Swiss museum examines collection of Nazi-era art dealer

Bern’s museum of fine arts has organised an exhibition to untangle the thorny legacy of the Gurlitt estate. The controversial collection is at the heart of debates on how to deal with Nazi-looted art.

“Taking stock means being accountable” is written in large letters on the walls of Swiss capital’s museum of fine arts. The Kuntsmuseum BernExternal link is holding its third exhibition on the controversial Gurlitt art collection. This time the exhibit puts emphasis on provenance rather than the art works themselves. The museum has spent eight years unpacking the fraught history of this collection, confronting legal, political and moral predicaments at every turn.

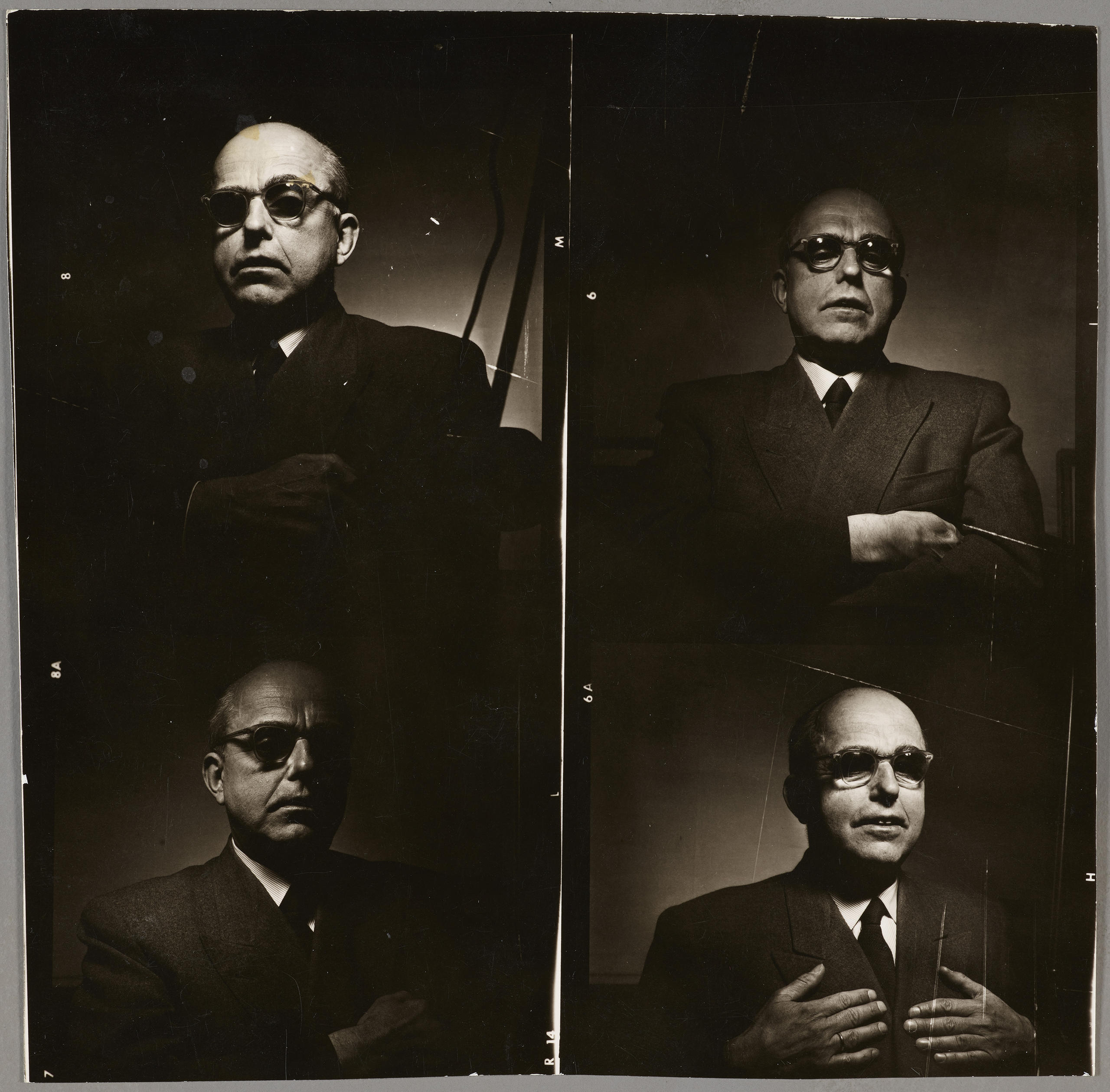

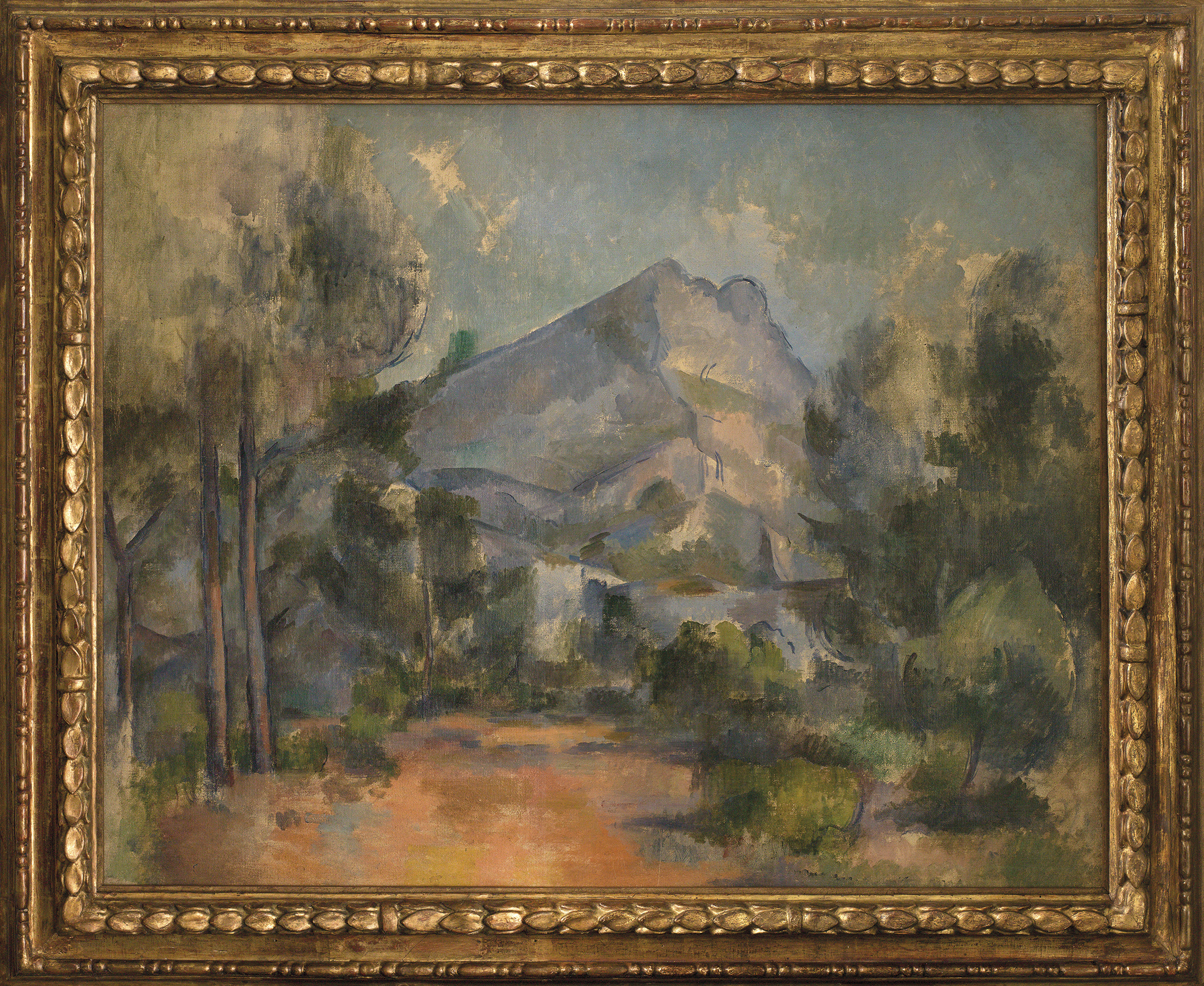

Art collector Cornelius Gurlitt bequeathed his inheritance to the Kunstmuseum Bern in 2014, two years after his vast collection – largely acquired by his father Hildebrand Gurlitt, a Nazi-era art dealer – was confiscated in Germany. The Gurlitt collection caused an uproar when German authorities stumbled upon it by chance in 2012; it triggered a public reckoning over how to deal with Nazi-looted art. German, Swiss and international media painted a picture of a collection of Nazi-looted property worth billions.

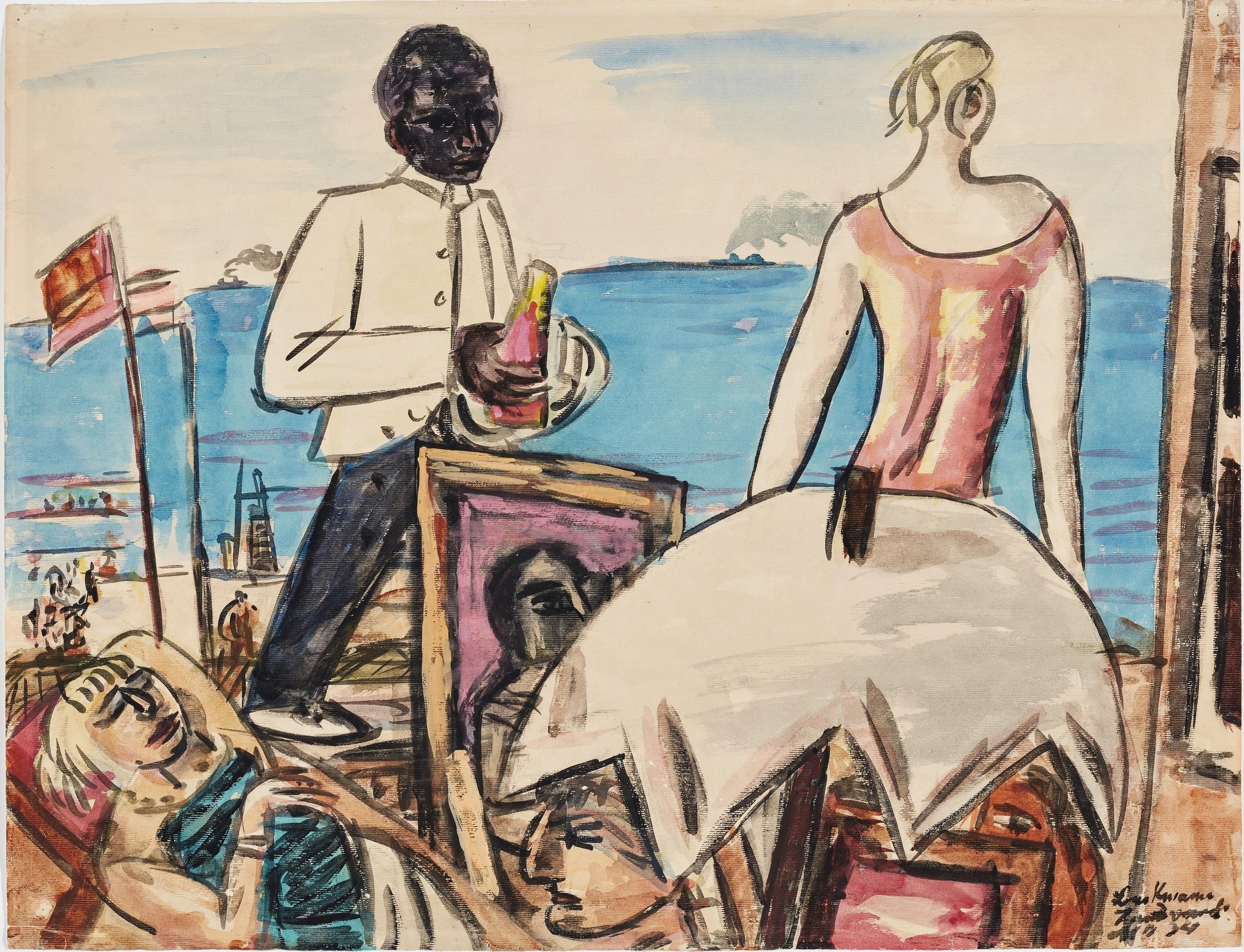

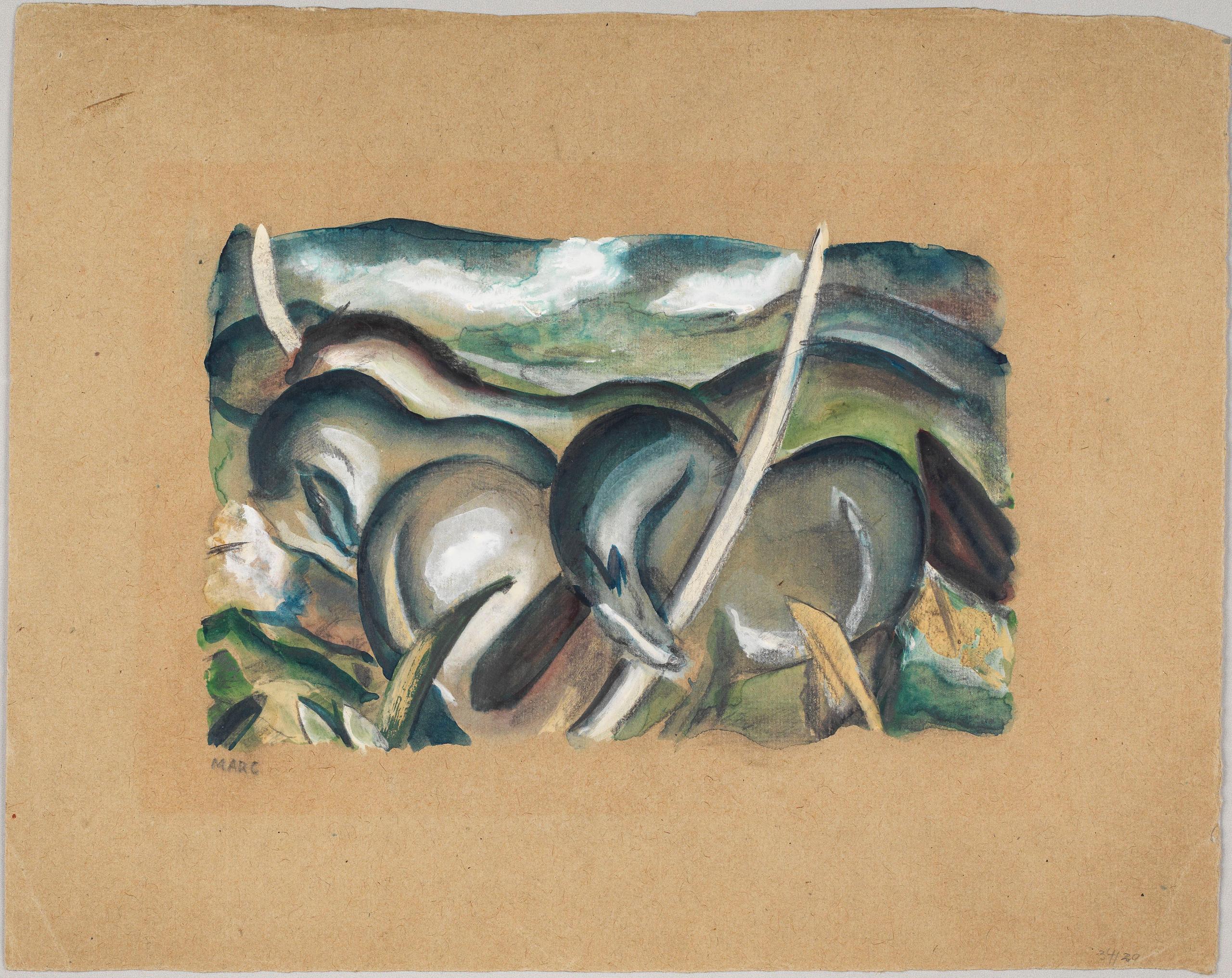

But that portrayal of the collection did not quite stand up to scrutiny. In December 2021, over 1,600 works came to Bern. In total, only a few dozen pieces were returned to rightful owners as looted art or to Germany to ascertain provenance. Questions remain – not only because Hildebrand Gurlitt manipulated works to conceal their origin, but also because much was irretrievably lost in the tumult of the Second World War, including documentation, knowledge and witnesses.

A German story with a Swiss twist

It caused some astonishment in the art world when the works were bequeathed to the Kunstmuseum Bern. This seemed a typically German story: how to deal with art stolen or traded by the Nazis, or works tainted by their influence. Even decades after the war, questions of moral responsibility and just restitution have by no means been answered satisfactorily. Dealing with legal and political legacies from the Nazi era was a matter for top-level cultural politicians in Germany.

The Swiss connection, however, was always there, even if many did not want to recognise it. Switzerland has always been a hub of the international art trade, and the Gurlitts often sold their works through Swiss middlemen. This was not morally questionable in all cases, but it was not always innocent either.

The Kunstmuseum Bern committed itself early on to a transparent approach to the Gurlitt legacy. In 2017 it founded the first department for provenance research in Switzerland. This approach set new standards with a traffic light system: works whose provenance was unobjectionable were ranked green. Works classified as red – meaning they were clearly Nazi-looted art – were rejected. The vast majority of the works fall in the amber-green category, meaning the provenance information is incomplete, or amber-red (a smaller portion). In the latter cases, there are hints the provenance is problematic and the case for restitution is being examined.

Open questions

The latest Gurlitt exhibition is the logical consequence of this commitment to transparency. It debates and showcases the museum’s approach to provenance research and the challenges confronted. What cannot (yet) be conclusively clarified is deliberately left open.

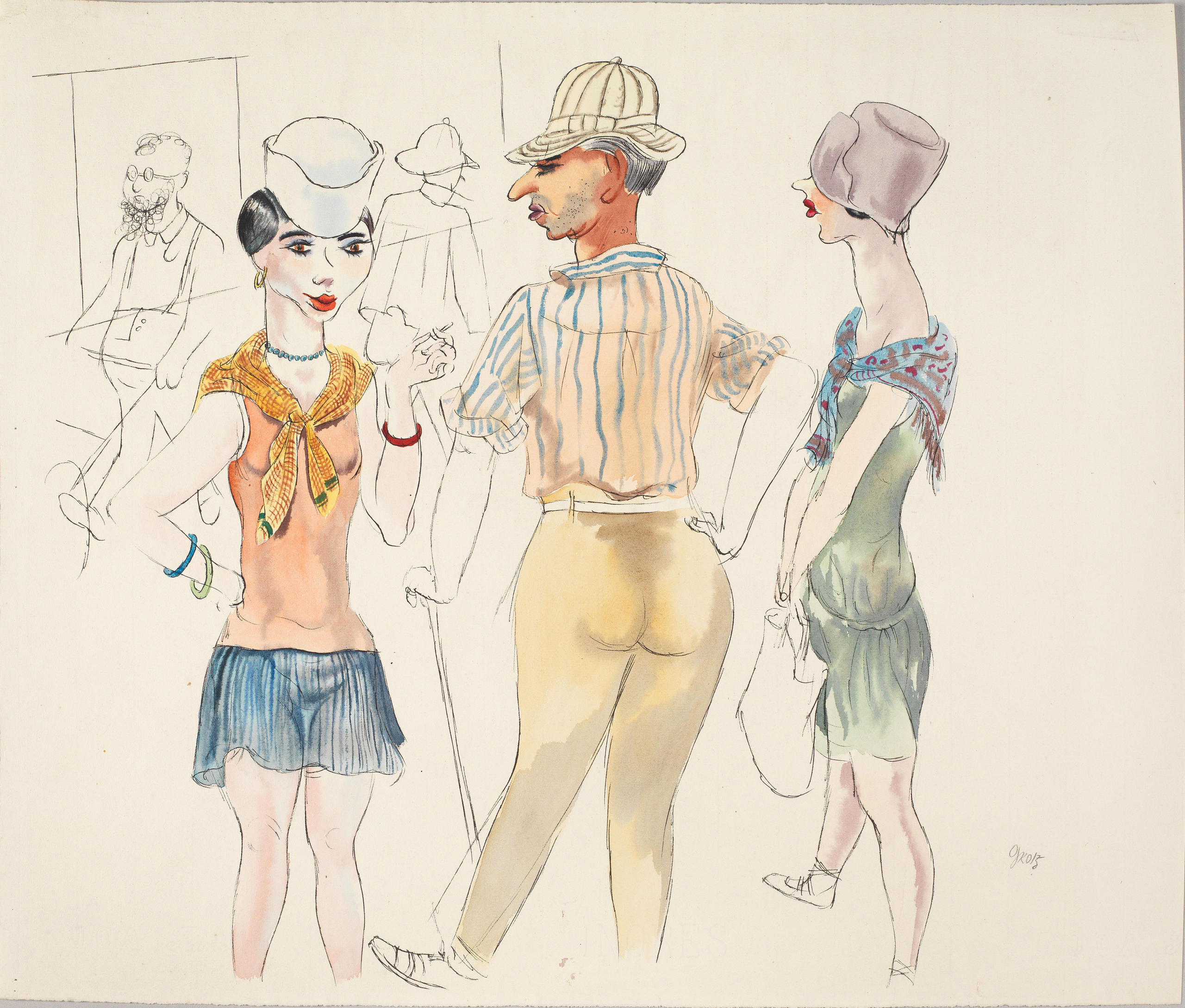

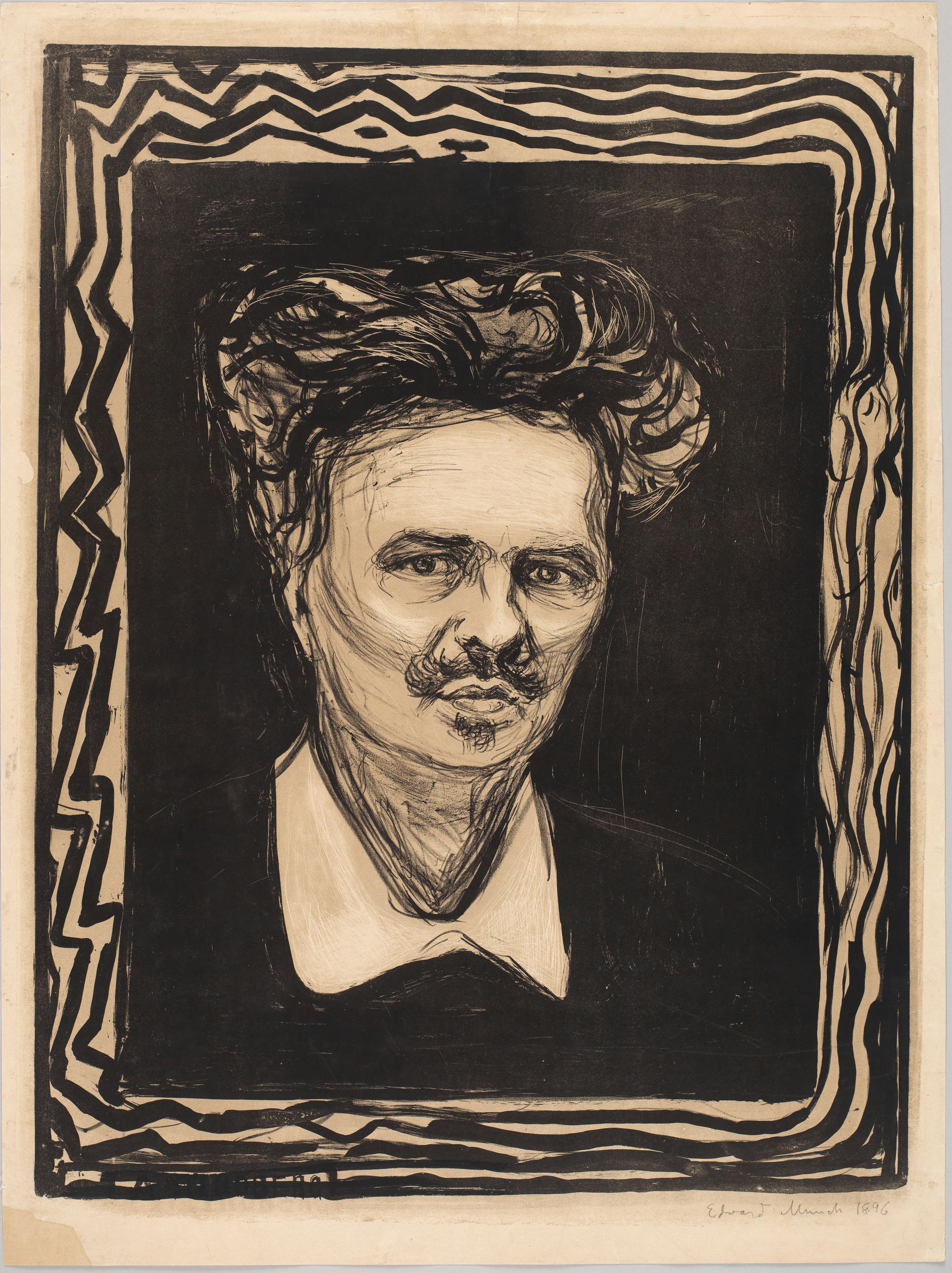

For example, the character of Hildebrand Gurlitt himself. The exhibit notes he had a Jewish grandmother and was therefore considered by Nazis to be a “Mischling” (a pejorative legal term used in Nazi Germany to designate persons of mixed Aryan and non-Aryan descent). That meant he suffered many social disadvantages, even if he was spared persecution. But he was also one of only four art dealers commissioned by the National Socialists to sell “degenerate art” abroad. He was able to save many works from destruction. Some ended up in his collection. Others he sold for profit.

At what point do you become a victim, and at what point do you become a perpetrator? And how can pure opportunism be combined with a rational survival instinct? Life in a dictatorship is always full of contradictions, as this exhibition powerfully demonstrates.

The “Taking stock. Gurlitt in review” exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Bern External linkruns from September 16, 2022 to January 15, 2023.

More

The new director of Zurich’s Fine Arts Museum is not afraid to fail

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.