Meet the man who knows your family secrets

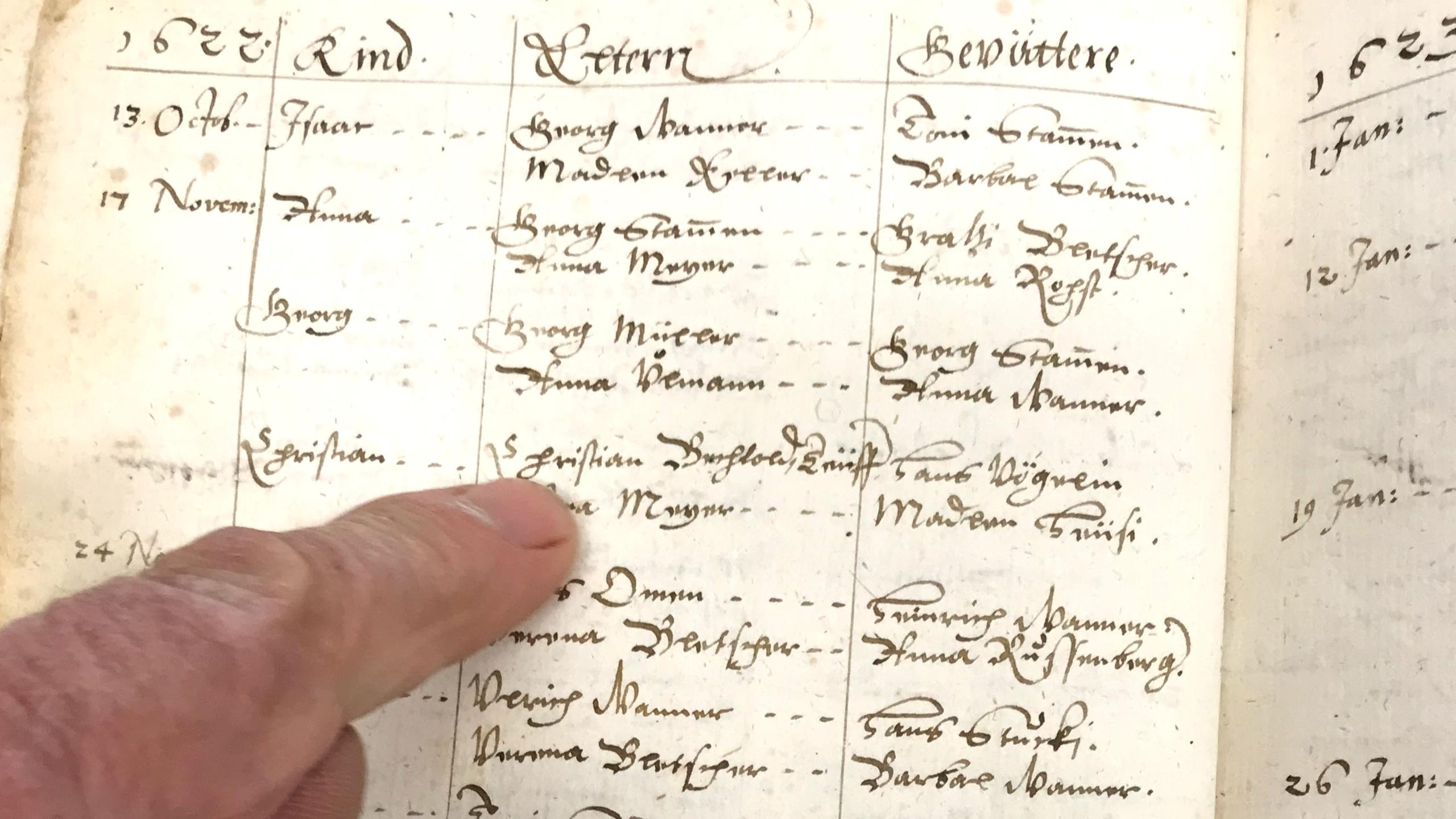

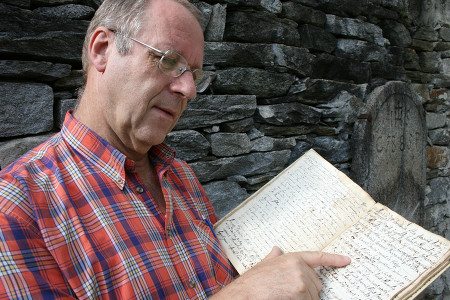

Willi Bächtold runs his finger along the brittle page and reads out the name of my earliest known ancestor, in an entry made in Old German script nearly 400 years ago.

Willi knows how much land Christian Bächtold held, how much tax he paid on it, how he was imprisoned for his religious beliefs, the details of his eventual breakout and recapture, and finally, how the family was expelled from Switzerland.

In fact, on request Willi can reassemble the histories of several old families that originated in his village of Schleitheim, whether Bächtold, Wanner, Stamm or Pletscher. Many of the queries come from abroad since the village – one of Switzerland’s northernmost communities – saw waves of inhabitants pack up and leave for Germany and eventually America due to religious persecution (they were Anabaptists – known as Mennonites and Amish today) or for Brazil due to economic hardship after failed harvests.

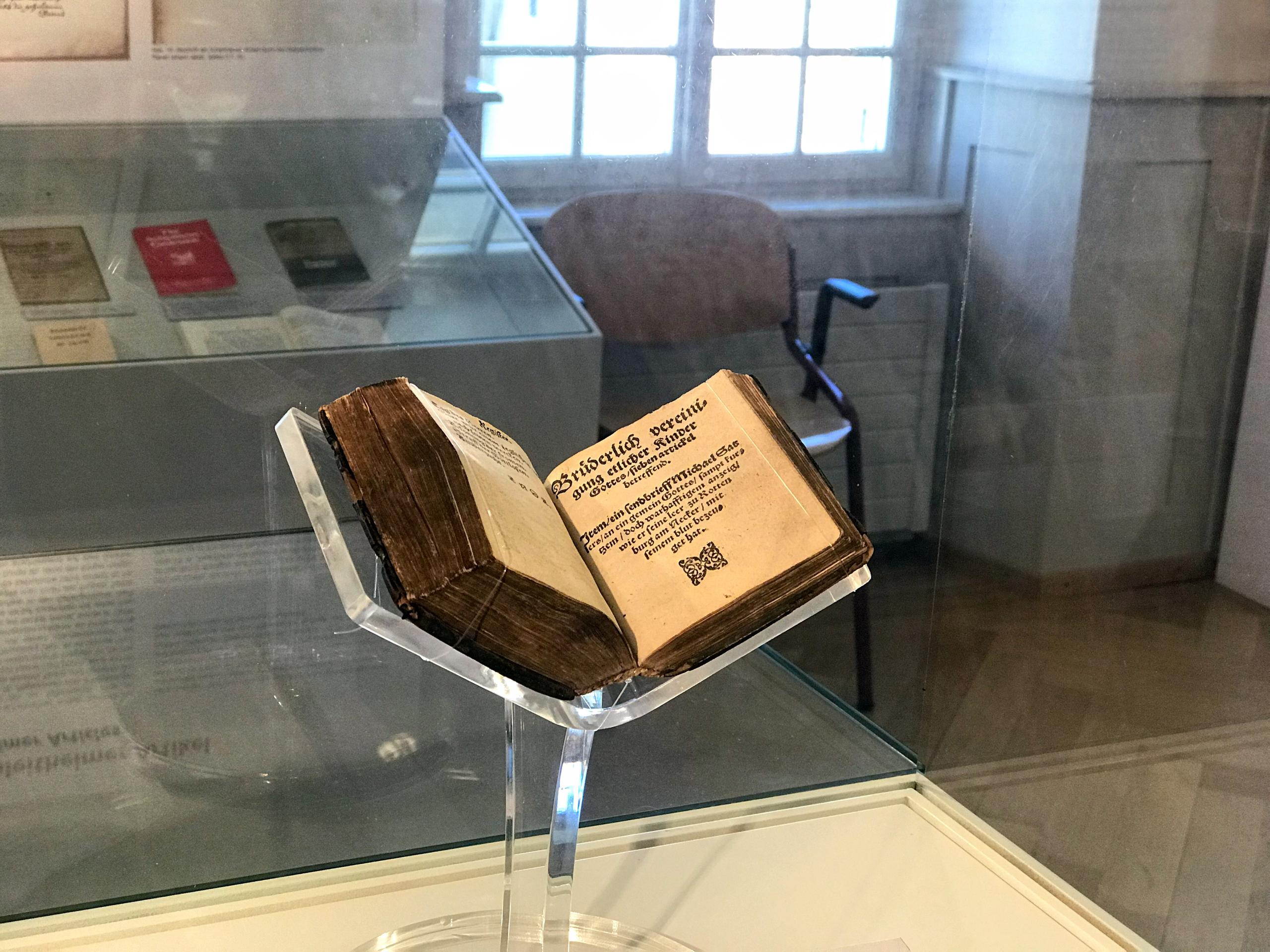

The demand for Willi’s services leapt after 2001, the year he secured through auction one of four original prints of the Schleitheim ConfessionExternal link that are known to be still in existence. The 16th century book of principles agreed by early Anabaptists helped define the movement.

The surprisingly small leather-bound edition, which fits snugly in the palm of one hand when open, is the centrepiece of a room in the modest village museumExternal link devoted to the history of the Anabaptists. It draws individuals and the occasional busload of visitors from far and wide who come to see the Confession in the very place the controversial religious text was agreed.

The fact that a rare surviving copy found its way back to Schleitheim is a testament to unselfish volunteers like Willi as well as a good portion of passion and village pride.

Bächtold co-runs the museum as president of the local historical society. The village, numbering just 1,700 inhabitants, is lucky to have him, as communities across the country are fortunate to have people just as dedicated to keep alive their own histories.

One in five Swiss communes boasts its own museum, a remarkable feat considering most of these places are villages or small townsExternal link, counting only a few hundred, or a few thousand residents at most.

“Many local and regional museums can only survive thanks to volunteers,” says Catherine Schott, head of the Association of Swiss MuseumsExternal link.

A survey by the association found that of the approximately 20,000 people who work in museums, nearly 40% do so without recompense. Yet, Schott says, many not only invest time but have to cover various costs too.

In return, volunteers are offered training courses organized by the Swiss branch of the International Council of Museums (ICOM), ranging from sessions providing practical tips on how to assemble an exhibition, to making a budget and fundraising.

“Willi is self-taught, but can hold his own with any academic,” Alex Stamm tells me. The retired architect is the secretary of Schleitheim’s historical society. “Willi is the clear leader and knows everything (about the region).”

Bächtold discovered his interest in history as a teenager. When workers were installing new water mains the curious boy went to see if their digging had surfaced any treasures. He was in luck, and gathered up several Roman pottery shards including a beautifully inscribed amphora handle.

Yet despite his inquisitiveness about the past, the village chronicler chose to study agriculture and then forestry, eventually becoming responsible for the management of the dense woods of the farming community.

That didn’t stop him from sating his appetite for more knowledge about his hometown, its people, and its quite remarkable place in history, both in Roman times and during the Reformation.

Bächtold eventually joined the historical society and in the mid 1980s, was asked by the village council to take over the local archives. And for nearly two decades, he was also empowered to perform civil marriages.

“I’ve always been interested in how people are related to one another, and the more you look into the connections, the more fascinating it becomes,” Willi says, as he pulls box after box of birth registries and records of landholdings off the shelves. The earliest documents in the climate-controlled room date back to the 16th century. They’re written in Old German the archivist has taught himself to read.

It’s this talent that enables him to dust off an ancient registry, flip the pages and find my ancestor’s four-century-old entry almost as fast as I can say ‘Google’.

Willi’s encyclopedic knowledge of the region’s history means he can also link the name and the period to the same person who was recorded in the cantonal records for being imprisoned for refusing to renounce his faith.

Have you checked the museums.chExternal link website to see if your ancestral village has a history museum? Finding out details about your ancestors may be a long shot, but at least you can learn about the place they once lived and what it was like before they emigrated.

Spending a few hours in Schleitheim, I’d like to think I’m admiring the same village landscape my forefathers would still recognize – broad half-timbered houses, a gentle stream running through the centre, fertile fields sloping up gently on both sides.

But the archives – and archivist – tell a different story.

A fire destroyed most of the buildings in the centre a century after my ancestors left. And about a 100 years after that, a devastating flood convinced the locals to build stone walls on the sides of the stream to prevent it from spilling its banks again. Around the same time, poor harvests across Europe forced families to seek their fortune elsewhere. Many inhabitants of Schleitheim emigrated to Joinville, Brazil, a town founded by Norwegians, Germans and Swiss.

Willi also shows me curious documents detailing rationing entitlements during the world wars, the correspondence kept from the local men’s choir, and the regulations of the society that oversaw Schleitheim’s 30 public fountains and adjacent washhouses, where families were given slots when they could do their laundry.

Most of the fountains still exist, but only five of the washhouses, Willi explains as we tour the village, pointing out one that has been converted into a storage shed.

The list of changes is long: Up until the year 1900, every family had its own vineyards, which stretched along the northwest slopes. Today there are only a few vintners left, cultivating a total of just three hectares.

Before the failed harvests of the 19th century, Schleitheim was at its peak, with a population of around 2,600, and 40 local pubs and restaurants to serve them.

Over a beer in the one of the four remaining establishments, Willi tells me about his current project. He’s putting local history into a firm geographical context by taking inventory of the largely forgotten border markers that circle the community.

The volunteer leaves no stone unturned.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.