Stemming the academic brain drain

Immunologist Salomé LeibundGut-Landmann says she has two families: her two small children and her lab team. She has made a success of academia, at an age when many of her peers have left it all together.

Her six-year-professorshipExternal link from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) has given her the chance to gain research independence and the means to build up her own team. It is normally awarded to post-doctorate researchers in their 30s, as a way of boosting their academic career. LeibundGut-LandmannExternal link has had her funding for 5.5 years.

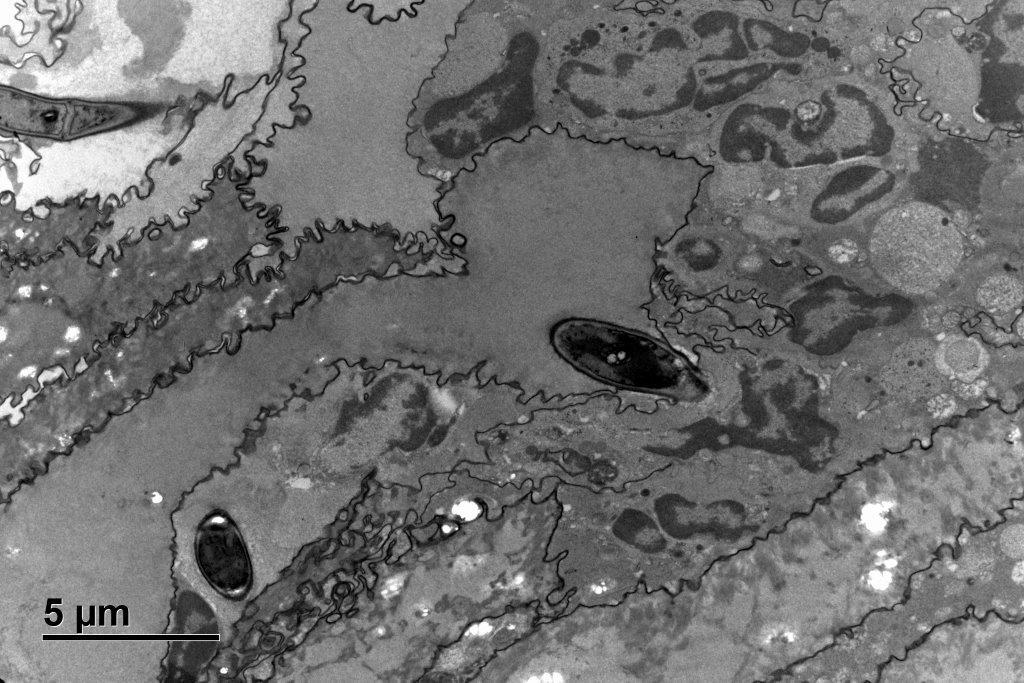

We meet the 42-year-old hunched over a microscope. She shows us cultured skin cells, which come up as polygonal structures attached to a plastic dish. Her expertise is around fungal infections and the protective mechanisms we have against these diseases.

The SNSF earlier this year said it saw a “need for action”External link in promoting the careers of young scientists – the post-docs – who are key for the country’s academic excellence. One fifth of the 2017-2020 budget of CHF4.5 billion ($4.7 billion) will go into career support measures. LeibundGut-Landmann tells swissinfo.ch why such support is crucial.

swissinfo.ch: Did you always want to go into research?

Salomé LeibundGut-Landmann: Yes, but I maybe wouldn’t have said that explicitly when I was 20 or so. I always wanted to understand the basis of life: how human and animal life functions and how that life is protected from all the many potentially dangerous microbes that surround us. Understanding these miracles better always made me, and still makes me, marvel about how perfect nature is and that’s a driver to do research.

swissinfo.ch: You followed a fairly classic academic career path, with a PhD and post-doc abroad. How did the SNSF professorship help?

S.L-L.: I was awarded this six-year fellowship when I completed my post-doc in the UK, the stage when I was curious to go on one step and become more independent. I was able to develop my own research programme during the last five and a half years, and I established myself as an independent scientist. I was involved in teaching and I trained students. This all is really critical in preparation for my next career step.

swissinfo.ch: The SNSF says there is a ‘strong need’ to support academic careers. Is it difficult for young researchers to get a foothold?

S.L-L.: I see the changes of career funding that are now going to be implemented by the SNSF with the new phase as a follow up of what has already been going on with other SNSF programmes like Marie Heim-VögtlinExternal link (for women with families), Ambizione External link(grants to lead independent research projects) and the SNSF professorships.

The new and adapted instruments of the SNSF support young researchers at the transition from postdoc to group leader. This is a critical phase and it’s exactly when many young scientists quit academia.

Salomé LeibundGut-Landmann

The researcher studied at the federal technology institute ETH Zurich before taking a PhD at the University of Geneva in 2003. She then did a post-doc from 2004-2008 at the London Research Institute of Cancer Research UK. This work inspired her interest in fungal pathogens and in interleukin-17-dependent immune mechanisms – which have emerged as a crucial host defence mechanism against fungal infections. “With our research we hope to gain a better understanding of the immune response, and the host protective mechanisms against fungal diseases, which is critical for future development of novel diagnostics and novel therapeutic strategies,” she says.

In 2008 she moved to the Institute of Microbiology at the ETHZ and in 2009 was awarded the SNSF professorship, with the funding period starting in 2010. In January 2015 she joined the University of Zurich to establish the section of immunology at the Vetsuisse faculty.

swissinfo.ch: Why is that?

S.L-L.: There are different arguments. The general fear is that jobs in academia are insecure, that job perspectives are not so clear. Although there are clearly opportunities in academia, careers are not always outlined. There is a need for mobility which people are not always prepared for. Also, jobs in academia are generally paid less well than in industry and that is an argument for some. Following a career in academia takes a lot of investment. There is competition and it’s not sure whether you will succeed. This makes people afraid.

swissinfo.ch: Women in particular are a target of the SNSF careers funding.

S.L-L.: The proportion of women dropping out of academia is still more significant than that of men. While the number of female students is high in many disciplines (e.g. > 50% in natural sciences and medicine, > 85% in veterinary medicine), women are not represented to the same degree at the level of professorships. Although the situation is improving – alongside a change in the general awareness, better childcare opportunities and fathers who are more open to helping at home than 20 years ago – women more often than men decide against an academic career. This is also because the time of starting an independent research group often coincides with the time of starting a family. In that sense it is a good investment by the SNSF to have a little extra support for women, as is foreseen with the new PRIMA programme.

swissinfo.ch: You have managed to combine research with having a family. How?

S.L-L.: For me it was never really a question of deciding either, or. May be I was influenced a little by the example of my mother who had four girls and always worked in science, also having her own research group.

To successfully combine a career with a family, it is important to agree with your partner how to share the tasks, so that not everything falls to the mother. The other essential thing is to delegate as much as possible (e.g. cleaning) and to use the time to either be at work or have quality time with the family. To me, playing with my children is relaxing and also provides me with new energy for work.

swissinfo.ch: What qualities do you need to make a success of being a researcher? Speaking to you, I would say passion is a main driver.

S.L-L.: Yes, passion and curiosity are the drivers for me as a scientist. Doing research is a self-driven thing that asks for perseverance and endurance. In return, academic research comes with the intellectual freedom. It’s my choice on which research topics I focus my interests. This is great. But being an independent scientist is not easy. Being a group leader means to taking on responsibility. And it requires confidence. There is not much room for being afraid of tackling next steps.

It also helps to care about people. As a scientist I do not work on my own: I have my research team and that is like my second family. My lab members are very different from my kids as they are a bit more grown up [laughs] but they are very important to me. I need to provide them a working environment that allows them to successfully develop their own research projects within the framework of the bigger project of the lab so that we are creative together. This team spirit is very important for all of us and supports us in finding the way through the jungle of sometimes difficult research questions.

Tenure track issue

The SNSF career support measures envisioned for 2017-2020 include: a new PRIMA (Promote Women in Academia) scheme, a boost for the SNSF Professorships to make them more flexible and upgrading funding schemes that promote scientific independence.

There will also be grants for assistant professorships with tenure track to support the planned establishment of such positions with clear-cut career prospects at higher education institutions. “There is really not a career path for academic careers in continental Europe, with a few exceptions. This is unlike the United States,” Martin Vetterli, president of the SNSF national research council told swissinfo.ch.

In the US you can get an assistant professorship on the tenure track which is “the natural road towards a permanent professorship. This tenure track position is relatively rare in Switzerland.” Having a clearer cut career progression is key to attracting young researchers, Vetterli says.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.