The power of lobbies in Heidiland

Switzerland has one of the most highly-developed systems of democracy in the world. But the influence of pressure groups on political life is hardly regulated and politicians are concerned that private business is getting too cosy with parliament.

“There are too many parliamentarians representing very specific economic interests, instead of supporting values or the public interest,” complains the young centre-right Radical parliamentarian Andrea Caroni, who was elected in 2011.

“Some of them are ready to vote for just about anything. They’ll sell their grandmothers, if they can only get votes in exchange when their particular interests are at stake.”

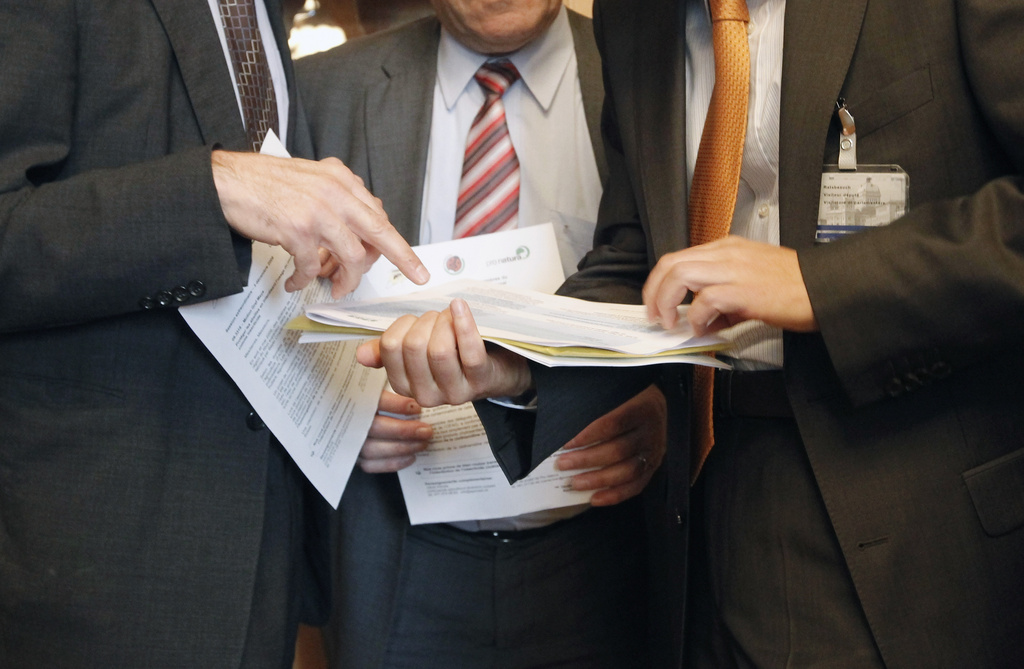

The economic might of lobbies is on show regularly in the Swiss parliament. Whenever the two houses are required to make decisions on matters regarding banks, insurance companies, health insurers, the energy sector or agribusiness, representatives of those interest groups take turns at the microphone to make their pitch (see infobox).

For Chiara Simoneschi-Cortesi of the centre-right Christian Democrats, who gave up her seat in 2011, “one of the most scandalous things in parliament was to see colleagues getting up to speak and reading prepared statements from their lobbies, often without even understanding them”.

The price of these close ties between some parliamentarians and business lobbies could be the large sections of the population whose interests are underrepresented – consumers, insurance holders or patients.

More

Do special interest groups threaten democracy?

Part and parcel of democracy

However, lobbies – including business lobbies – play a vital one in the consensus-based Swiss democratic system. Before being put to a vote in parliament, every major bill is subject to a consultation process, in which all interested parties are supposed to have their say.

“Lobbies are part and parcel of our democracy.” says Fritz Sager, a lecturer in political science at the University of Bern. “Our system is designed to have issues put to a referendum only as a last resort.”

“So when a piece of legislation is being developed, an attempt is made to hear from all the parties involved and to take into account all the interests at stake. Lobbying can be considered as one way to make sure we include all the interests and all the information that will lead to a decision supported by the widest majority.”

For Sager, the role of lobbies is also justified by the fact that Switzerland has a parliament in which most members are not fulltime politicians.

“Parliamentarians can’t be expected to have a detailed knowledge of every issue. They need information, some of which they get from their parties, but also from lobbyists. In that sense, lobbying is a thoroughly legitimate activity, a part of the system.”

The Swiss parliament is made up of two chambers: the House of Representatives with 200 seats, and the Senate representing the cantons, with 46 seats.

Generally, they meet only four times a year, in regular sessions of three weeks.

Switzerland has a part-time parliament, since members usually hold down regular jobs besides their political activity.

Many parliamentarians are involved in private industry: they support the interests of companies they work for, sit on corporate boards or are entrepreneurs. However, a certin number also work for unions or other associations, providing a counterweight to business interests.

Members of both houses have been required for some years now to report their outside activities to the federal chancellery, but there are no systematic checks.

No need?

Sager admits that lobbying conveys a rather negative image, but thinks this is mainly due to the lack of transparency about relations between lobbies and members of parliament.

So far almost all attempts – coming mainly from the Left – to regulate and control lobbying have failed. Parliamentarians have only in the past few years been required to declare their interests in companies, industry umbrella groups, associations and other groups.

But both chambers of parliament have rejected calls for transparency on parliamentarians’ income and party funding. The prevailing view is that honesty is the rule and there is no need for background checks on individuals or party activities.

“Overall, one gets the impression that the political process here still functions rather well and that there are enough corrective mechanisms to prevent major abuse,” says Felix Uhlmann, who teaches government law at the University of Zurich.

“But maybe this is just an illusion – we think we live in Heidiland and we don’t want to see the real problems.”

The influence of lobbies in the Swiss political system is particularly evident in the field of health insurance. Almost all members of the health committees in both chambers are linked to health insurers, pharmaceutical companies, hospitals, medical associations or patient groups.

The divergent interests represented in parliament have blocked reform of the health insurance system for years, while health insurance premiums go up annually.

The influence of lobbies has also bogged down legislation on cartels and parallel imports, whereas parliamentarians have been fairly quick to respond to demands from banks, insurers and pension funds.

Apart from campaigning for legislation favourable to their interests and avoiding adverse legislation, lobbies seek to influence parliament to get grants and tax breaks for their constituencies.

In fact, according to a study by the federal government, tax breaks reduce the revenue flowing into state coffers every year by CHF17 bilion to CHF21 billion.

Regulation

Unlike in Switzerland, other European countries as well as the EU Commission and European Parliament have recently introduced measures to curb lobbying: they range from registering lobbyists to codes of conduct and rules on the funding of political parties.

The toughest rules of all are currently to be found in the United States, where anyone carrying out lobbying activities has to register, state the source of their funding and even reveal their contacts with elected representatives and the administration.

Asked if the Swiss should be aiming for similar regulation, Uhlmann is sceptical.

“To regulate lobbying as they now do in the US requires a huge amount of work, a large regulatory apparatus and an effective system of control,” he swissinfo.ch. “There would have to be sweeping changes that are hard to imagine in Switzerland.”

Not everyone in parliament has lost hope of some change. Among them is Caroni, who has proposed an initiative to regulate lobbies, at least within parliament itself. Lobbyists wanting to get a foot in the door would have to be suitably accredited, declare their mandate and sign a code of conduct.

“I can’t shut down the lobbies and I don’t even want to, but I do want them to be subject to standards, at least in here, at the heart of our democratic system,” said Caroni. “That should help to counteract the image of too much cosiness between lobbyists and parliamentarians, who today often seem to the public like Siamese twins.”

Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.