Switzerland returns stolen artefacts to Italy

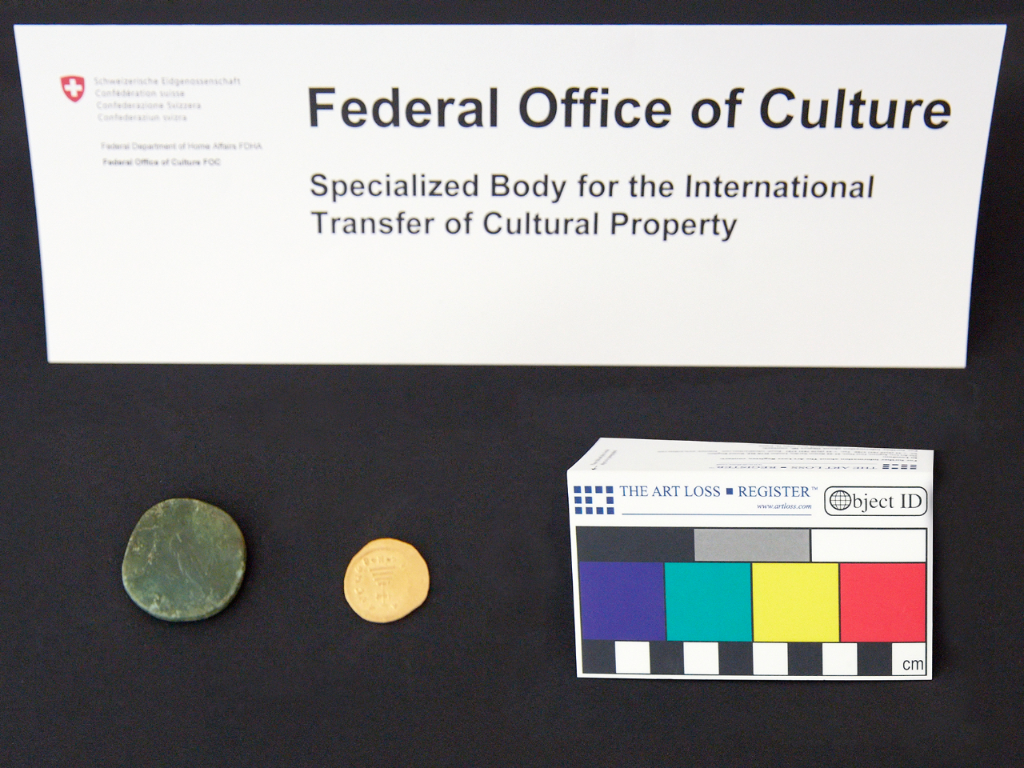

Switzerland, once a favoured destination for stolen cultural artefacts, is now working closely with the Italian authorities to secure the return of such treasures. The latest handover: 27 objects of inestimable historic and artistic value.

The return took place on October 13 at the Italian embassy in Bern. The Swiss authorities handed over 26 Etruscan artefacts from a private collection and a 2,000-year-old marble bust which was found at the Geneva free port.

The illicit trafficking of cultural artefacts is the world’s third-largest illegal market, after drugs and weapons. Countries such as Italy, which has a rich cultural heritage, have been striving for decades to stem this phenomenon.

The Swiss-held artefacts from the Etruscan period were collected in Tuscany by a Swiss citizen who has since passed away. “They were amassed between 1965 and 1968 in the Tuscan archipelago and were returned on a voluntary basis,” explains Carine Simoes, head of the Specialised Body for the International Transfer of Cultural Property within the Swiss Federal Office of Culture.

A marble bust, dating from between the first century BC and the first century AD, depicts a naked male figure partially covered by a chlamys (cloak).

After the discovery of the illicitly acquired marble bust at the free port, the Geneva judicial authorities ordered its seizure and return to Italy. No further details of the operation are available, as the investigation is still under way.

The deputy commander of the Carabinieri Department for the Protection of Cultural HeritageExternal link, Colonel Danilo Ottaviani, was present at the handover of the artefacts to the embassy. He expressed his satisfaction at the swiftness with which the process had been carried out.

“It is a clear sign that cooperation between the two countries is working better and better, and above all leading to concrete results,” he said.

The embassy handover was just the most recent Swiss return of cultural property to its rightful owner. As the Lugano lawyer and expert in art law Dario JuckerExternal link explains, stolen cultural property represents a vast illegal market.

“This problem was particularly acute in Switzerland for many years, because of a longstanding lack of appropriate legislation,” he said. So far in 2020, the Swiss body for the international transfer of cultural property has organised four returns, including two to Italy.

Italian-Swiss cooperation

This proactive response would not be possible if Swiss-Italian relations were not so close. It has not always been the case, however. The illegal trafficking of cultural property became an important subject of discussion in Switzerland at the end of the last century, when the problem of how to deal with assets confiscated from Jews during the Second World War was in the public eye.

The historically rather passive cooperation between Switzerland and Italy for the protection and recovery of cultural heritage reached a turning point in 1995.

It is one of the most protected and secret places in Europe. Over an area of 150,000 square metres, countless and multifarious objects worth an estimated $100 billion are stored: paintings by Picasso, Rembrandt and Leonardo da Vinci, but also precious stones, antiquities, finest wines (reportedly millions of bottles) and much more.

Originally intended as a facility for storing goods awaiting import or export, over time, some warehouses in the Geneva free portExternal link turned into giant safes, where speculators and swindlers from around the globe deposited their precious spoils, far from the prying eyes of tax and customs authorities. Today, however, things have changed somewhat. All goods entering and leaving the free port are now checked. Since 2007, customs officers have been able to search the premises. But the role of Switzerland’s free ports remains ambiguous.

In that year, the Geneva judiciary seized a large number of archaeological artefacts stored at the Geneva free port (around 4,000 objects, with an insurance value of over CHF20 million ($22.2 million).

The operation was triggered by an Italian request to Switzerland for assistance in the context of criminal proceedings against an Italian art dealer for the theft, handling and illicit appropriation of archaeological remains.

The investigation, which was the fruit of cooperation between the Carabinieri and the Geneva police, as well as judicial interaction between the Rome and Geneva law courts, brought to light the existence of a laundering ring for artefacts stolen from Italy.

As revealed during the investigation, objects stolen in Italy were illegally transported to Switzerland and sold through Sotheby’s, Christie’s and Bonhams (one of the world’s oldest and largest auctioneers of art and antiques), to then be bought back by the criminals themselves through Swiss shell companies, thereby creating a “legitimate” provenance for the objects. Once laundered, the artefacts were resold, either through auction houses or to private collectors and willing museums.

The objects seized in Geneva were returned to Italy only five years later, in 2000, by decision of the Federal Court, which rejected the final appeal by the Italian art dealer – who, in the meantime, was also sentenced to ten years in jail and fined €10 million (CHF10.7 million).

As part of the same investigation, an art gallery run by an Italian citizen in Basel and five of his storage depots at the Basel free port were searched in 2001. This led to the confiscation of around 6,000 archaeological finds originating from thefts, illegal excavations and the pillaging of sites, as well as files containing over 13,000 documents (invoices, letters to buyers, photographs of artefacts and more).

Fighting back with legislation

These two episodes prompted the Swiss government to ratify the 1970 Unesco ConventionExternal link in 2003. In June 2005, the Law on the International Transfer of Cultural Property, implementing the Convention, came into effect. It regulates the import of cultural artefacts into Switzerland, their transit through the country and their export. The Alpine nation finally sought to do its part to preserve the cultural heritage of humanity and to prevent, or at least limit, the theft, looting and illegal import and export of cultural property.

“The return of goods unlawfully removed from a country works better if there is a real will to collaborate between two nations,” explained Jucker. Italy and Switzerland have learned to work together and to trust each other.

In October 2006, a bilateral agreement was concluded between the two countries, which came into force in April 2008. This was the first such bilateral agreement signed by Switzerland. Others ensued, with Greece, Colombia and Egypt, and some years later also with China, Peru and Mexico.

Signing agreements and adopting new lawsExternal link are the tools used by Switzerland to try to ensure that the country is no longer singled out as a platform for the transit of stolen artworks.

Organised crime

Powerful criminal organisations are behind the illicit trafficking of cultural goods, according to Jucker. The black market is flourishing, with deals reportedly worth billions of dollars.

The extensive investigation by the Rome Public Prosecutor’s Office at the turn of the century, which led to the seizure of stolen artefacts in Geneva and Basel with the help of Swiss prosecutors, brought to light a violent criminal organisation dedicated, for over three decades, to the international trafficking of archaeological artefacts.

The objects mainly came from the illegal excavation of Italian sites (above all Selinunte in Sicily), which were exported illegally to Switzerland in order to be subsequently put on the international market. According to the investigating magistrates, the Italian art dealer, originally from Castelvetrano, which is a few kilometres from Selinunte, was linked to Cosa Nostra.

It is precisely to combat such cases of large-scale organised crime that Italian-Swiss collaboration is essential, according to Ottaviani.

Crossroads for illegal trafficking

From a legal perspective, the bulk of the work has now been done, although, as Jucker points out, there is still no agreement covering more recent works of art. So the question remains open whether Switzerland is still a crossroads for the illegal trafficking of cultural property.

Representing the official Swiss view, Carine Simoes says, “according to information from the federal police and UNESCO, Switzerland is no longer a favoured location for the illicit trafficking of cultural goods.”

But from Ottaviani’s perspective, Switzerland is still a transit State for licit and illicit artworks, like many other countries. The black market for art is global and no one is completely exempt.

The continued existence of seven free ports does not help Switzerland in its quest to shake off the uncomfortable label of crossroads for the illegal trafficking of cultural goods, which is something the country would like to do once and for all.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.