Sticky gecko toes inspire internal bandage

Researchers have developed a waterproof internal bandage inspired by the adhesive principles of gecko lizards' feet.

Geneva University scientist Andreas Zumbuehl, who helped invent the bio-rubber polymer used to make the “gecko tape”, said the bandage could have a wide range of uses in repairing surgical wounds and internal injuries.

Zumbuehl and the multidisciplinary team of researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the United States spent two years studying the gecko to come up with the revolutionary internal plaster. Their research has just been published in the American journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“We had these crazy ideas, one of which was to take the principle of the gecko paw that sticks to any surface and to put it into a medicinal environment to tape together organs,” the organic chemist told swissinfo.

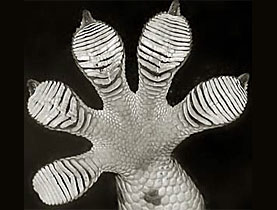

The gecko is able to defy gravity thanks to billions of tiny, specially shaped hairs on its toes. A combination of friction and adhesion forces allows it to securely cling to any surface and at the same time detach its foot easily when walking.

To create the bandage, the team invented a biodegradable, biocompatible elastic polymer, similar to a rubber band, which is very easy to produce.

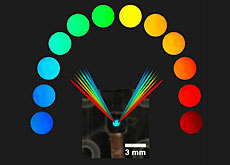

Then employing modern lithography techniques used to create computer chips, the polymer was poured into tiny silicon moulds with 200-500 nanometre-wide indentations to create the same hill and valley structures found on geckos’ feet.

After testing the samples on intestinal tissue taken from pigs, they selected the stickiest profile, one with pillars spaced just wide enough to grip and interlock with the underlying tissue. The nanopatterned adhesive bonds were found to be twice as strong as unpatterned adhesives.

The researchers then added a very thin layer of a glucose-based glue to create a strong bond and help the bandage stick in wet internal environments.

In tests of the new adhesive in living rats, the glue-coated nanopatterned adhesive showed a more than 100 per cent increase in adhesive strength, compared with the same material without the glue. And the new bandage provoked only a minor immune reaction that should not pose a significant problem in a clinical setting.

Patching up holes

Gecko-like dry adhesives have been around since about 2001 but there have been major challenges to adapt this technology for medical applications given the strict design criteria required: biocompatible, biodegradable and sufficiently flexible.

“It’s the first time that such ‘gecko tape’ has been successfully tested on an animal,” said Zumbuehl. “Many people have talked about it in a medicinal sense, but no one has actually demonstrated it before.”

“Gecko-type adhesives produced by other scientists haven’t been able to stick to organs.”

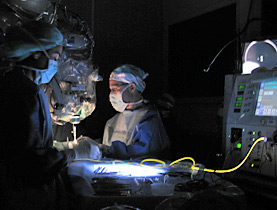

The researchers say the bandage has great potential for the operating theatre – and even the battlefield.

“It might not replace stitches and staples but it will be a big advance for surgeons, making a lot of things much easier,” said Zumbuehl.

The gecko tape is biodegradable and dissolves over time, so there is no need to remove it.

The adhesive could also be infused with drugs designed to release as the bio-rubber degrades. The elasticity, degradation rate of the bio-rubber and nanostructure can be fine tuned depending on the specific medical applications.

“This is an exciting example of how nanostructures can be controlled, and in so doing, used to create a new family of adhesives,” said team leader Professor Robert Langer.

According to the researchers, applications include patching a hole caused by an ulcer, and resealing the intestine after a diseased section has been removed.

Because it can be folded and unfolded, the bandage could also be used in minimally invasive procedures difficult to stitch because they are performed through a very small incision.

“It could repair arteries, tiny holes in the heart or other organs… just like a plumber uses duct tape to repair pipes,” said Zumbuehl.

swissinfo, Simon Bradley in Geneva

The mechanism by which the gecko is able to cling to a wall or ceiling is unique in nature.

The gecko foot is covered in hundreds of overlapping scales or plates. Each plate is made up of many millions of tiny hairs. There are about half a million of these hairs, called setae, on each of the gecko’s four feet. The tip of each seta has 100 to 1,000 tiny pads, called spatulae; and these are the key to the gecko’s strong adhesive force.

Scientists believe that as the billions of spatulae come into close contact with a surface, the weak interactions between molecules in the spatula and molecules in the surface create bonds that collectively are 1,000 times greater than the gecko actually needs to adhere to the surface.

These short-range forces that operate between atoms and molecules are known as van der Waals forces, after the Dutch scientist Johannes van der Waals (1837 – 1923).

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.