How robots can change architecture

Among the Gantenbein vineyards near Fläsch in eastern Switzerland stands a striking piece of architecture – what looks from a distance like an enormous basket filled with grapes is a brick facade built entirely by robots. It could be the future of architecture.

It’s a concept promoted by Fabio Gramazio and Matthias Kohler. The duo founded the world’s first architectural robotic laboratory at the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETHZ) in 2005 and remain at the forefront of research into this field.

They have just published a book, The Robotic Touch – How Robots Change Architecture, which according to its blurb “introduces a radically new way of thinking about and materializing architecture”.

“The most important message is that robots will change architecture in a deep way, will affect the processes which are behind the construction of our built environment,” Gramazio told swissinfo.ch.

We are meeting at a scale-model exhibition of the duo’s work on the ETHZ’s Hönggerberg science campus, where the department is housed.

Gramazio and Kohler do not build robots themselves, but programme them to build products and environments that cannot be achieved by human hands, explained the professor, as we passed by the models of intricately-assembled walls and concrete meshes.

Wine and high-tech

The 2006 extension to the Gantenbein Winery, depicted in the exhibition, is a perfect example.

“We were lucky to have very extraordinary clients who were willing to take the risk [on building this],” Gramazio said, recalling the five-month deadline before the grapes had to be stored.

“Even though the construction industry is conservative and complex, there are certain occasions which allow you to bring things from the laboratory into reality in a quick way. People see it and say it’s not just a vision any more, it’s feasible and it’s working.”

Other fruits of their research have been seen at the 2008 International Architecture Biennale in Venice in form of a snake-like wall and in a 22-metre long brick structure in New York.

Flying robots

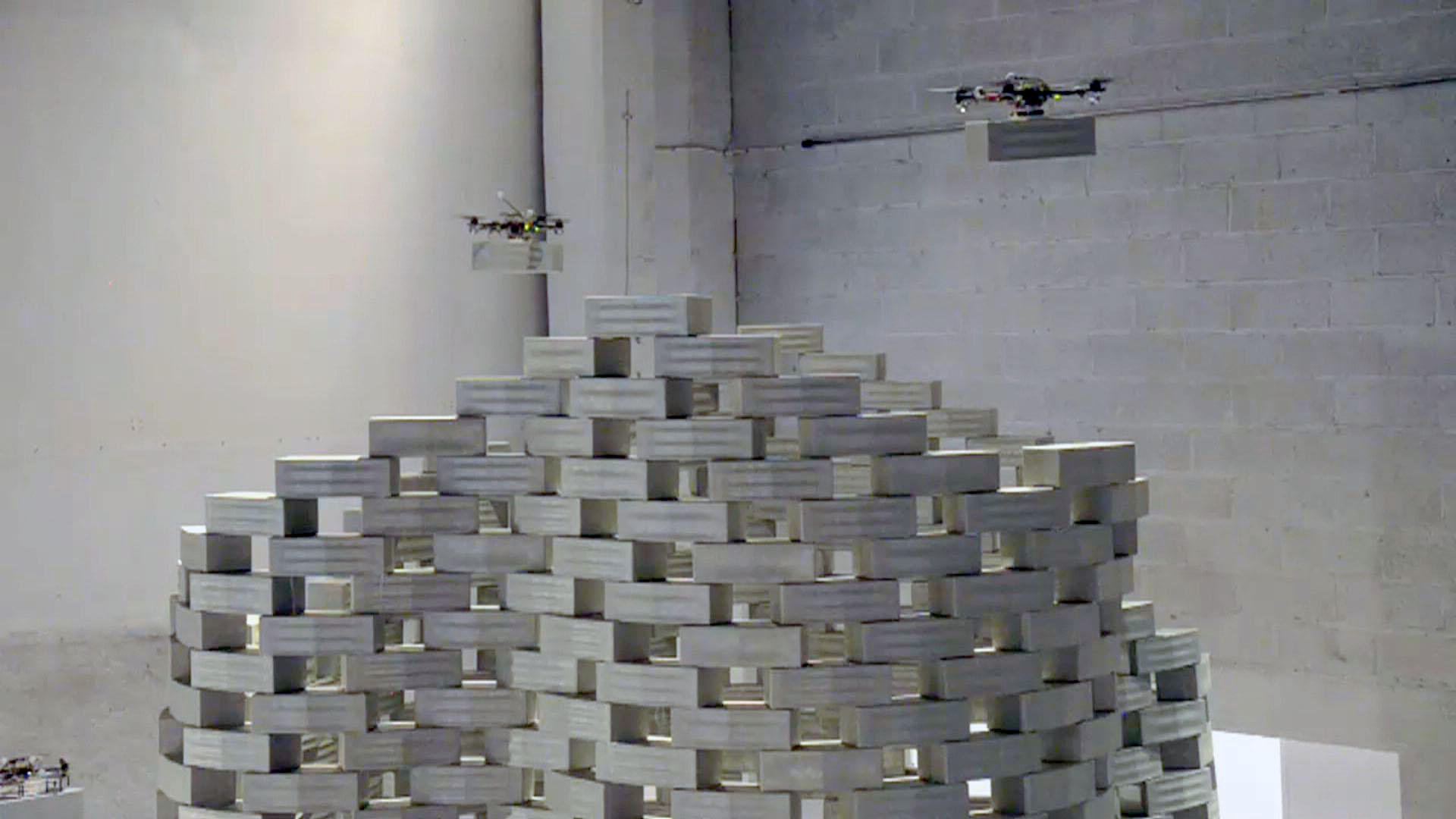

Particularly spectacular was the very first architectural installation to be assembled by flying robots at the FRAC Centre in Orléans, France.

More

Flight assembled architecture

The team is also exploring robotic fabrication in the design and construction of high-rise buildings at the Future Cities Laboratory in Singapore.

Closer to home, experiments are being carried out in the lab on the Zurich campus, with the aid of an orange industrial robot. A current project involves the robotic fabrication of complex concrete structures – until now not possible with conventional methods.

Robots have been around since the 1950s and some industries, such as the automotive sector, are now fully automated.

But the robot’s potential in architecture hasn’t yet been fully recognized, also because it is difficult to introduce them on building sites, said Gramazio, referring to, among others things, safety issues.

Complementary skills

There have also been fears that robots could put architects and builders out of business by taking over too many tasks.

But Gramazio and Kohler don’t see it like that, arguing that robots and humans bring skills that complement each other. This could lead to the reintroduction of the idea of craftsmanship that has become lost in the industrial age. Thus a person would not just monitor the machine doing its repetitive work but use his or her skills to inform the work of the machine, by inputting additional information.

Effectively, architects would have to be computer experts too. Gramazio and Kohler, who met as architecture students in the 1990s, developed an interest in programming as teenagers.

Feeling that designing and programming had many similarities – despite the perception that they were poles apart – the two started their own architecture practice in 2000 to “overcome this dichotomy”.

Pioneers

That the two are pioneers in the field of robotics and architecture is confirmed by their international colleagues, both of whom know the duo.

“They had a very good approach, doing aesthetically very good work,” Thomas Bock, Chair for Building Realisation and Robotics at the Technical University Munich in Germany, told swissinfo.ch.

“Gramazio and Kohler put robots and architecture on the map for many architecture faculties,” agreed Antoine Picon, professor of the History of Architecture and Technology at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Both professors said that the robots used by the duo could not normally be used for construction sites.

“If you use off-the-shelf industrial robots, like the ones used in the car industry, the robot will have a bad payload, be too heavy, and will not be weather, dust and dirt-proof. The design [of the site] should also be robot-orientated,” said Bock. “That’s also what I found out in 1984 when I tried the same approach in Japan, with an industrial robot.”

At the moment there are around 150 construction robots and around 30 automated construction sites in operation, mostly in Asia, using very different [more complex] machinery, he explained.

The future

Picon said Gramazio and Kohler’s use of robots raised a number of interesting questions about design. This includes forcing designers to think differently, which might be the most important consequence of the introduction of robots in architecture, at least for now, he said.

As for the future, Gramazio and Kohler’s next big plan is building a large timber roof structure on the ETHZ’s science campus itself.

It consists of more than 45,000 individual timber elements, to be woven into a complex, free form roof design.

“We are able to integrate running research into a large-scale prototype – it’s very exciting,” said Gramazio.

Gramazio and Kohler’s work at the ETH Future Cities lab in Singapore shows the duo’s wish to scale up their research and to investigate the impact of digital fabrication strategies on design for big buildings and cities, Gramazio said.

Singapore, as many Asian cities, has many high rises due to lack of space. The second wave of building needs to allow for further densification, while preserving the quality of life and allowing for a sustainable development, he added.

Manufacturing needs to be brought into the digital age.

“As such Singapore is an interesting living laboratory for our research, allowing for intellectual experiments which would feel somehow alien in Switzerland but are, in terms of global development, highly significant and prototypical for similar current and future developments in Asia at large,” said the professor.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.