Science solves the mystery of the red lake

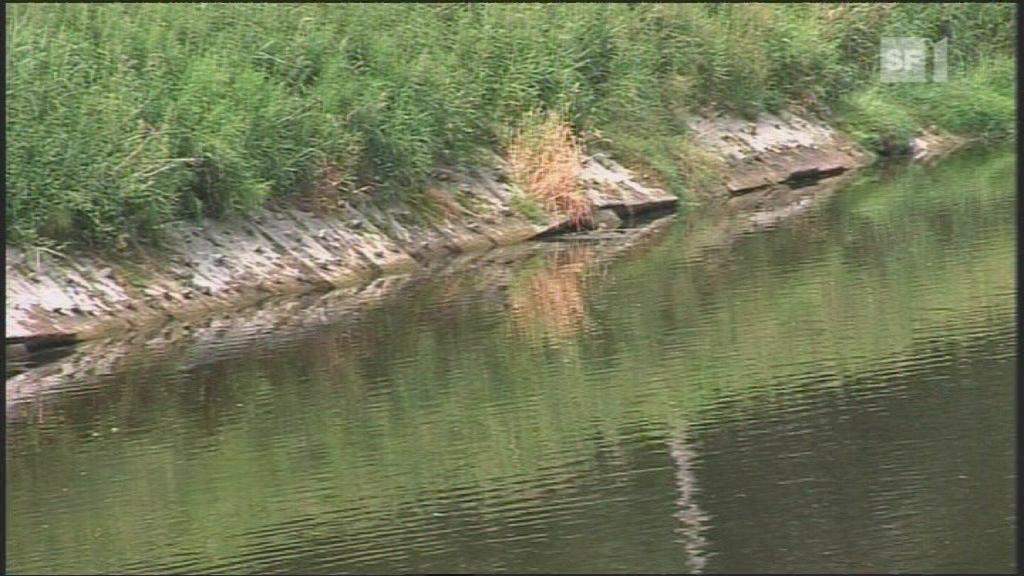

When the Seealpsee alpine lake suddenly turned blood red this summer, people were left scratching their heads as to what could have been the cause.

A Zurich-led team of researchers have now pinpointed the reason – a rare algal bloom Tovellia sanguinea, in what is only the second case of its kind in Europe and the first in Switzerland.

The 1,140-metre high lake, near the Säntis mountain in Appenzell Inner Rhodes in eastern Switzerland, suddenly turned red at the end of July. The head of the canton’s environmental protection department, Fredy Mark, was first alerted to the change by local farmers.

“At first I thought it was a case of damage, pollution from some sort of third party influence,” Mark told swissinfo.ch.

“We had the whole thing under observation and then we tried to do some analysis in the affected places to see what was going on up there.”

As word spread, the site became a tourist attraction with people from neighbouring Germany and Austria also coming to view the lake. Mark was inundated with messages and media enquiries.

Officials were perplexed. As they were not sure whether the red lake was harmful, they stopped taking drinking water from it.

Science CSI

A team of scientists from the Institute of Systematic Botany at Zurich University, the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich (ETH) department of earth sciences and Copenhagen University in Denmark decided to do some detective work.

After taking samples, they concluded that the colour had come from Tovellia sanguinea, a single cell organism of the dinoflagellante group of marine and fresh water plankton. The results were announced in August.

“This is rather an exciting discovery because nobody has found these type of organisms as a bloom in an alpine lake since 1964,” said Kurt Hanselmann, a microbiologist at the ETH.

This was in the Tovel Lake in the Northern Italian Alps, but there has not been a Tovellia sanguinea bloom there since. In fact, red algal blooms, similar to the one observed in Seealpsee, mostly occur in the sea.

Mark says the Seealpsee algal blooms occurred because the nutrient balance, temperature and light provided ideal conditions.

Nutrient question

For Hanselmann, the nutrient question is key. “Every time you have a mass development of an organism, you need the necessary nutrients that allows these organisms to build so many cells. You also need to find out where these nutrients come from,” he told swissinfo.ch.

“At the Seealpsee it’s clearly, in my opinion, an input from an intensive agricultural use of the land within the catchment.”

He added that the agricultural pattern was changed around the Italian lake, which could explain why there has been no bloom there for 45 years.

Blooms fading

The Seealpsee lake has now been officially declared safe, which Mark said was a relief. The bloom is now reducing in size and can only be seen in a few patches from above.

“With the same environmental conditions it is absolutely possible that it comes again next year,” said Mark.

Hanselmann says, although the phenomenon would be interesting to see again from a scientific point of view, it was “a bad sign for the health of the lake”.

He also warned that it was not known for sure whether Tovellia sanguinea could be harmful under certain conditions.

It has been shown that some dinoflagellates – around 70 of the 2,000 species – produce toxins. These are often behind the so-called “red tides”, such in the sea around Florida in the United States and along the Atlantic coast of France. These toxins, if they get into the food chain via seafood, could kill people.

Under observation

However, certain conditions are needed for toxins to occur, the scientist pointed out, and these are not found when an alga blooms. Toxins are normally released when the organism comes under stress, such as when it is depleted of nutrients.

For now both the researchers and the cantonal authorities are keeping the phenomenon under observation.

“If it blooms again we’ll try through further and extra tests to find out what climatic conditions are needed for this algal bloom,” Mark explained.

“This is very interesting for science and we are getting a lot of enquiries from central Europe about how the situation is developing and what we are doing now.”

Isobel Leybold-Johnson, swissinfo.ch

Kurt Hanselmann is part of a team which goes to investigate interesting phenomena in high mountain lakes. One of his cases was at Lake Totensee on the Grimsel Pass in the central Swiss alps, where there had been a mass fish kill a few years ago. There had been accusations that poison was the cause.

The team however found that a recent cold spell had plunged cold water into the stagnant lake, mixing up the water. The stagnant lake had stratified with the oxygen rising to the top layer of water. When it was mixed, the oxygen was depleted and the fish could not breathe.

At Lake Tambo in canton Graubünden in eastern Switzerland there had been unexplained cow deaths over a period of 25 years. Cyanobacteria reacting to certain conditions was found to be the cause. These became active after 4-5 sunny days and released themselves from their nutrient source at the bottom of the lake. Under stress, they produced toxins. If cows came into contact with the cyanobacteria mass they died within 20 minutes.

The solution was to pipe water (safe because the toxins were so diluted) to a fountain a couple of hundred metres from the lake. “A beautiful case in which science can solve real problems,” Hanselmann said.

“Red Tide” is a phenomenon caused by algal blooms that accumulate rapidly and discolour coastal waters.

The algal bloom can deplete oxygen and/or release toxins. Microscopic marine algae Karenia brevis, a dinoflagellate, released toxins which killed thousands of fish and marine organisms. These are known as harmful algal blooms.

The causes are thought to be, among others, warm ocean temperatures, low salinity, high nutrient content, and calm seas.

The phenomenon is found all over the world and has been increasing, reports say, since the 1980s. Large international research efforts are being made to better understand the causes of toxic blooms and their prevention (see GEOHAB link).

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.