Study pinpoints “upheaval” in Jewish community

The most significant study of Judaism in Switzerland in 50 years has revealed a community in a state of major flux.

Many Jews no longer identify themselves with the rules of traditional orthodox communities and instead are joining more liberal groups, resulting in a pluralistic community.

The study, Swiss Judaism in Transition, was carried out as part of a Swiss National Research Programme review of the national religious landscape.

Researchers at Basel University’s institute for Jewish studies focused their work on the communities of Geneva, Basel and Zurich, which are home to around 70 per cent of the faithful.

They found a community in “complete upheaval”. Social change in recent decades has had a profound impact on the religious life of Jews.

While in the 1950s Switzerland only had orthodox communities, the “culture of openness” of the 1960s had resulted in a desire for more personal freedom and a tension between the demands of modern society and religious norms.

Now, of the estimated 18,000 Jews in Switzerland, 75 per cent belong to around 25 Jewish communities ranging from liberal to ultra-orthodox.

“It is an important study because it is the first scientific study of Jewish people in Switzerland since the Second World War,” Yves Kugelmann, editor-in-chief of the Jewish review, Tachles, told swissinfo.ch.

“What’s important to note is that the change in the Jewish community is a change happening in parallel with the whole of society. So the positive thing is Jewish people are very well integrated and emancipated. It is no longer like a ghetto in a society.”

Wedding bells

Mixed marriages between Jews and non-Jews are at the crux of the change, now accounting for over half of all marriages.

The study notes that “on the one hand this rapprochement towards non-Jewish society is a sign of complete integration”. But on the other it threatens Jewish traditions, since according to religious law, only children born from Jewish mothers are considered to be Jewish.

The study found that orthodox communities and their rabbis had reacted to mixed marriages by marginalising the non-Jewish members of these families. As a result those involved often decided to break away from a group.

From the 1970s new communities and groups sprung up that were more open to integrating non-Jewish members of mixed families.

Such communities were also boosted by changes such as the declining interest in making financial contributions or in spending time in community activities. Many believers also questioned the authority of rabbis, who were increasingly seen as outdated.

Reformist communities moved towards equality, doing away with the separation of men and women during religious services.

It is a trend that has been happening around the world. In the United States, the majority of communities are either reform or conservative, rarely orthodox.

“Pluralism and polarisation”

Consequently, orthodox communities see the openness in society as a danger and have been distancing themselves.

In recent years privately funded Jewish schools have been opening that put a greater emphasis on religious teaching. However this leaves some without enough skills to get a job, and ultra-orthodox families are commonly reliant on private or state funds, the study shows.

“There is a certain pluralisation and polarisation,” Daniel Gerson of the research team told swissinfo.ch.

“Our study went back about 50 years and there you can clearly see that some orthodox parts became very orthodox because they saw the changing world as more and more of a threat and began to build more invisible walls, especially by establishing Jewish schools for their kids.”

Gerson has followed up the study with an article on future scenarios for the Jewish community, published in last week’s Tachles.

He says ultra-orthodox believers will have “this ghetto-like existence which enables them to keep their folk together.

“In the not-so orthodox communities secularisation will probably continue and liberal communities will become bigger. And also there will be some very free kinds of communities without stable infrastructure [such as Jewish centres and cemeteries],” he said.

“An asset”

For Kugelmann, the study results are not surprising but are significant as they are based on empirical data.

“It is important now to have a point of view about which direction everything is going. It is important to have the results now in the National Research Programme. That means Jewish organisations and communities may have to change their policies.”

In Geneva, the head of the city’s Israelite community association, Roger Charteil, said it was too strong to say that the Jewish community was in the throes of a “complete upheaval” as the study states.

“There is pluralism. For me this is an asset. This diversity is very advantageous for Judaism.”

In the Middle Ages Swiss Jews were often persecuted, as they were elsewhere in western Europe. They were later subject to special taxes and laws which restricted their movements and activities.

In 1776 they were permitted to live in only two villages in canton Aargau: Lengnau and Endingen. At that time the Jewish population was about 550.

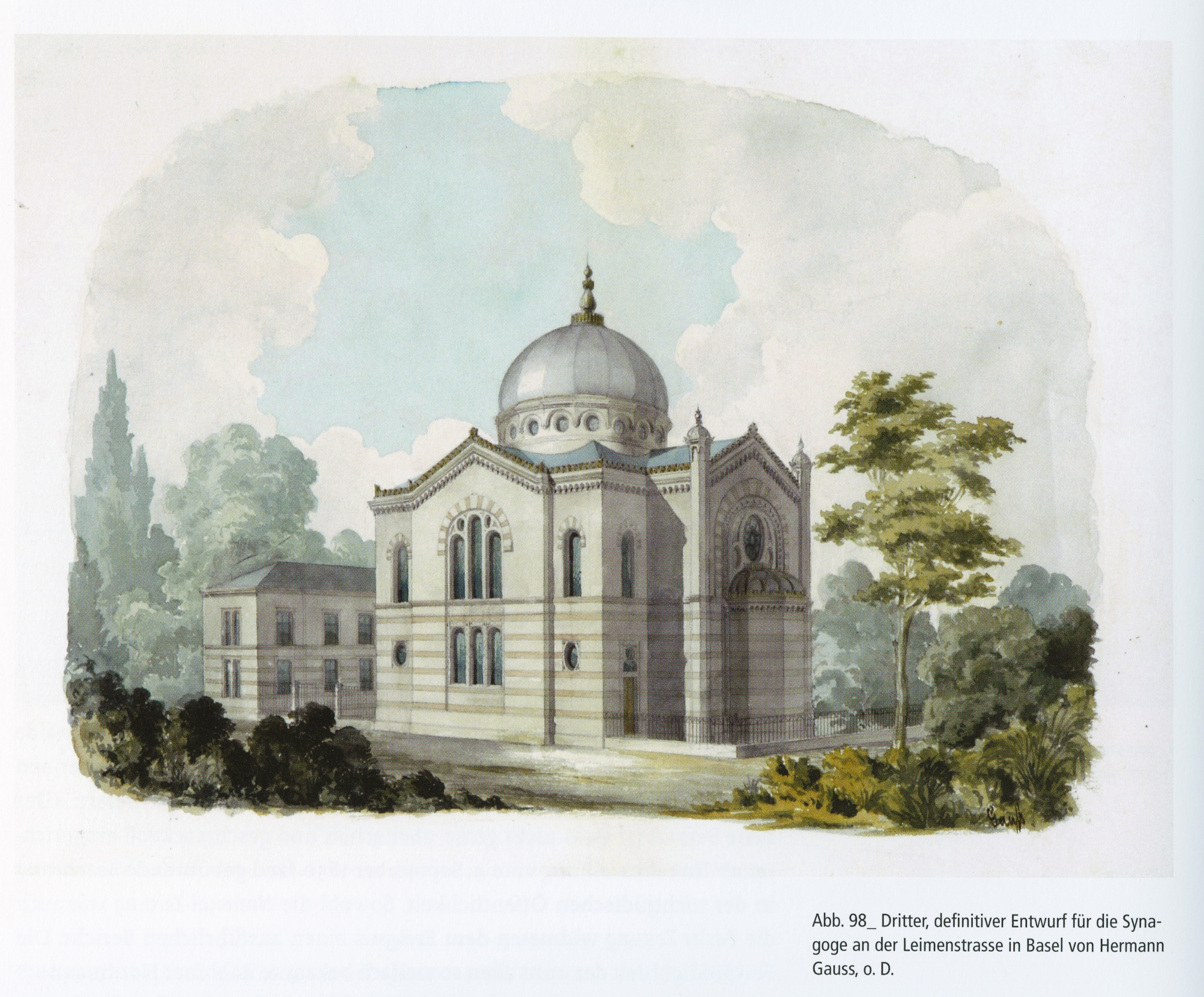

In the first half of the 1800s Jewish communities were founded in several Swiss towns, by Jews who had immigrated from neighbouring countries. They enjoyed greater rights that the Jews of Aargau.

Foreign governments whose Jewish nationals had settled in Switzerland, stepped up pressure for Jews to be treated equally.

Restrictions on Jews were gradually lifted; in 1879 the Jews of Aargau finally achieved total equality with all other Swiss citizens.

In 1880 there were 7,373 Jews in Switzerland, 0.3% of the population.

A wave of Jews fleeing pogroms in Eastern Europe started arriving in the early 20th century, changing the nature of Swiss Jewry.

During the Nazi period in Germany, Switzerland turned back many would-be refugees; however 23,000 Jews did find refuge in the country.

The 2000 census put the number of Jews in Switzerland at 17,900 (not counting those who may have described themselves as having no religious affiliation.) This is equivalent to 0.2% of the population.

A third of Swiss Jews live in Zurich. Around half of them are ultra-orthodox.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.