‘The heroin programme is a kind of prestige project’

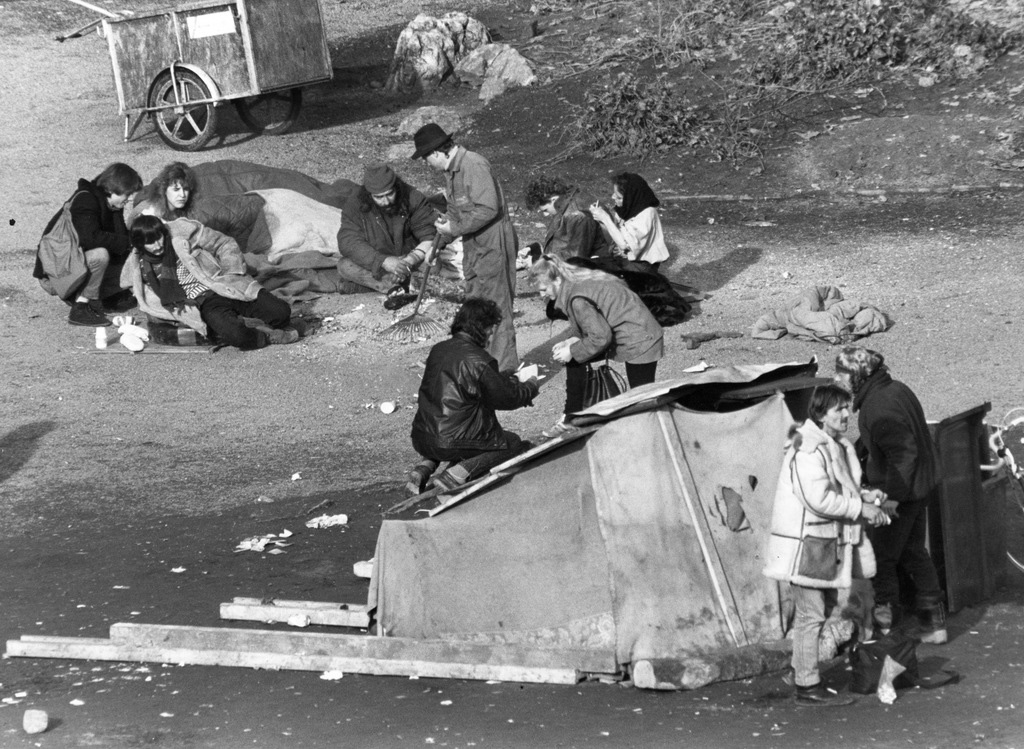

At the beginning of the 1990s, pictures of the open drug scene at the so-called "Needle Park" in Zurich went around the world, leading to the introduction of heroin prescription. Strongly criticised at first, it has since been hailed as an example.

Doctor André Seidenberg, who has treated 3,500 patients suffering from addictions in his career, was one of the first to provide emergency help in Needle Park and to call for clean syringes to be given out to addicts. Police and the justice authorities tried to deal with the problem with repressive measures that failed to work. The crackdown even encouraged drug addiction and the drug trade, Seidenberg claims.

swissinfo.ch: Twenty years ago Switzerland became the first country to prescribe heroin to therapy-resistant addicts. Has it been a success story?

André Seidenberg: Yes, although you have to bear in mind that the heroin programme has been marginal and to my knowledge never reached more than 5% of the affected people. It is a kind of show project, a prestige project.

It is however a success because in Switzerland, the majority of people dependent on opioids are in treatment, mostly with methadone, and a small proportion, particularly those who respond poorly to therapy, with heroin. It would be preferable if the proportion of addicts in treatment could be increased. I wish we could have gone further with the medicalisation and legalisation of the market.

More

Zurich’s infamous Needle Park

swissinfo.ch: Would that have had an effect on the black market?

A.S.: Of course. The black market is a market that is encouraged by repressive measures and ultimately produces poor products that are harmful to people. I wish we could have a less hypocritical approach to drugs.

swissinfo.ch: Then you are in favour of a general legalisation of drugs?

A.S.: I am in favour of better market control. It is an international problem, because we still have a very active drug wars in many regions.

Appropriate control of the drug market is not a trivial matter either. One cannot for example just legalise cocaine and think that all problems will be swept away. It would have to be introduced very carefully.

Since 1991 Switzerland has implemented the so-called four pillar policy of prevention, therapy, damage limitation and repression.

This pragmatic policy was developed largely in response to the extreme drug-related misery in Zurich in the 1980s and 1990s.

The controlled prescription of heroin was first introduced in 1994.

In 1997, the Zurich Institute for Addiction Research came to the conclusion that the pilot project should be continued because the health and living situation of the patients had improved. There had also been a reduction in crime.

In 1997 the people’s initiative ‘Youth without Drugs‘, which called for a restrictive drugs policy, was rejected by 70% of voters.

In 1998 74% of voters rejected the ‘Dro-Leg’ initiative for the legalisation of drugs.

In 2008 68% of voters accepted revised drugs legislation. Since then controlled heroin distribution has been anchored in law.

The new law came into force in 2010.

swissinfo.ch: How is life different for a person who doesn’t have to seek out heroin in the backstreets anymore but receives it regularly as a medicine?

A.S.: A person who receives their fix twice a day is in psychologically better condition, is more stable in every way. Of course there are side effects and even lasting impairments. Those who take this substance daily suffer from decreased libido, sleep problems or a limited capacity to experience emotional states in between euphoria and sadness.

People who take part in a heroin programme are also freed from the necessity to finance their existence through illegal activities. Delinquency, prostitution and social deviances of all kinds have decreased.

swissinfo.ch: So they can lead a normal life?

A.S.: The possibility of procuring drugs in this [legal] way makes a big difference, because in illegally procured drugs tend to be consumed in more dangerous ways. Most addicts are not in a position to always inject themselves carefully, which can lead to infections and infectious diseases. Overdoses also happen much more easily with drugs bought on the street.

When we are able to look after people medically, these risks are avoided to a larger extent. With controlled distribution people are able to lead a mostly normal life, although there are more people getting disability benefit among those taking part in the heroin programme, compared to the methadone programme.

swissinfo.ch: So from a medical point of view the focus is on limiting harm and stability rather than abstinence?

A.S.: The priority for doctors is to avoid serious harm to the body and death. Healing the soul comes, in medical terms, just after the body.

swissinfo.ch: Should abstinence not be the goal of a state drugs policy?

A.S.: That was the goal of politicians and society, and many doctors still nurture this illusion. But it’s a very dangerous strategy. Heroin addiction is a chronic illness. Only a small, shrinking minority of opioid addicts will become abstinent long-term. And most of them suffer during their abstinence.

With heroin – as opposed to alcohol – abstinence doesn’t improve well-being and health. The death rate is three to four times higher for abstinent patients, compared to those prescribed heroin or methadone. Repeated attempts to come off the drugs can trigger psychological difficulties, that can then lead to self-harm.

More

‘Without the heroin programme I’d probably be dead’

swissinfo.ch: Is heroin still an issue today?

A.S.: Thankfully we rarely see young people taking up heroin. Consumption has fallen massively. One per cent of those born in 1968, the Needle Park generation, became addicted and many of them died because of their addiction or are largely still dependent.

The average age of a heroin addict in Switzerland is now around 40. If we hadn’t stopped this development at the beginning of the 1990s, young people born in the following years would have been affected to the same extent. There are societies, for example the countries of the former Soviet Union or Iran, where a significant percentage of the population is dependent on opioids.

swissinfo.ch: You tried out various drugs, including heroin. Why didn’t you become addicted?

A.S.: Maybe I was just lucky. When I was young I tried out almost all kinds of drugs. I was able to satisfy my curiosity and maybe also learnt certain things that could be useful for my patients. I also got to know the danger of drugs: I lost many friends, even before my medical studies began.

swissinfo.ch: Do you have to have taken drugs to be a good drugs doctor?

A.S.: No, I would not recommend that. When dealing with problems that have to do with the psyche, it is definitely helpful to have an open mind. But you don’t have to try out everything for that, because that could be harmful and dangerous.

(Translated from German by Clare O’Dea)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.