New WHO scheme could speed response to global health crises

The Geneva-based World Health Organization (WHO) plans to launch a new system for sharing scientific research samples in the fight against Covid-19. We explain how this could work and what obstacles must be overcome.

“Sometimes viruses emerge in countries that have limited capacities to sequence and categorise them,” Sylvie Briand, director of the WHO’s Global Infectious Hazards Preparedness Department told swissinfo.ch. “If they are able to ship them to countries that have the latest technology and research capacities, this is good for the world, things go faster.”

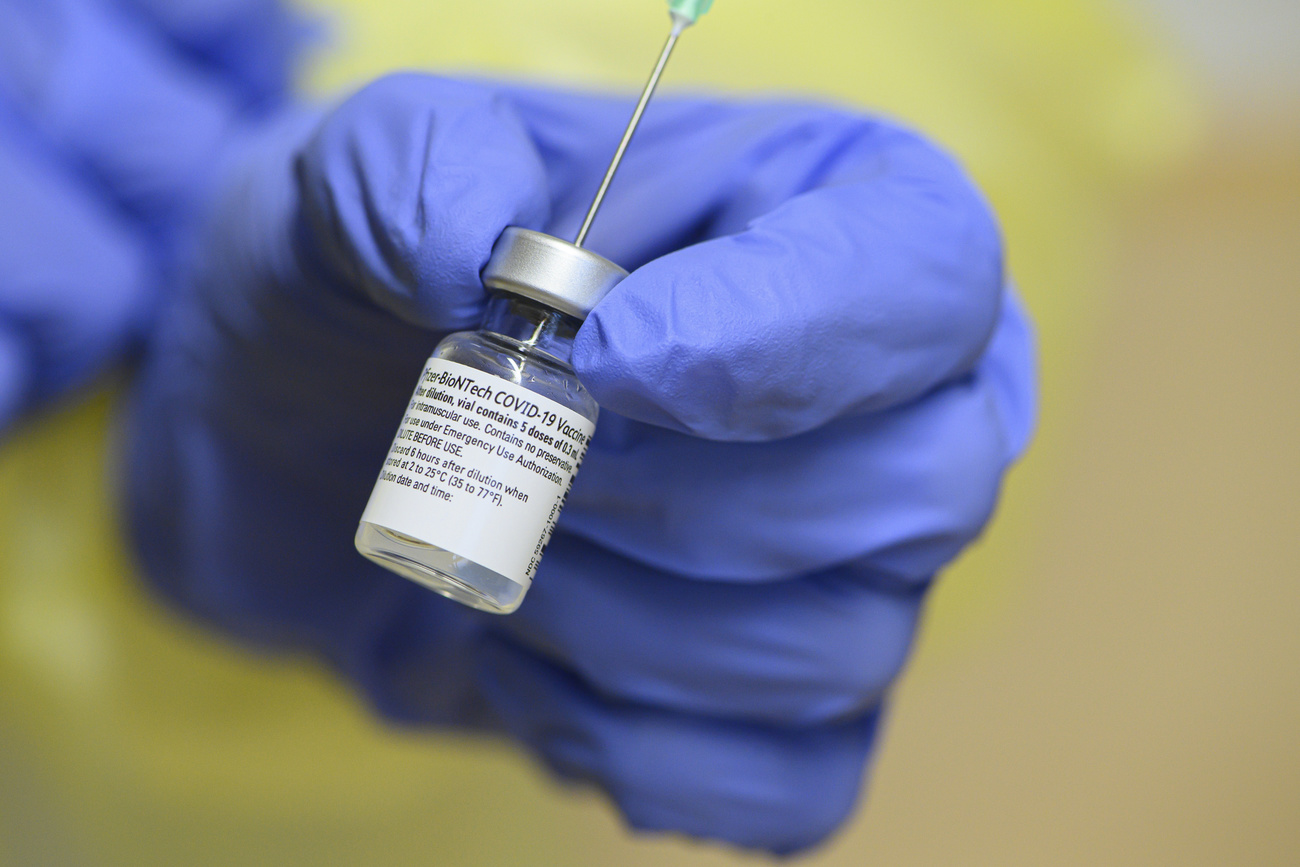

Vaccines, for example, might be developed more quickly for pathogens, which are the infectious biological agents causing disease or illness.

The new sharing scheme was first announced in November. The WHO director-general Tedros Ghebreyesus said the “globally agreed system for sharing pathogen materials and clinical samples, [would] facilitate the rapid development of medical countermeasures as global public goods”.

Ghebreyesus said this would be “a new approach that would include a repository for materials housed by WHO in a secure Swiss facility; an agreement that sharing materials into this repository is voluntary; that WHO can facilitate the transfer and use of the materials; and a set of criteria under which WHO would distribute them”.

WHO expert Briand says the health body has already allocated a team of staff to work on the project. She told swissinfo.ch that it would initially concentrate on Covid-19 but that the ambition was then to widen it to “emerging pathogens”. The WHO already has experience in this field, she said, notably with repositories for smallpox viruses and for influenza, adopted after the influenza pandemic of 2009, allowing a network for labs to exchange virus samples for research.

More

Swiss offer Geneva space for WHO pathogen exchange

Swiss government authorities did not wish to comment at this “very, very early stage” on Ghebreyesus’ statement that Switzerland had offered a secure lab to support the initiative. But an informed source confirmed talks were under way and that Switzerland is ready in principle to provide such space. “We are ready, but we are in discussions about what it would involve and what it would look like,” this source told swissinfo.ch.

A new system will also require new governance arrangements, according to a recent studyExternal link by the Geneva Graduate Institute’s Global Health CentreExternal link, to ensure the “rapid, fair international sharing of pathogen-samples…before the next major outbreak strikes”.

Lack of standards

“International access to samples is critical to understand pathogens and develop drugs and vaccines to control them but ensuring equitable benefit-sharing with source countries has proven difficult,” the study authors said. “This issue has raised growing attention and concern with recent outbreaks (Ebola, Zika, MERS and SARS-CoV-2 [Covid-19]), but the international system to address it remains wholly inadequate.”

Suerie Moon, Global Health Centre co-director and co-coordinator of the study, thinks the WHO initiative could be important. “In the absence of rules, such a biobank could be a step towards an international framework,” she told swissinfo.ch. “It’s not enough, because it needs diplomats to come together. But it could be a catalyst.”

Benefit sharing

The Graduate Institute report stresses the importance of sharing benefits, such as vaccines and medicines, as well as lab samples for scientific research to make them possible. “Will scientists continue to freely share if they don’t believe they are treated fairly in terms of benefits?” she asks. “I fear not, and the system would break down.”

She cites the example of Chinese scientists who shared genome sequencing data online in the early stages of the Covid-19 outbreak in China. This, she says, allowed the start of vaccine development notably by PfizerBioNTech, whose vaccine has already been approved and is being rolled out in some countries. But it’s unlikely the scientists who originally shared the data will also share the huge benefits, notably financial, of the vaccine.

Developing countries also tend to lose out, especially during disease outbreaks. The Graduate Institute report, for example, cites one person interviewed for its study as saying: “Developing countries are in general the weaker link of the chain when it comes to bilateral negotiations. So, if you’re having an outbreak and you need a medicine or some kind of therapeutic, and your population is rioting in the streets against you, you just say ‘please, help me’ (…) and then people say, ‘Okay, I’ll help you, but you will not have access, you will not have royalties’. You say okay.”

Moon points to “vaccine nationalism” during the current pandemic, with richer countries scrambling for bilateral deals with pharmaceutical companies. The WHO’s COVAX vaccine sharing scheme is currently the “only show on the road” to try and ensure that developing countries are not left out. She thinks the WHO would also be well placed to help improve fair pathogen and benefit sharing. “The WHO is definitely well-positioned to bring key players together, because it has done it before” with its Pandemic Influenza PreparednessExternal link (PIP) Framework in 2011. One of the key principles included in this long-negotiated framework is that pathogen and benefit sharing should be on an equal footing, that “everyone has valid concerns”, says Moon.

Swiss safe lab

She also thinks that Switzerland would be an appropriate country to provide the safe space for a new WHO biobank, because it is a neutral country, a “trusted middle power”, has a highly developed research and scientific infrastructure and is also the host country of the WHO.

But Switzerland has only a limited number of Level 4 (high security) labs that could store such pathogens, according to our information. Level 4 sites would be necessary, as most of these samples are dangerous.

Swiss capacity includes a lab at the Geneva University Hospitals (HUG) initially developed for the Ebola virus, and a lab in Spiez, central Switzerland, as well as one in Zurich. The Spiez lab has the most storage capacity and the widest remit, which includes nuclear, chemical and biological samples.

According to our informed source, the Swiss contribution to this WHO scheme could involve one or more of these labs, depending on the needs and the outcome of talks.

The WHO’s Briand says the WHO approach is pragmatic and that it aims to start with something concrete, even if small, and then expand. The first priority is to secure a physical repository, hence the talks with Switzerland. These are complex, involving technical, logistical and also legal issues, so it will depend how much time this takes.

When he announced the initiative Ghebreyesus stressed that such a scheme was needed quickly. “We hope it will be a matter of months,” Briand said.

Global Health Centre co-director Suerie Moon also stresses the urgency. “We currently have no reliable system for pathogen and benefit sharing,” she says. “This makes the world more vulnerable for the next pandemic.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!