Gold market has dark corners

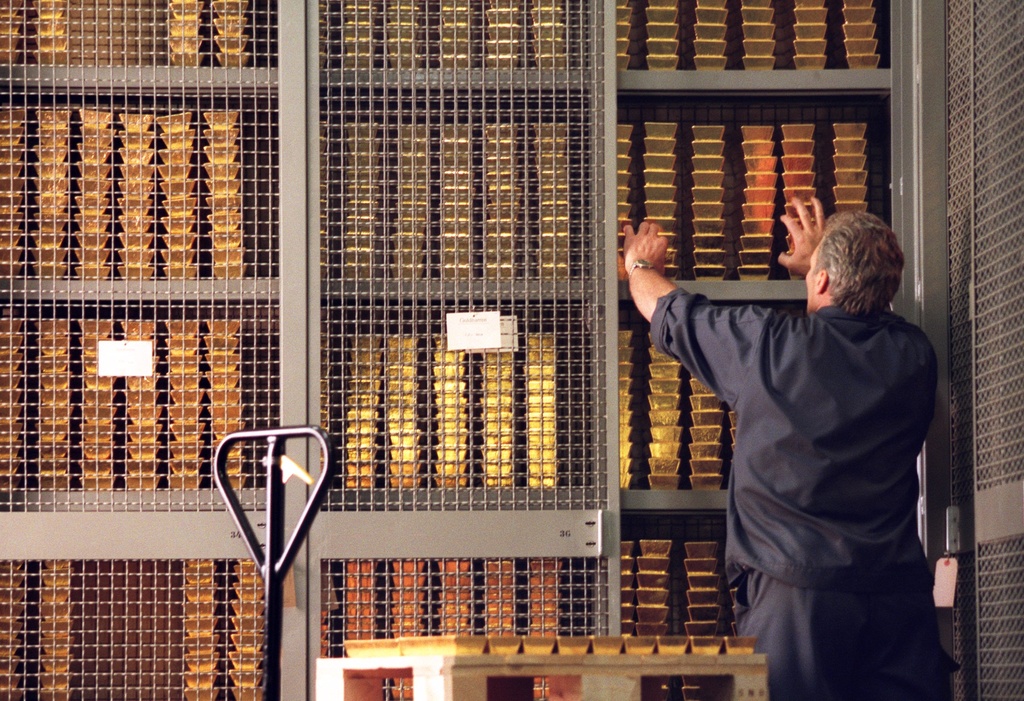

Switzerland has no gold mines, but it is the world centre for gold refining. There is little transparency in a sector in which human rights violations and pollution are a fact of life: some of the gold coming to Switzerland is none too clean.

The latest case came to light a few months ago. In Peru, about 30 individuals and four companies are under investigation for illegal mineral extraction and money laundering. In the space of a few years they are said to have sold about 25 metric tons of gold, worth $900 million (SFr846 million), obtained from illegal mines in the Amazon region of Madre de Dios, where 20 per cent of Peruvian gold is extracted.

Where did this gold end up? It is believed to have been sold to two Swiss companies, MKS (Switzerland) SA in Geneva, which owns the Pamp refinery in Ticino, and Metalor in Neuchâtel.

Through its spokesman Frédéric Panizzutti, MKS told swissinfo.ch that it has carried out investigations of its own in Switzerland and in Peru. The findings have not yet been made public, but Panizzutti said that “there is nothing there to cast suspicion on the legality of the supply in question,” and nothing has emerged which would require the company to notify Switzerland’s Money Laundering Reporting Office (MROS).

“The Peruvian gold refined by MKS is exported legally. It comes from small local mines registered with the Peruvian authorities that comply with government regulations regarding the traceability of gold.”

Of the 1,625 notifications received by MROS in 2011, only one concerned trading in precious metals. In view of the sums involved – over 2,600 metric tons of gold to a value of SFr 96 billion were imported into Switzerland in 2011 – can it be that there is really no problem?

“In the precious metals sector, the number of clients and transactions is considerably lower than in the banking sector. The refineries work mainly with institutional clients, not private ones like the banks. In 2003, the predecessor of the federal authority charged with regulating financial markets (Finma) reported the existence of 14.5 million private accounts in Swiss banks, as against probably less than a thousand in the precious metals sector,” said Panizzutti.

But Finma spokesman Tobias Lux pointed out that “the legislation on money laundering concerns financial intermediaries trading in gold. A foundry that buys raw gold and produces ingots is not subject to that legislation. You always have to make a distinction between production and trading.”

Traceability

Marc Guéniat, of the non-governmental organisation Berne Declaration, thinks that the gold industry and the raw material sector in general are particularly opaque: “From the initial intermediaries, transactions often come through a maze of offshore companies, located in jurisdictions where no-one can tell who the real beneficiary is.”

The Peruvian case is not the first in which Swiss companies have been involved. Recently, the Metalor refinery was named in the report of the group of experts of the UN charged with monitoring sanctions against Eritrea. Gilles Labarthe, a journalist who has authored several investigations on precious metals trading (including a book on African gold), says the group imported about ten metric tons of gold from Eritrea between February 2011 and July 2012.

Earlier, the Swiss refineries were associated with imports of gold originating from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, says Labarthe, who in 2010 was invited before the foreign affairs committee of the Swiss parliament as an expert on issues of money laundering and transparency in the sector.

Metalor rejected the accusations and said it carefully monitors its entire supply of gold, from the mine to retail sales, and takes serious steps to ensure the metal does not come from criminal activities, from a war zone, or places where human rights violations are common.

Clean gold?

In the past few years, players in the sector have taken numerous initiatives intended to guarantee a “clean” supply chain, such as Conflict Free Gold, the Responsible Jewellery Council or the LBMA Responsible Gold Guidance.

“Every year we are subjected to external audits to check if we are respecting all these rules,” explained Panizzutti, whose company took the initiative in introducing the regulations.

For Labarthe, the steps taken by the companies are going in the right direction, though he wonders if they will be enough to solve the problems, since these initiatives are voluntary and abuses are rarely punished.

Guéniat is even less impressed. “This kind of action is like letting a road racer decide what speed is legal and do the speed checks himself,” he said, adding that the list of members of the Responsible Jewellery Council includes companies known for their irresponsible behaviour.

The issue of ethics is not just confined to the regulatory framework, counters Panizzutti. “On a motorway you can travel at 120 km an hour. That doesn’t mean that you can’t decide to do it in an environmentally friendly car. The Swiss companies are already applying the strictest standards in the world as regards traceability of gold, and our company is committed to an equitable model of business.”

Gap in statistics

As regards the origin of the gold refined in Switzerland, surprisingly little is officially revealed. Since 1981, the countries of origin have not been named in the Swiss statistics.

“Throughout the 1970s and 1980s Switzerland was criticised for importing gold from South Africa, which was under an international embargo. Also, in the Cold War days there was a need to hush up imports of gold from the Soviet Union,” explained Labarthe.

Cédric Wermuth, a member of parliament for the centre-left Social Democratic party, recently took up this issue, requesting that the government to do something about changing the reporting practice. The government’s response was basically that technical considerations have not changed since the last time the matter was studied. Nevertheless, it added that “the political, economic and social context has evolved and the government intends to reexamine the issue of publishing details of exchanges of gold.”

In Labarthe’s view, these statistics would certainly be useful. The problem, he says, needs to be resolved at the level of the international institutions.

“Traceability should extend from the point of production to the point of arrival. In the case of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the gold, rather than arriving directly in Switzerland, was going through Dubai. These days Togo exports tons of gold. Officially, though, there are no mines in that country.”

China: 355 metric tons

Australia: 270

United States: 237

Russia: 200

South Africa: 190

Peru: 150

Canada: 110

Ghana: 100

Indonesia: 100

The sale of uncut diamonds has been used by various armed groups in Africa to fund conflicts.

The United Nations first took measures to end this trade in 1998, when it banned the trading of Angolan diamonds through unofficial channels, in order to prevent the Unita rebel group raising funds.

Similar measures were taken subsequently to try to end conflicts in Sierra Leone, Liberia, the Ivory Coast and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Diamond-exporting countries and representatives of the industry met in Kimberley, South Africa, in 2000 to work out a system to combat the illegal market and guarantee to buyers the legal origin of gems.

In 2001 the World Diamond Council was established, whose purpose is to certify the origin of raw diamonds.

In 2002, with the approval of the UN, the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme was set up, which brings together industry, states and NGOs in inspecting the origin of diamonds.

This tool is now considered insufficient by most NGOs, says Marc Guéniat, of the Berne Declaration, in particular “because abuses have not been punished”, notably in Zimbabwe, Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Could the Kimberley agreement at least serve as a model for better regulating the market for gold? Guéniat says the challenge here is much more difficult, because gold can easily be melted down: “Its real origin is hard to determine, compared to diamonds.”

(Translated from Italian by Terence MacNamee)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.