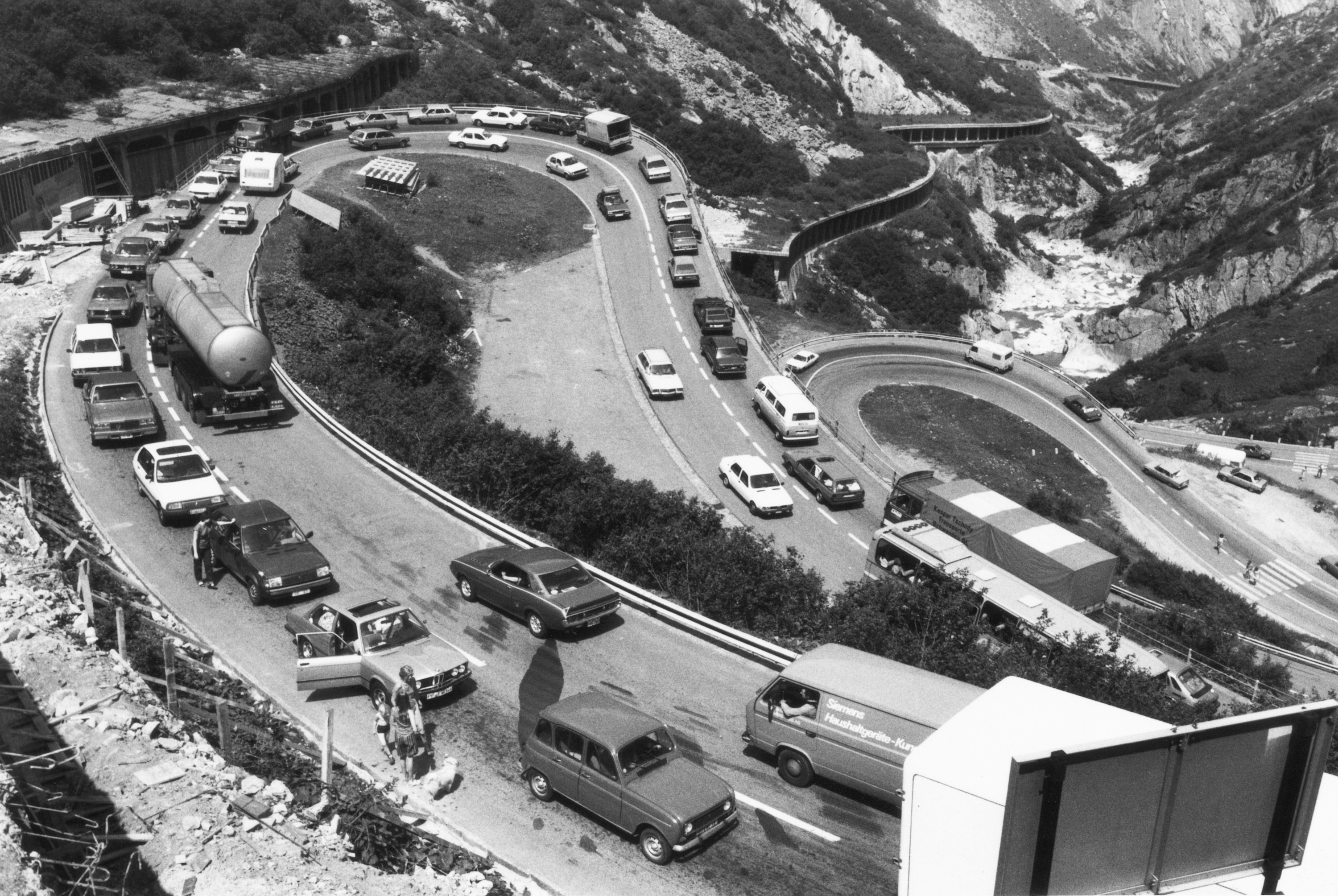

Truck drivers hit the rails and take a break

Instead of taking the motorway from Basel to Chiasso, every year 100,000 trucks cross Switzerland by train. On the “Rolling Highway” drivers from all over Europe spend the night in the same compartment. swissinfo.ch went along for the ride.

The railway workers in their orange overalls have an unenviable job. In the summer heat sweat is streaming down their grubby faces under protection helmets. The open area of the loading yard on the outskirts of Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany, offers little shade from the noonday sun, and lots of muscle is needed for the assembly of the mobile ramps on the last railway carriage.

On the tarmac next to the tracks 20 trucks are parked and ready. Most of the drivers have left their cabins. They have to walk over to the train booth to go through the transport formalities.

Many vehicles have east European number plates. But the registration is not a reliable guide as to where the goods and drivers come from.

Christian, who drives his truck first onto the weighing scales, is from Romania. Today he is transporting metal from Germany to Italy for an Austrian firm. The rolling highway takes 44 tonnes per truck, four more than is allowed on Swiss roads.

Yellow and red cards

“Forty-four-tonners are soon going to be more the rule than the exception,“ says Wolfgang Ziebold, responsible for the vehicle dimensions. The higher weight limits on the railway are a decisive advantage for some transporters.

In his right breast pocket Ziebold has a yellow card, in the left a red card. “Any driver in the world can understand this language.” He shows the yellow card when “for example, the antenna is still attached or the driver has to adjust the load”.

Mostly the driver can fix up the truck according to the regulations there and then. But it happens on one train in three that a driver gets a red card because the load is not secured, the tarpaulin is broken or the vehicle is too high.

The railway company doesn’t concern itself with fact that loads with these defects should not be allowed on the road either, because the same rules apply there. The offending drivers are not reported to the police.

“The drivers are responsible for their own trucks,” says Martin Weideli, head of production at RAlpin, the operating company of Rola (Rolling Highway) Switzerland.

Driving onto the loading ramps requires precision. There is only a few millimetres of space on each side of the trucks’ wheels. Despite the narrow margin, most lorries roll on easily in one go.

The drivers have to spend the nine-hour train journey in an accompanying carriage. Because the drivers have to take a break of exactly nine hours, as set down in the night and rest regulations, they are only permitted to return to their trucks in Novara, Italy. “That’s one of our best selling points,” Weideli adds.

Stiff competition, low wages

“You shouldn’t do your report in Freiburg but in Novara,“ a German driver comments. “The drivers’ toilets there are not fit for humans.” There has been no hot water in the showers for four weeks, “broken flushing tanks and shower, the toilets covered in sh***.”

Weideli has to step in and appease the drivers.

“We know about the problem.” Although a partner firm is responsible, RAlpin has pledged to sort out the facilities. “It will be sorted by the end of August,” Weideli promises.

The reason the German driver, who introduces himself as Hans-Peter Behrendt, still uses the Rola almost weekly is because it allows him to skip a night.

“When I come, like today, from the Ruhr region, I have to take a break somewhere in Switzerland, either in Erstfeld or past the Gotthard. I can’t get further than that in ten hours.”

In the hard fought transport market everything is a question of cost. There is overcapacity since the expansion of the European Union eastward.

“You only have to take a look at what is happening on the train,” he says hinting at his colleagues from eastern Europe who “drive for large haulage contractors from the west for low salaries”.

Fellow German Andreas Schäfer from Haselünne takes the train only when he has a dangerous load because he can’t to go through the Gotthard tunnel with that. Today he is transporting 22 tonnes of nitro-cellulose, a potentially explosive substance that he collected at Osnabrück at Hagedorn Chemie for delivery to Milan.

More comfort

In the brand new drivers’ carriage the air conditioning is working. It is nice and cool even though the train has been standing in the blazing sun.

Three drivers from the Italian transport firm Pigliacelli sit down at the long table next to the cooking corner and share a meal of melon, cheese and bread.

At the next table a Slavic language is being spoken. The driver from Croatia has been driving for the Austrian Berger Logistik firm for 15 years.

“A serious company, that doesn’t put any pressure on its drivers,“ he says.

“They understand that something can always go wrong somewhere on a long-distance trip to cause a delay.” Today he is transporting empties for the Italian mineral water producer San Pelligrino.

The Polish drivers of the Dutch firm Dasko have already withdrawn to a quiet section where drivers can sleep on fold-up beds.

They are in good form and very pleased with the comfort of the new carriage. That morning they picked up fresh meat at a factory in the Netherlands, that they are transporting to Modena, Italy.

They work abroad in three-week stints with two days off along the way. “Then we leave the truck in Holland, get the bus and drive home for a week to Poland.” The working conditions at Dasko are alright they say, “€1,600 to €1,700 (SFr1,922 to SFr2,042) per month”.

A Romanian driver complains that his Italian employers want to reduce his salary from €3,000 to €2,700. Later he admits that he has just worked 30 days straight without a break.

FF Rola Switzerland

Up to 11 trains with a maximum load of 21 trucks make the trip daily with the Rola (Rolling Highway) in both directions between Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany and Novara in Italy on the Lötschberg-Simplon line.

One train per day serves the Gotthard line from Basel to Chiasso and back, with a maximum 28 trucks per train.

Some 100,000 trucks per year are transported through the Swiss Alps. Virtually every truck approved on European roads can be transported by Rola.

The railway is particularly suitable for special goods such as chemical products, high-tech components, spare parts and perishable foods. This route can be used to circumvent the night and Sunday driving ban.

The journey lasts nine hours and counts as rest time for drivers.

One disadvantage of Rola is energy efficiency. In comparison to container transport it involves more empty weight and carries fewer goods per length of train.

Rola’s share of all the freight crossing the Alps is 4.7% (7% of railway freight).

63.9% of the goods which crossed the Alps in 2011 were transported by rail, the rest by road.

The Austrian Rola on the Brenner transported 2011 almost three times as many trucks as the Swiss but over a much shorter distance. The French Rola at Mont Cenis is a much smaller operation.

(Sources: RAlpin AG and Swiss Transport Ministry)

(Translated from German by Clare O’Dea)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.