Space junk: a Swiss warning to the world

Space debris is a real risk for orbital navigation, but there are ways to reduce it, says a Swiss report addressed to the relevant players. Will this be enough to dissuade militaries around the world from making space their playground?

On November 15 last year, some 480 kilometres above the vast Russian steppes, the satellite Kosmos-1408 exploded in silence, disintegrating into a cloud of debris of various sizes. Retired from service 40 years ago, the spacecraft had just been hit by an A-235 antiballistic missile, fired from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome.

Four hundred and eighty kilometres – that’s dangerously close to the orbit of the International Space Station (ISS). The seven crew members were immediately told to put on their space suits and take shelter in the emergency capsules which would bring them back to Earth if there was a collision.

At the Pentagon, Russia’s action was denounced as “reckless” and “dangerous and irresponsible”. Moscow responded that everything had conformed with safety rules. After all, there are two Russian cosmonauts on the ISS, one of whom is the commanding officer.

Collisions in space

This space shoot’em up was not the first of its kind. China in 2007, the US in 2008 and India in 2019 had already put on such a show of force – always on one of their own satellites.

There have also been accidental collisions. On March 22, 2021, the Chinese weather satellite Yunhai 1-02 struck a piece of a Russian Zenit-2 rocket launched in the 1990s. That was the worst orbital collision documented since 2009, when the Russian military satellite Kosmos-2251 hit Iridium 33, an American communications satellite.

Each of these incidents, whether intended or not, added several hundred bits of debris to what is already present in the low Earth orbit range (up to 2,000km altitude). There are already 34,000 pieces of space junk, counting only those that ground radar systems can detect. There are also around 130 million small bits of debris orbiting at 20 times the speed of a rifle bullet which are also likely to cause considerable damage on impact.

Ideas for a solution

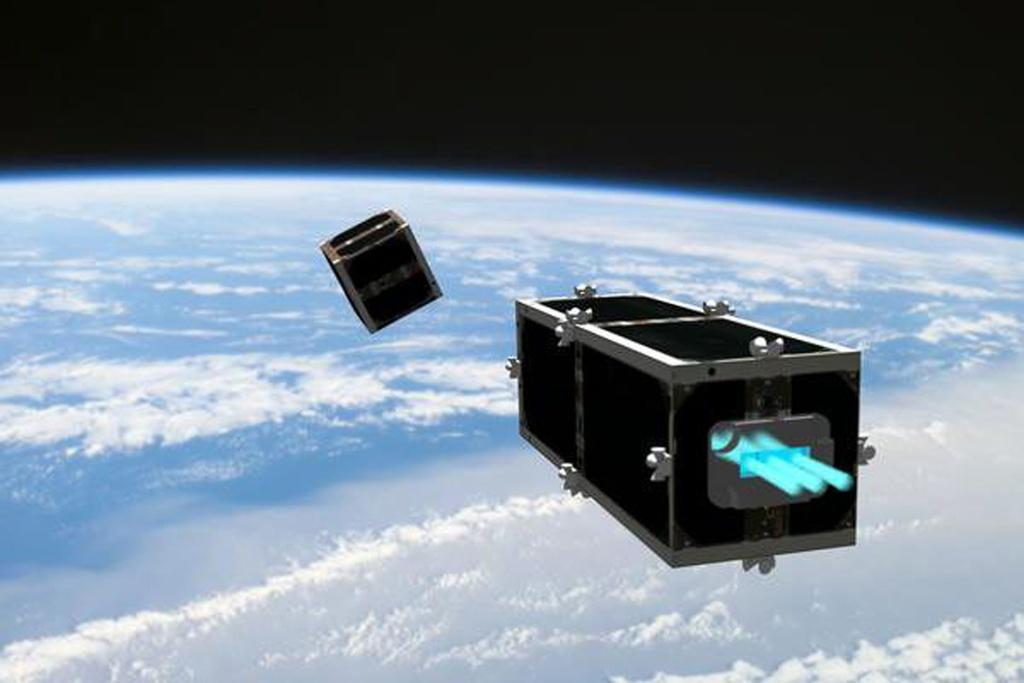

Today, space agencies and private-sector satellite launch companies as well as the research world are very much aware of the problem. Scientists at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL) have been working on it since at least 2012, when the ClearSpaceExternal link project was initiated. This is a project to develop the first satellite that can actually pick up space junk.

More

The world’s first space ‘garbage truck’ will be Swiss

However, decision-makers have not been convinced of the value of investing in such waste management solutions. Marie-Valentine Florin, director of EPFL’s International Risk Governance Centre, pointed out to Muriel Richard-Noca, co-founder of ClearSpace, that there was no comparative study of the various solutions and the costs involved.

This task went to Romain Buchs, a young physicist who had just completed a Masters thesis studying the issue of waste management in space. An initial reportExternal link came out in spring 2021, and at the end of November a set of options for political and industrial decision-makers was added.

“We targeted this paper at about 400 people in the space agencies and the private sector,” Buchs says, conceding that “it is difficult to reach the Chinese and the Russians” and that military leaders are not on the list.

“Normally these satellites are supposed to re-enter the atmosphere [and burn up] 25 years after their operating cycle is completed, at the latest. But the rule is not binding and it’s often ignored. About 60% of satellites follow the rule, though it should be at least 90%,” he says.

Small and large fry in orbit

Meanwhile, more and more satellites are out there. And for several years states have no longer had a monopoly on access to space. The trend has been for low-orbit satellite constellations. This began at the end of the 20th century with Iridium and Globalstar for satellite telephone communications. But there were barely 100 of these.

Following OneWeb, then Starlink (SpaceX) and Kuiper (Amazon), satellites were now in the thousands, supposed to bring fast internet access to the whole world. The operators promised to take all necessary precautions, keeping their spacecraft flying low enough for them to fall out of orbit automatically after a few years, or else fitting them with devices to facilitate their capture by future space pick-up craft.

For Buchs, these clouds of small satellites are not really the problem. “Basically, states have created the problem. The newer satellite constellations are most likely to get hit. Those are the little satellites, which weigh barely 150 kilos each. The real problems come from whole rocket stages – above all Russian ones – which may weigh up to nine tonnes each and which were jettisoned between 1980 and 2005,” he explains.

Getting a grip on the chaos

That said, Buchs doesn’t believe in apocalyptic scenarios such as the Kessler syndrome, which envisages near space becoming so crowded that further flights would become impossible.

“We’ll never be able to pick up all the small debris – we’ll have to concentrate on the big chunks, which may crash into one another and shatter into thousands more little bits. There are about 2,000 of them in low orbit. If we picked up just three or four of them a year, it would reduce the risk considerably,” he says.

This is the goal of the ClearSpace project, which started at EPFL and is now under the aegis of the European Space Agency (ESAExternal link). The Japanese now have a similar project (AstroscaleExternal link) and there will be others.

Meanwhile, if anyone thinks it would be enough to declare a moratorium on all new launches into orbit, they forget how much our world depends on satellites.

“Just to take one example, 26 of the 55 parameters used for measuring climate change can be calculated only from space,” Buchs says.

(Translated from French by Terence MacNamee)

More

Swiss scientists are first to see space junk by day

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!