Direct democracy expands in Germany

While the Swiss are voting on more issues than ever before, votes initiated by citizens in Germany’s 16 states are still rare. But calls for reform are growing, inspired by Switzerland.

Direct democracy is not a Swiss invention, but this system has been widely used and developed in the alpine republic since the 19th century.

So much so that Switzerland is seen as one of the most advanced democracies and held up as an example in many places.

A quick opinion poll by swissinfo.ch among passersby in Berlin’s busy Friedrichstrasse revealed a broad awareness of the Swiss votes in neighbouring Germany.

“I find people’s votes good because the citizens have a direct influence on decisions,” said Sybille Heine.

Another shopper, Irene Bamberger commented: “When the citizens participate, they accept the political decisions and don’t always complain about the powers-that-be.”

No nationwide votes

According to a survey by the research institute Emnid in November 2013, 84% of German citizens were in favour of citizen-initiated votes at a nationwide level.

Germany is one of the few Western democracies, where voters do not have a final say on nationwide issues, but only at a regional level.

Voters are not consulted on changes to the constitution and international agreements, and even major issues such as reunification or the Treaty of Nice, reforming the structure of the European Union, passed untested at the ballot box.

Some constitutional lawyers as well as citizens see an urgent need for action.

“With EU agreements and new countries joining [the EU], people should be able to vote. Then we wouldn’t have some of today’s problems,” said citizen Jürgen Fock on the streets of Berlin.

The law limits people power to the absolute minimum, calling them to vote only for parliamentary elections – every four years as a rule.

This distrust of the electorate is the result of the bitter experience of the Weimar Republic, when the Nazis came to power in democratic elections, as another passerby on the streets of the German capital comments.

“That bad experience has made me sceptical. And even now the population would not be immune to rabble-rousers,“ said Martin Meier.

Only at state level

What is not possible at a national level is at least possible on the state level. All 16 German states allow citizens to bring popular initiatives to the vote.

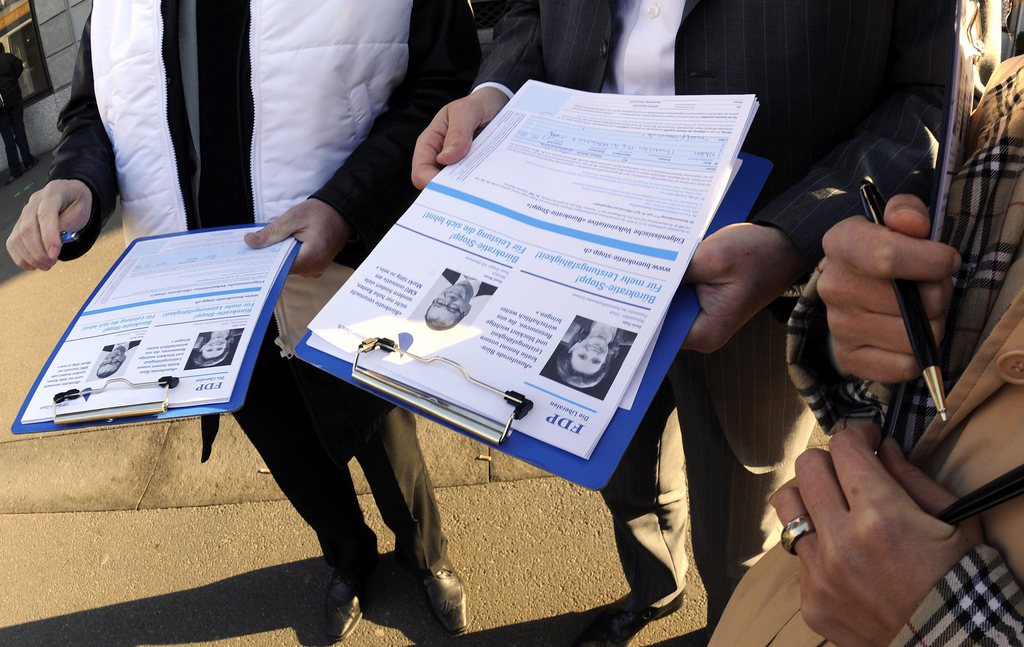

Similar to Swiss people’s initiatives, signatures have to be collected within a certain timeframe. If this is achieved, the state parliament must consider the proposal.

Even if rejected by parliament, the proposal is submitted to a popular vote, comparable with the Swiss system.

Only issues that lie within the remit of the 16 states can be addressed. Most votes are about school policy, transport projects or energy or water provision.

Despite these restrictions the direct democracy process is enjoying growing popularity, and there has been a significant increase in the number of such votes come to fruition in recent years.

According to the non-governmental think tank Mehr DemokratieExternal link (More Democracy) there have been 84 such demands from the public since 1966, 53 since the turn of the century.

In 22 cases these initiatives have resulted in popular votes between 1968 and 2014, most of them since 2000.

“Votes at a regional level are a good thing. I always participate in such ballots,“ said Sybille Heine from Berlin.

Obstacles

But that figure is low in comparison with Switzerland. Last year alone five people’s initiatives and six laws were voted on by the Swiss electorate in four separate nationwide votes, in addition to a host of proposals in the 26 individual cantons.

The reason so few votes make it through in Germany is the considerable legal obstacles that have to be overcome.

There are two aspects to this, according to Gebhard Kirchgässner, professor of economics at St Gallen University: the number of signatures necessary but also the time allowed for the campaign.

Whether an initiative comes to a vote essentially depends on the number of signatures required and the amount of time available to collect them.

While in Switzerland at least 100,000 signatures are required, equivalent to about 2% of the 5.2 million people entitled to vote, with 18 months to complete the task, the requirements in the German states are much more demanding.

The lowest level of participation for initiatives is in Brandenburg where campaigners have four months to collect 80,000 signatures – that’s 4% of the electorate. Hessen is at the other end of the scale, requiring the collection of signatures from 20% of the electorate in two months.

Different strokes

The reality of direct democracy varies significantly from state to state. Initiatives don’t feature in Baden-Württemberg and Saarland, while they lead to many public ballots in other states.

Of the 22 votes since 1968, seven took place in Hamburg, six in Bavaria and five in Berlin. The city states have comparably lower hurdles and an active civil society, and Bavaria is a special case with a long tradition of direct democracy. In all there have only been votes in six of the 16 states.

But it’s not only what happens ahead of a vote that is much more difficult than Switzerland.

The bar is raised very high for a majority vote to qualify. Voting quotas exist in almost all German states. It’s not just a question of getting a majority to vote yes but the yes voters also have to make up a minimum proportion of the electorate, usually 25%, a condition that requires a good turnout.

Call for reform

The high quotas in initiatives and votes have been criticised because they inhibit the active participation of the population, according to the Mehr Demokratie think tank. Some states have therefore started to ease the conditions, most recently Saarland in 2013.

At a nationwide level too, the call for more direct democracy is growing.

In the coalition negotiations last year, the Social Democratic Party and Christian Social Union supported popular, national ballot box decisions. However Angela Merkel’s party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), weighed in to exclude the proposals from the final coalition agreement.

Because reform requires a two-thirds majority in the German parliament, the CDU has been able to block other parties’ proposals until now.

Bavaria’s long tradition of direct democracy has a Swiss connection. Bavaria’s first prime minister after the Second World War, Wilhelm Hoegner, added people’s initiatives to the state constitution.

He was familiar with such direct democratic tools from the 11 years he spent in exile in Switzerland. Perhaps Angela Merkel will spend more time in Switzerland in the future?

In May of this year, the vast majority of voters in Berlin opted to keep the former Tempelhof air field as a park. The local government wanted to use part of the land for the construction of apartments and industry. The vote was held on the same day as the European elections and the quorum of 25% was reached.

In 2013 the initiative “New energy for Berlin” failed by a small margin. It demanded the return of the Berlin power network into public ownership and the founding of a public utility company. Although 83% voted yes, the initiative failed, falling just below the quorum at 24.1%.

A similar initiative in Hamburg was passed in the same year. 50.9% of voters accepted the initiative to transfer the Hamburg energy network back into public ownership. The vote coincided with local elections, achieving a turnout of 68%.

In 2011 a draft bill requiring the disclosure of the contracts for the partial privatisation of the Berlin water provider BWB was accepted by a majority of 98% and a quorum of 27%.

In 2010 the Hamburg initiative ‘We want to learn!’ was successful. It called for a partial roll back of parliament-backed school reforms. The vote was passed with a 58% yes vote, which represented just 22% of the electorate. But contrary to all other German states, Hamburg does not impose a quorum.

(Adapted from German by Clare O‘Dea)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.