Cancer blood test comes within reach

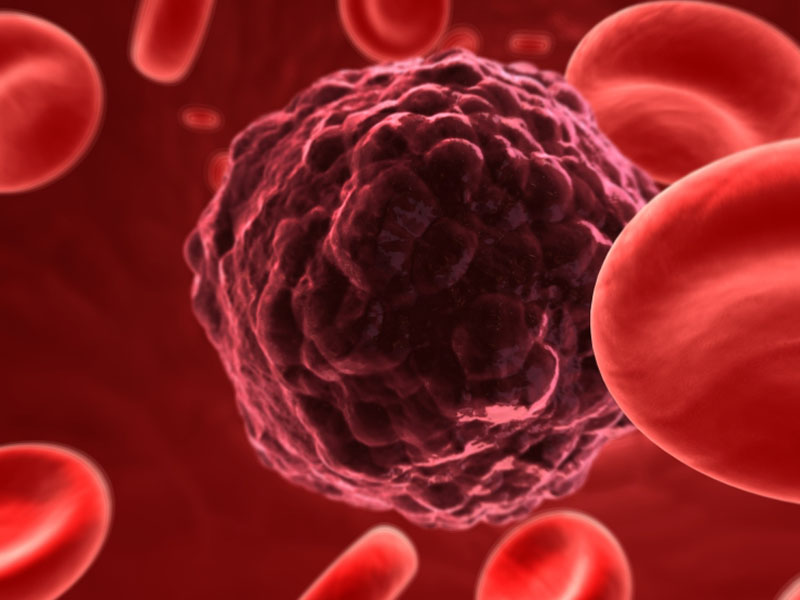

A test involving a small finger-prick of blood could in future diagnose types of cancer and help decide which treatment should be used, say Swiss scientists.

An interdisciplinary team has defined biomarkers in patients’ blood serum which indicate the presence of prostate cancer – the most common form of the disease among men in the western world. The method could be widened out to other tumours.

The work, by the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETHZ), the University Hospital Zurich and the Cantonal Hospital of St Gallen, is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal.

“The aim of the research was to define novel patterns, or signatures, in serum of patients that are able to report whether there’s cancer in the patient or not, in particular, prostate cancer,” Wilhelm Krek, from the Institute of Cell Biology at the ETHZ, told swissinfo.ch.

Current diagnosis methods which detect tumour antigens in the blood are not always reliable, often delivering false positives, the study authors say This is expensive and can lead to patients undergoing unnecessary biopsies.

Biomarker search

Scientists have been looking for biomarkers to identify cancer for many years. The concept is based on the idea that the onset of cancer triggered by a mutation, such as the inactivation of a tumour suppressor gene or the activation of an oncogene, is associated with a change in the surface protein pattern of cancer cells in the affected organ.

Since around 20 per cent of these surface proteins are potentially shed into the blood, it should be possible to detect these proteins in the blood serum.

Until now identifying particular biomarkers in the “big soup” of proteins in serum has been a big challenge, Krek says.

“There are other parameters that influence the pattern you are measuring, such as what you have just eaten.”

The team therefore took a targeted approach.“We focused on those surface proteins or fragments of them which appear on the surface when there is a specific mutation in a particular cell and that made a big difference,” the professor explained.

Mutated gene

The scientists looked at the tumour suppressor gene Pten, which is known to be mutated in around 50-60 per cent of human prostate cancers.

They first deleted the Pten gene from a mouse prostate. They then compared the surface prostate proteins in cancerous mice with the same proteins in healthy mice.

“That allowed us to extract a specific signature on the surface that was directly linked to the presence of the genetic alteration in that cancer cell,” Krek said.

The next key step was to see if the mouse model accurately reflected the pathology in humans which involved collecting serum and tissue samples from patients and a control group.

In all, 39 proteins were identified that indicated prostate cancer and computer models whittled this down to the four most reliable ones for a diagnosis.

“We then used this biomarker pattern to examine a cohort of patients whose blood had never been previously analysed. We were able to predict with precision, stability and reproducibility whether they were suffering from prostate cancer,” Krek said.

Personalised medicine

This precise method could offer hope to sufferers of the disease; more than 5,000 new cases are diagnosed in Switzerland each year.

The biomarker signature still needs to be validated in a large clinical trial, says Krek, but a start-up company, an ETHZ spin-off, is currently developing a diagnostic kit for prostate cancer. This will take a few years to come to market.

The professor hopes that the biomarker method could offer early diagnosis in cancers with the same gene mutation, such as womb and breast tumours.

In addition, the test contains information about the type of tumour, so could help define the most suitable treatment for the patient.

“We are going in the direction of personalised medicine based on specific cancer gene mutations,” Krek said.

Tumours are the second cause of death in Switzerland. In total 16,000 people die of cancer every year, according the Federal Statistics Office. 30% of men and 23% of women die of cancer-related deaths.

Actual deaths from skin and prostate cancer are slightly higher, while the number of fatal cases of breast cancer is lower compared with the average of 40 European countries, according to recent statistics.

Prostate cancer is the most common among men, at 29.6% of all male cancers. It has the second highest mortality rate, after lung cancer. There are 5,774 new cases of prostate cancer a year in Switzerland and 1,286 deaths.

Source: Swiss Cancer League, Federal Statistics Office

Cancer genetics-guided discovery of serum biomarker signatures for diagnosis and prognosis of prostate cancer was published in the prestigious PNAS journal.

It was published online on the PNAS website in February.

A team of biologists, clinical oncologists, pathologists and information scientists were involved in the interdisciplinary research.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.