Facing your fears: neurons rewrite traumatic memories

Using mouse models, Swiss neuroscientists have identified the cells that help reprogramme memories of trauma towards those of safety – a discovery that has potential therapeutic applications for humans.

Memories of traumatic experiences can lead to conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It is estimated that almost a third of all people will suffer from fear or stress-related disorders at some point in their lives.

A study by scientists at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL) has shown, at the cellular level, how therapy can treat even long-term trauma memories. The results have been published in the latest edition of the renowned ScienceExternal link journal.

“When you want to overcome a traumatic memory, then it’s better to face it than to suppress it. While, this has been known in psychotherapy, at the level of the brain cells, we simply don’t know what is happening,” said EPFL professor Johannes Gräff, of the School of Life Sciences, whose labExternal link carried out the study.

“What we could show for the very first time is that the key to a successful treatment of a trauma lies in the very same cells that used to store this trauma. In the long run we hope this has positive implications for the treatment of PTSD,” he commented in an EPFL videoExternal link that accompanied a statementExternal link on the research.

The researchers conducted a fear-training exercise in which they placed mouse models inside a box and administered a series of mild foot shocks. This produced long-lasting traumatic memories; when the mice were traumatised, they stopped moving out of fear.

But after treatment for the trauma similar to exposure-based therapy in humans – in which the mice were again placed in the same box but without shocks – the animals went back to their normal movements. The researchers note in their paper that all animal experimentation for the study was approved by cantonal veterinary authorities.

‘Overwriting’ memories of fear

“Now what we can show is that the treatment of a traumatic memory is not mediated by two distinct memory traces, but it is rather an overwriting of the original memory trace of fear towards safety, which is happening,” Gräff explained.

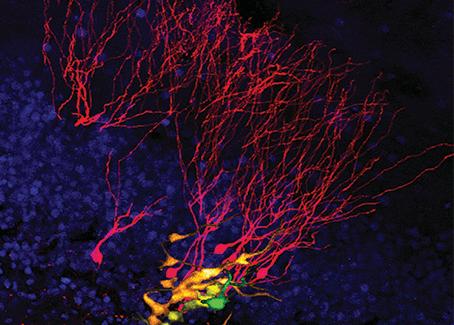

As shown in the main picture above, marked in green is a brain cell that was active when the mouse was still scared. After trauma treatment, the lab also tagged the cells that were active when the mouse was no longer scared, in red.

“What is clearly visible from this image is that there is an overlap, which stipulates that the same cells that were active when recalling a traumatic memory are also active when the mouse was no longer scared,” Gräff said.

“Now we know what happens at the level of the brain cells. In the future we want to look inside those cells, at the genes and at the DNA, to see how a trauma – and more importantly how a treatment of a trauma – affects those genes,” the professor concluded.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.