US-Russia summits then and now: High tensions, mixed results

Like the two previous encounters between American and Soviet leaders in Geneva in 1955 and 1985, the upcoming summit between Joe Biden and Vladimir Putin may simply serve to keep one important option open: diplomacy.

This week’s summit is, in the words of the White House, an attempt to restore “predictability and stability” in relations between Russians and Americans, with tensions at a level not seen since the Cold War, some experts say. Russian meddling in the 2016 US elections, cyberattacks such as last year’s SolarWinds hack in the US, and the jailing of opposition figures by Russian authorities have deepened divisions between the two sides.

But the most pressing issue they will likely address is European security. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 really soured the country’s relations with the West. Its military build-up along the Ukrainian border three months ago was seen by the US and its European allies as a provocation and proof of Russian aggression in the region.

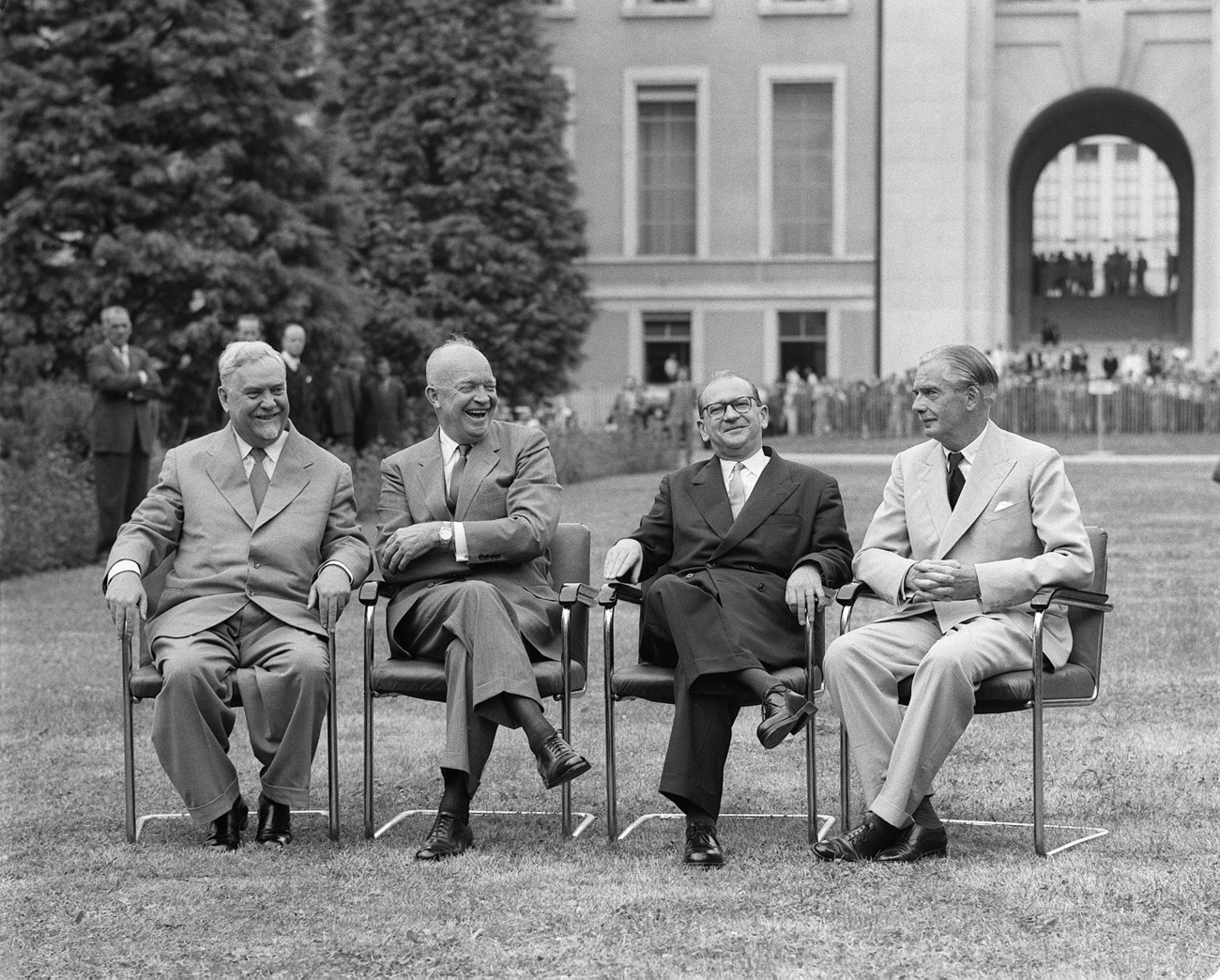

The two sides have been here before. When the US, the Soviet Union, Great Britain and France met for their first post-war Four Power Conference in Geneva in July 1955, European security was also top of the agenda. West Germany had just joined the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation – the military alliance created just a few years earlier to, among other things, repel Soviet expansionism – despite a campaign of threats by the Soviet regime.

The NATO problem

“There was a lot of tension across Europe because of [West German NATO membership],” said Jussi Hanhimaki, a professor of international history and politics at the Graduate Institute in Geneva. The Soviet response to NATO had come in May 1955, in the form of an Eastern mutual-assistance treaty, the Warsaw Pact.

But while the Pact died with the fall of the Soviet Union, since the end of the Cold War NATO has welcomed previous communist countries in central and eastern Europe, explicitly excluding Russia.

“NATO enlargement means that Russia is surrounded,” said Hanhimaki, and it explains some of the Kremlin’s foreign policy moves, including its annexation of Crimea and its “bullying” of neighbouring countries.

More

Newsletters

These days talk of Ukraine and Georgia joining the transatlantic alliance is a sore point in relations between the West and Russia.

“They are the crown jewels of the former empire – the red line that the West would cross in Russia’s eyes [if they joined NATO],” said Henrik Larsen, a senior researcher at the Centre for Security Studies at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich.

Open doors and ‘open skies’

Back in 1955, there was hope that disagreements between East and West could be overcome. With Stalin’s death in 1953, diplomacy to attenuate Cold War tensions had suddenly seemed possible.

Although the Soviets agreed to a text on German reunification that even made reference to free elections, the Geneva summit did not resolve the issue. The inclusion of West Germany in NATO continued to be a stumbling block. Subsequent events, like the Suez Crisis and Soviet intervention in the Hungarian uprising just a year later, further dampened any hope of “peaceful co-existence”, a term the Soviets had just gotten around to using, according to Hanhimaki.

Instead, the result of the summit, the Cold War expert said, was really to open the door to regular meetings between the two sides: “Diplomacy was not being abandoned, which was a concern in earlier stages of the Cold War.”

The summit is also notable for having set the stage for the concept of “open skies”, which US President Dwight D. Eisenhower brought to the table. Although his Soviet counterpart, Nikita Khrushchev, rejected the idea of an agreement to allow mutual aerial surveillance of their military installations, US President George Bush revived it in the late 1980s. The result is the 1992 Open Skies Treaty, a trust-building pact that has been ratified by the US, Russia and over 30 other countries and “an important détente agreement that marked the end of the Cold War,” as Larsen put it.

Arms control

By 1985, when leaders met again in Geneva, the focus had shifted to nuclear proliferation. The US and the Soviet Union were at that point the two main players, due to the size of their arsenal.

“On one hand, [the arms race] perpetuated conflict between the two, this knife-edge sentiment [of war], but at the same time it forced them to engage regularly to limit the potential of nuclear war,” said Hanhimaki.

Indeed, the Americans and Soviets met several times before the eyes of the world turned to Mikhail Gorbachev and Ronald Reagan in November 1985. Gorbachev, a newly minted head of the Soviet communist party, was “open to public diplomacy”, according to Hanhimaki. For his part, Reagan, though a staunch anti-communist, was willing to sit down to avoid nuclear war, which he saw as the biggest threat facing the world.

More

Diplomatic back channels: when Reagan and Gorbachev met in Geneva

“As in 1955, they don’t really agree on anything, except for continuing to have high-level contacts and to see each other again,” said the professor. The 1985 summit opened the door to serious negotiations between the two superpowers to cut their nuclear arsenal just half a decade before the Cold War finally ended.

If arms control remains on the agenda in 2021, it’s because Russia and the US still have among the biggest weapons arsenals in the world – an issue that continues to force them to sit down, according to Hanhimaki. At the summit Biden is likely to work on what Larsen calls “local warming” – strategic stability and risk reduction by enhancing existing agreements in order to prevent the two countries from “stumbling into war”.

One agreement they won’t be building on is the Open Skies Treaty. Just days after announcing the 2021 Geneva summit, the US said it would not rejoin the pact – following a withdrawal in 2020 by the previous administration – due to Russian violations of the terms. Russia too has since said it will abandon the treaty.

China in the background

Security aside, the summit will be equally about optics, “meeting in order to be seen to be meeting,” said Hanhimaki.

Larsen agrees: “Biden wants to show distance from [his predecessor, Donald] Trump, who showed little interest in international leadership.”

Prior to coming to Geneva, the president will have met with G7 countries and NATO allies in the United Kingdom and Brussels – a direct signal to Putin that Biden is “the leader of the free world”, in Larsen’s words.

Human rights will be on the Geneva agenda. But the goal will not be to change the Kremlin’s behaviour – “Putin is not going to release [opposition figure Alexei] Navalny from prison,” Larsen pointed out – but to show a domestic audience and US allies that he is addressing the issue.

As for Putin, Larsen said, “a Russian leader would never miss a chance to meet with the US president – it’s a prestige thing, to show that they are on the same level”, even if economically and in terms of global leadership, this is not the case. Getting a chance to play up tensions between the two countries works in Putin’s favour domestically, Hanhimaki agreed.

Today the biggest rival to the US is China, and Biden himself has said that the summit will show the East Asian power that the US is back on the international stage.

More

What Switzerland can do about the US-China rivalry

Analysts believe that one of Biden’s chief aims on his Europe trip will be to rally Western democracies in its competition with China. But although China has talked up its good relations with Russia, Larsen says the two are not allies and Russia would have no interest in drawing closer to China – or the West.

“There are areas where [Russia and China] don’t align,” said the researcher. “There’s no natural trust between them.”

Instead, Larsen speculates that Biden will want to define a “living arrangement” between Russia and the West: “Maybe Biden can convince Putin to scale down cyberattacks and election meddling in the US and other democratic countries”, in exchange for a promise to reduce existing sanctions against Russia, for example. But Putin, according to Hanhimaki, will resist giving away too much for fear of undermining his hold on power at home.

However, the main bone of contention – the sabre-rattling on the Ukraine border – is likely to remain unresolved for the foreseeable future, both Larsen and Hanhimaki said. Like in 1955 and 1985, the summit may at most help to keep communication channels open.

“They will maintain a civil discourse as much as possible that maybe overtime, could have an impact in making the relationship at least appear more civil,” said Hanhimaki.

More

The changing face of International Geneva

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.