Switzerland’s wait-and-see approach to nuclear ban treaty is sensible

Switzerland helped negotiate an international treaty that seeks to eliminate all nuclear weapons, but it has not yet signed or ratified it. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and its global security implications could further complicate Swiss decision-making on the matter, says an expert on nuclear arms control.

From June 21-23, dozens of countries gathered in Vienna to discuss how to implement the new UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW)External link. They were joined by nuclear disarmament activists from around the world, including hibakusha – atomic bombing survivors from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Swiss diplomats were also present, but only to observe rather than directly participate. This may seem surprising, but it’s consistent with Switzerland’s pragmatism on questions of nuclear abolition.

At present, 66 countries have ratified the TPNWExternal link and become states parties. Switzerland, which helped negotiate the treaty in 2017, is not one of them. It might therefore seem like Switzerland isn’t committed to eliminating global nuclear weapons. But that interpretation would be a misreading. In fact, the cautious Swiss position may allow the country to build bridges between TPNW proponents and nuclear-armed states while sorting through its own concerns about the treaty.

Switzerland’s decision was based on careful study. Following a report by an interdepartmental working groupExternal link, the government opted not to become a TPNW member in 2018 and 2019. Instead, the country wants to work on nuclear disarmament with states inside and outside the treaty. Practically speaking, this means sending Swiss experts to observe TPNW proceedings. And that engagement is a good thing because the nuclear ban treaty is here to stay and cannot be ignored.

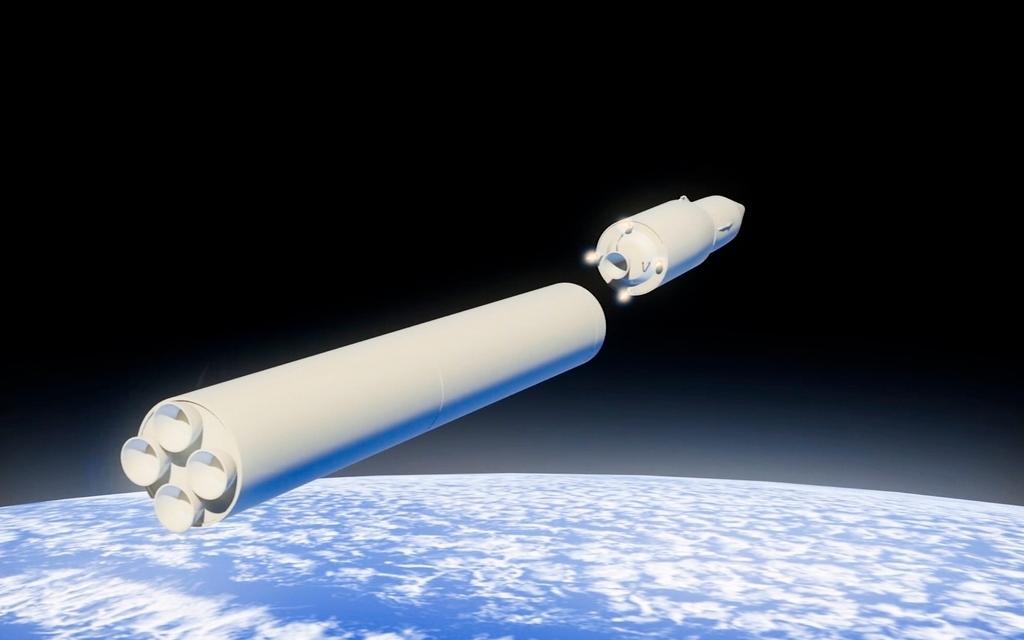

To understand the Swiss context, it’s important to take stock of this new treaty. The TPNW entered into force on January 22, 2021, when Honduras became the 50th state to ratify. It prohibits all states from engaging in nuclear weapon acquisition, production, testing, possession and threats. Its advocates hope to stigmatise nuclear arms as unacceptable instruments of statecraft with devastating humanitarian consequences. On paper, there appears to be little reason why Switzerland, which does not have nuclear weapons, wouldn’t join. The technology of nuclear weapons has, after all, created a dangerous world where certain leaders can destroy the urban population centres of their adversaries in a matter of minutes.

In practice, the TPNW’s ability to lead to disarmament is controversial. The nuclear-armed states – China, France, India, Israel, North Korea, Pakistan, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States – and the vast majority of their allied countries protected by “nuclear umbrella” pledges haven’t participated in any of the talks. Most of these countries claimed they would never join and that the treaty wouldn’t eliminate a single bomb or missile. Their scepticism is understandable, as the TPNW, like past treaties, says little specifically about how nuclear disarmament could be achieved or verified.

Still, this universal ban on nuclear weapons would mark a sea change from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) of 1968External link. That treaty, to which Switzerland is party, calls for disarmament but allows China, France, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States to maintain nuclear arsenals before the eventual realisation of a nuclear-free world. Many TPNW proponents justifiably critique the NPT for its lack of fairness in dividing the world into “nuclear haves” and “nuclear have-nots”.

More

Government’s stance on nuclear ban under scrutiny

The NPT doesn’t lay out a concrete disarmament plan either, and progress toward this goal has been slow. It does, however, empower the International Atomic Energy Agency to carry out inspections to detect violations and deter new states from building the bomb. And the United States and Russia have claimed that the tens of thousands of nuclear weapons they eliminated after the Cold War were dismantled in support of the NPT.

The Swiss position

The government’s working group was not solely negative when assessing the nuclear ban. It shares the TPNW’s view that nuclear weapons are fundamentally incompatible with international humanitarian law. This is hardly unexpected. Many of today’s nuclear weapons are orders of magnitude more powerful than the bombs that razed Hiroshima and Nagasaki; their use would be tantamount to mass murder of a speed and scale never seen in human history.

Switzerland has advanced civilian nuclear energy knowledge and technology, but the working group noted that the country wouldn’t be affected by TPNW provisions that prohibit supporting nuclear weapons programmes of other states. Switzerland already has oversight and export control mechanisms that regulate this sector.

These points align with the idea that eliminating nuclear weapons will remain a central foreign policy goal of Switzerland and all other countries seeking peace, justice and security. Unfortunately, there are around 13,000 nuclear weapons in today’s worldExternal link. This is far fewer than the 70,000 that existed at the Cold War’s peak, but nine countries still have nuclear arsenals while dozens more rely on assurances from nuclear-armed states.

So if there are moral and humanitarian reasons to ban nuclear weapons, and doing so would not hurt the Swiss economy, why would Switzerland remain on the sidelines? The answer comes down to two central security reasons.

The Swiss position is that Switzerland can support the TPNW once it becomes apparent that it will help, rather than hinder, worldwide nuclear abolition. The fear is that a treaty banning nuclear weapons without support from nuclear-armed states may conflict with existing – but greatly stalled – disarmament commitments under the NPT. It will take some time until the relationship between these two treaties is clear.

The second reason for Switzerland remaining outside the ban is geographic. The government’s working group expressed concern that TPNW attempts to stigmatise the bomb would only gather support in democracies with robust public debate. After all, France and Germany will obviously have more open discussions about nuclear policy than China or Russia. A world free of nuclear weapons is clearly in neutral Switzerland’s interests. A world where Swiss neighbours who help provide regional stability are weakened by nuclear disarmament, but their rivals are not, isn’t in Switzerland’s interests.

Impact of Russia’s war in Ukraine

The Swiss national statement in ViennaExternal link at the recent TPNW meeting recalled these past discussions, as well as how Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has changed international politics. It criticised Russia for nuclear threats and provocations. It also pointed out that Switzerland will need to evaluate the European and international security environments when making a new decision on the TPNW. Regardless of the outcome of the next assessment, which will begin later this year, Switzerland will continue to constructively engage with nuclear ban members and non-members.

There is little doubt that a world free from threats of nuclear war and annihilation is in the interests of Switzerland and its residents. A pivotal question is under review: Is the new nuclear ban approach going to make a strong contribution to eliminating nuclear weapons, or will it further polarise the “nuclear haves” and “nuclear have-nots”? Put more simply: Is it the right tool for the job? It may very well be. But before Switzerland can join, it must become clear precisely how the TPNW will improve Swiss security compared to other existing tools for nuclear disarmament.

Swiss diplomats have long leveraged their neutrality to build bridges between other countries that could not agree on divisive political topics. The Swiss wait-and-see position and observer status in the TPNW meetings could very well allow the country to do so again.

Edited by Sabrina Weiss

More

Can the city of peace stop the arms race?

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.