Researchers find clue to antibiotic resistance

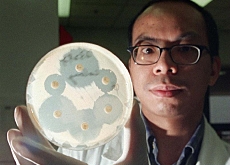

Scientists at Zurich University have for the first time mapped the inner workings of a so-called pump inside bacteria that is a natural defence against antibiotics.

The researchers say their findings could eventually lead to new ways of overcoming drug-resistant bacteria, but warn that it is not a solution by itself.

Bacteria resistant to drugs have become more widespread in recent years, especially in hospitals. This has been due mostly to continuous use of antibiotics and detergents in the clinical setting.

Resistant bacteria have become a real problem since antibiotics cannot be used against them, and a bacterial infection can be deadly for a patient with a depressed immune system.

Whenever antibiotics come into play, bacteria need to find a way to survive the attack. What usually happens is that naturally resistant strains survive and then flourish, often passing on genetic material to other bacteria.

Bacteria recognise antibiotics and – if resistant – implement strategies to fight them off.

“Antibiotics target processes inside the cell which are vital for its survival, such as DNA replication,” said Martin Pos, a physiologist at Zurich University. “If the bacteria recognises the antibiotic as it enters the cell, it can for example set up a pump in the membrane to expulse it.”

Pos and his colleagues, as well as researchers from Konstanz University in Germany, have shown how such a pump, located in the bacterial cell membrane might work.

“The antibiotics are squeezed through the pump starting from the inside of the bacteria to the outside,” he told swissinfo. “

Tunnel

The pump has been described as possessing a tunnel. It opens towards the inside of the bacteria seeking antibiotics and other harmful substances for the bacteria.

Once it has captured the antibiotic substance, it closes on the inner side and opens at the other end on the outside of the cell membrane, expulsing the intruder before starting the process over and over again. The bacteria are to all intents and purposes resistant.

According to Pos, it might be possible for the pharmaceutical industry to use this blueprint to find ways of inhibiting the pump mechanism. “If you could find a molecule that would bind to the pump and render it inactive, antibiotics could then enter the cell properly and kill it,” he added

He warns though that would probably take some time to accomplish with no guarantee that an inhibitor could be used successfully for treatment of bacterial infections.

Pos says that not all bacteria, especially multi-drug resistant ones, would be susceptible to being eliminated by this method.

Some like the opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which can cause severe infections, would probably respond to a potential inhibitor of the pump and therefore to antibiotics.

But others such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), usually found on the skin, wouldn’t.

“The problem with observed multi-drug resistance is that the pump is not the only defence mechanism for bacteria,” said Pos. “It often works in combination with other mechanisms for example with tools that cleave antibiotics, so there are multiple defence levels.”

“But if we can inhibit the pump in some cases, it might be enough to kill off the bacteria.”

The results of the study are published in Friday’s edition of Science magazine.

swissinfo, Scott Capper

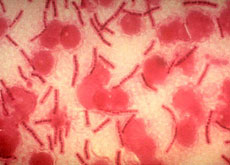

Antibiotic resistance occurs when bacteria change in some way that reduces or eliminates the effectiveness of drugs, chemicals, or other agents designed to cure or prevent infections. The bacteria survive and continue to multiply causing more harm.

When penicillin became widely available during the Second World War, the product of the soil mold Penicillium crippled many types of disease-causing bacteria.

But four years after mass production began in 1943, microbes began appearing that could resist it.

The first bug to battle penicillin was Staphylococcus aureus. This bacterium is often a harmless passenger in the human body, but it can cause illness, such as pneumonia or toxic shock syndrome, when it overgrows or produces a toxin.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.