Swiss look back on a tarnished wartime record

On the 60th anniversary of armistice day, swissinfo asks historian Jean-François Bergier if Switzerland has come to terms with its wartime past.

The surrender of Nazi Germany ended six years of horror for Europe, and was a huge relief for neutral Switzerland. The country had spent the war trying to avoid antagonising the Nazis, and had lived in constant fear of invasion.

As peace returned to Europe, the Swiss could feel good about neutrality, which had saved the country from destruction, and proud of their army, whose formidable defences had deterred the Nazis from invading.

But in the 1990s, uncomfortable revelations surfaced about Swiss banks handling assets looted by the Nazis and refusing to release details of dormant accounts held by Holocaust victims.

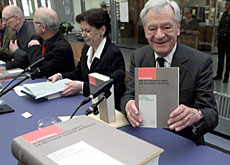

The scandals prompted the government to set up an independent commission of experts, led by Bergier, to investigate Switzerland’s wartime past.

The final report, published in 2002, shattered many myths about the country’s wartime history. Bergier’s commission found that government and industry had cooperated with the Nazis, and that Switzerland had turned away thousands of Jewish refugees at its borders.

The report also destroyed the idea that Switzerland’s defences had saved it from Nazi invasion, and highlighted the uneasy relationship the Swiss had had with Germany.

swissinfo: Where were you when the armistice was announced?

Jean-François Bergier: I remember that I had gone walking with a friend in the woods above Lausanne. Suddenly, we heard all the city’s bells ringing. We knew what it meant since we knew an armistice was about to be signed.

I ran as fast as I could to get home to say the war was over. I have a very strong memory of the happiness we felt that day. People were out on the streets waving Swiss and Allied flags. There was a sense of relief in the air.

swissinfo: Switzerland was neutral and not involved in the war. Can you compare its situation with that of neighbouring countries?

J-F. B.: No, it was not comparable since Switzerland was not occupied. The effects of the war were hardly felt except perhaps for the [accidental American] bombing of Schaffhausen. We were spared from death and grief, so you can’t compare our situation with that of our neighbours.

In Switzerland, we were afraid. We were outside the conflict, but at the same time we were surrounded by it. This was a fear that the end of the war helped to eliminate. The threat against our traditional values, democracy, was wiped out.

swissinfo: Many Swiss have said your commission’s report was too harsh on Switzerland. Some said they felt betrayed. Do you agree with this opinion?

J-F. B.: No, not at all. People are taking the wrong view. First of all it’s a report that only considers some critical points. It is not an all-encompassing review of Switzerland during the war. It wasn’t all negative either. We pointed out that neutrality helped safeguard Swiss institutions and protect our fundamental values against all odds.

To do this, compromise solutions had to be found and some mistakes were made, such as our refugee policy. We showed also that the Swiss economy sometimes went beyond what the Axis powers were demanding. But we have to admit that it was sometimes difficult for business leaders and the authorities to know where to draw the line.

swissinfo: For a long time, many Swiss thought military strategy was the reason the country kept its independence. How true is that?

J-F. B.: It’s very hard to say. A whole lot of reasons have been put forward as to why Switzerland was not invaded. Our defence was one of them. From 1940 onwards, the army made it credible that an invasion would be a costly and expensive exercise for the Germans.

But it is only one explanation among others. Until 1943, Germany also thought it could win the war, so Switzerland was relatively minor problem since it had no strategic value.

The Germans also benefited from an independent Switzerland with its own currency. Commercial exchanges allowed them to get their hands on Swiss francs, the only currency that could be traded around the world.

swissinfo: There were many Swiss who helped resistance movements from neighbouring countries or who worked towards ending the conflict despite the country’s neutral stance. Why has it taken so long to recognise their contribution?

J-F. B.: It wasn’t seen as the right thing to do. People who helped or collaborated with the Nazis were denounced. But those who worked with the Allies or who simply helped people in need were never recognised because it went against Swiss neutrality.

We know now that neutrality was never entirely respected by the warring parties or by the Swiss themselves. But all this was kept under wraps to ensure that neutrality was considered our supreme value, even though it is only a political instrument.

swissinfo: Israel Singer, chairman of the World Jewish Congress, recently called Swiss neutrality a crime. What is your reaction?

J-F. B.: It’s absurd. Neutrality is the opposite. Without it, Switzerland would have been drawn into the war and probably occupied by the Germans. That would have been the end of Switzerland’s Jewish population including refugees.

swissinfo: Has Switzerland made its peace with its wartime past?

J-F. B.: It’s probably too early to say so. Not entirely, that’s for sure. We have seen that a number of people will still not accept the revised vision of Swiss actions during the war based on archival sources.

The slightly tarnished image of Switzerland simply doesn’t go down well with some people, and not just the elderly.

swissinfo: Should the report’s findings be taught in schools?

J-F. B.: [Young people] should be made aware of the country’s troubled times. A nation’s history cannot be based on a mythology that was built up over 50 years. So our findings should be part of the school programme, but it’s up to other experts to decide how best this can be done.

swissinfo-interview: Scott Capper

Jean-François Bergier was born in 1931 and comes from Lausanne.

In 1969, he was appointed was professor of history at the Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich.

In 1999, he was chosen to become the president of the Independent Commission of Experts looking into Switzerland’s wartime past.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.