluorescent light bulbs, batteries and dental amalgam. Mercury is also used in laboratories, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, vaccines, paints and jewellery.

Stricter Swiss regulations

Campaigners say it is crucial Switzerland implements a full export ban for mercury and mercury compounds to avoid becoming a weak link in Europe; the European Union totally banned exports of mercury in 2011.

“If there is a partial ban, how can anybody control where mercury goes after? If it goes to another trader, it could again go to artisanal and small-scale gold mining, so it has to be a full ban,” said Elena Lymberidi-Settimo, European project manager with the Zero Mercury Campaign, an alliance of non-governmental organisations.

Franz Perrez, Head of the International Affairs Division at the Federal Environment Office, is sure that tough regulations will be introduced that ‘go beyond what Minamata says’.

“The trading of mercury will be more difficult under the convention,” he told swissinfo.ch. “Switzerland will follow the convention; it ratified it. Switzerland won’t continue to be a big exporter in the future.”

Nonetheless, strict implementation of the convention is disputed in Switzerland.

“The environment office wants an extensive ban on the export of mercury in the implementation regulations. It should only be possible to export research and analysis instruments in a controlled way and imports will be subject to authorisations,” said Rytz.

The office wants an export ban on batteries, switches, relays and dental amalgams containing mercury. It also calls for authorisation for imports of mercury compounds and alloys.

But economic lobby groups and the recycling firm Batrec Wimmis have contested the regulations, Rytz explained.

“It will be crucial to see whether the government weakens the regulations under pressure,” the Green parliamentarian added.

Future secretariat?

Strict guidelines on procedures for exporting mercury are expected to be adopted in Geneva. Another important issue still requiring global agreement is country reporting.

The Zero Mercury Working Group, an alliance of non-governmental organisations, says it is crucial to be able to collect national data on mercury production and trade.

“Countries will not have readily available information about production and trade in bordering countries or within their region, unless there is frequent reporting under the convention,” said David Lennett, Senior Attorney for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“Many borders between countries are porous and a significant portion of mercury trade is informal and illegal. Good data on legal trade flows will enable actions to address illegal trade, all of which has a huge impact on artisanal and small scale gold mining, the largest source of mercury pollution globally.”

The Swiss will also be watching closely for news on the future Minamata Convention secretariat.

Geneva is a centre of expertise for hazardous chemicals and waste. As home to the secretariats for the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POP), the Rotterdam Convention on the Prior Informed Consent Procedure for Certain Hazardous Chemicals and Pesticides in International Trade, and the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal, the city is keen to add the Minamata secretariat to its collection.

The Swiss say integrating the organisation into the current set-up would create synergies and reduce costs. A formal decision is expected this week.

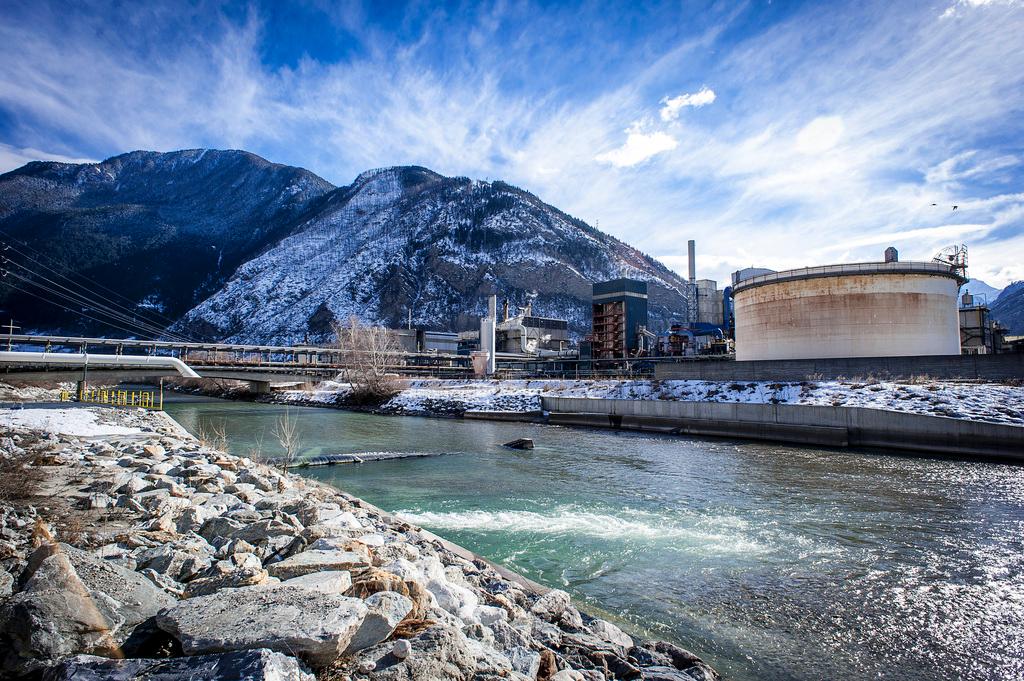

In the Swiss canton of Valais, it was revealed that mercury waste from the chemical company Lonza that was produced between 1930 and 1976 seeped into the ground around the town of Visp. Some 50 tons of mercury ended up in the local canal and accumulated in mud and sediment, which were spread on nearby farm land or used as embankments up until the 1990s. This was first uncovered in 2010.

In September 2017, it was agreed that private owners of polluted land should not pay for any clean-up measures. Canton Valais and the Visp and Rarogne communes will together pay a maximum of CHF3.5 million ($3.6 million) and any additional costs will be covered by Lonza. The first clean-up work is due to start this autumn.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.