Re-Telling Swiss history

Every Swiss knows that Switzerland was established in 1291, when the three founding fathers took an oath to defend their freedoms together against outside overlords.

They have their statue in the Swiss parliament, and every year on August 1, Swiss National Day, the alliance they sealed on the Rütli meadow on the shores of Lake Lucerne is celebrated with speeches and bonfires.

But suppose it wasn’t really like that? Recent historical research has struck a body blow at the heroic myths, and the new permanent exhibition at the Forum of Swiss History, in the central city of Schwyz, brings this revised picture vividly to life.

In a carefully guided circuit over three floors, the visitor learns about the European context from which Switzerland developed and why it took the form that it did.

Eye-catchers

Some of the items on display are strikingly beautiful, some are surprisingly well travelled, some are dramatic. All have been carefully chosen to illustrate a specific theme.

There is the artistically carved ivory hunting horn, for example, a symbol of the power of the Habsburg counts who had their original base in what is now canton Aargau – and whom traditional accounts have always cast in the role of villain, trying to stamp out the freedoms of the plucky Swiss.

There is the silk cope, woven in the Italian city of Lucca and which ended up in a monastery in the Swedish town of Uppsala, illustrating the importance of the trade routes over the Alps.

And then there is the dead cow, its throat cut, its blood seeping into the museum carpet, a demonstration of the lawlessness of feuding petty nobles and the havoc they wreaked on local communities.

All of them reflect in one way or another the influences that shaped the way Switzerland developed.

Setting the scene

The exhibition is called “Switzerland in the Making”, and looks at what was happening in the 12th to 14th centuries in that part of Europe known as the Holy Roman Empire, which stretched from Germany to northern Italy – and took in central Switzerland.

“The challenge was to narrate the emergence of Switzerland from a European perspective, but that was really important us: to show things from an unfamiliar point of view,” curator Pia Schubiger told swissinfo.ch.

The imaginatively designed exhibition is divided into a series of displays, each containing a scene-setting background, an interactive element, and a single illustrative item.

Visitors can listen to the voices speaking different languages in the scriptorium, where monks copied manuscripts; they can feel for themselves what it was like to slog over the mountains, walking on a step machine as they watch a film of the Splügen Pass; children can even dress up in mediaeval costume and mail a photo of themselves to their friends.

The items come from different European collections: none are on permanent display. Not only are many too fragile to withstand lengthy exposure, but changing the exhibits also means visitors will have a reason to come back.

A European context

The top floor of the exhibition focuses on the general European context: the power relations in the empire, the growth of literacy and the adoption of Indo-Arabic numerals – starting in Italy – which revolutionised trading practices.

The Habsburgs with their hunting horn were just one of many noble families who held extensive lands in exchange for the military service they owed to the emperor, in a system where rights and duties were handed down from emperor to the high nobility to knights – and which became increasingly shaky as society grew more complex.

The visitor then goes down one floor to focus more closely on the alpine area, and the development of long distance trade networks – like the one that took the cope from Italy to Sweden. Not only merchants, but soldiers, pilgrims and muleteers travelled between the different areas of Europe, spreading news and ideas.

Thanks to this interchange, people living north of the Alps knew what was happening in Italy, where many cities had persuaded the distant emperor to grant them a large degree of autonomy, including the right to pass their own laws and levy their own taxes.

Why Switzerland?

Such autonomy was attractive to the neglected rural areas of central Switzerland too, where there were few powerful lords interested in keeping order for the sake of general prosperity and where communities, led by wealthy peasants, therefore started to take over this duty for themselves.

And the dead cow on the last floor, ushering the visitor into the area that focuses on the emergence of Switzerland, shows how urgent it was to stop the feuding of petty nobles, a serious obstacle to agriculture and trade.

That was the context in which the Rütli oath was sworn. Autonomous communities were obviously stronger if they banded together. The oath taken by the “forest cantons” of Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden was by no means exceptional at the time: many Swiss and European cities formed similar leagues, although most were only temporary.

But what about William Tell? What about the hero Winkelried, who famously sacrificed himself at the battle of Sempach in 1386 to enable the Swiss troops to break the Habsburg ranks and sweep to victory?

They are there, certainly, but at the very end, set firmly in the context of mythology. The first written accounts of the foundation of the Swiss Confederation emerged in the 15th century, and were clearly aimed at strengthening the bonds of the still loose alliances.

How better than to depict the birth of the country as a heroic struggle against aristocratic oppression?

But the point of the exhibition is to show people that what they probably learnt in school has been seriously challenged. So Schubiger isn’t worried about their reactions.

“I think that if we explain the story well to visitors, it will be an eye-opener for them and they will be glad to get a new way of seeing things.”

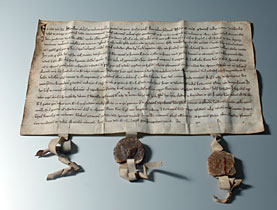

In the traditional accounts, three founding fathers, representing the cantons of Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden swore an oath of mutual support in 1291.

They wanted to stop the emperor imposing an outside governor to administer their affairs.

The 1291 document was not unique; it refers to an older alliance that has not been traced. It was forgotten until the late 19th century; until then an alliance of 1315 was regarded as the founding act.

William Tell, a skilled crossbowman from the Uri village of Bürglen, is supposed to have defied the wicked Austrian governor Gessler.

He ignored an order to salute Gessler’s hat, which had been stuck on a pole.

Gessler then ordered him to shoot an arrow off his son’s head.

Although Tell performed this feat, Gessler arrested him.

Tell escaped from the boat taking him to prison when a storm blew up on Lake Lucerne, then ran ahead and killed Gessler as he rode to his castle.

The story of the apple is found in Scandinavia; no governor named Gessler has been traced.

Tell’s story was popularised in particular by the German writer Friedrich Schiller in 1804.

Arnold von Winkelried is said to have broken the enemy lines at Sempach in 1386, one of the battles that dealt a decisive blow to Habsburg claims in central Switzerland.

He threw himself on the enemy spears, clearing a way for the rest of the Swiss Confederate army.

The story was first mentioned in 1533.

The Forum of Swiss History in the central Swiss town of Schwyz is one of the three museums in the Swiss National Museum group.

The other two are the National Museum Zurich, and the Castle of Prangins in western Switzerland.

Their permanent exhibitions cover Swiss history from the beginnings to the present day, but each has a different focus.

The museum in Zurich covers four thematic areas: migration and settlement, religious and intellectual history, political history, and economic development.

Prangins, housed in a chateau built in 1730, focuses on life in Switzerland in the 18th and 19th century.

Schwyz covers the emergence of Switzerland in the 12th to 14th centuries.

Most of the information is presented in four languages, including English.

There are special guides aimed at children.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.