Techno in the village: the rise and fall of a rave mecca

In the 1990s thousands of ravers made the pilgrimage to the Swiss village of Roggwil, population 3,750, to party in abandoned warehouses. SWI swissinfo.ch talks to the locals about the time their village became a rave mecca.

It all came to an abrupt end on June 23, 2001. A fire broke out at the old Gugelmann spinning mill site at the northern end of the village. It took more than 300 firefighters two days to extinguish the blaze. Huge plumes of smoke billowed along the Jura Mountains towards Grenchen. The local population was told to keep their windows closed.

Several warehouses, a music club and event equipment worth hundreds of thousands of francs went up in flames. “Techno is over in Roggwil,” wrote the Berner Zeitung newspaper.

Just two months before, 12,000 people from all over Switzerland and abroad had danced the night away at one of the monster raves for which the village in canton Bern had been famous both at home and abroad for the best part of a decade.

The new electronic music genres of house and techno first emerged in the United States in the 1980s, and by the end of the decade had slowly taken over the dance floors of European clubs and discos, from the cities to the countryside.

Empty factories

Back then trainee electrician Mirosch Gerber, who had grown up in the village of Wynau next to Roggwil, developed a passion for electronic music. Shortly after starting his apprenticeship in the old Gugelmann textile factory in 1986, the now 51-year-old began collecting vinyl records and working as a DJ, first spinning disco before moving on to acid and techno.

The thrill of music took Gerber to England, where he not only bought records but also attended his first warehouse rave.

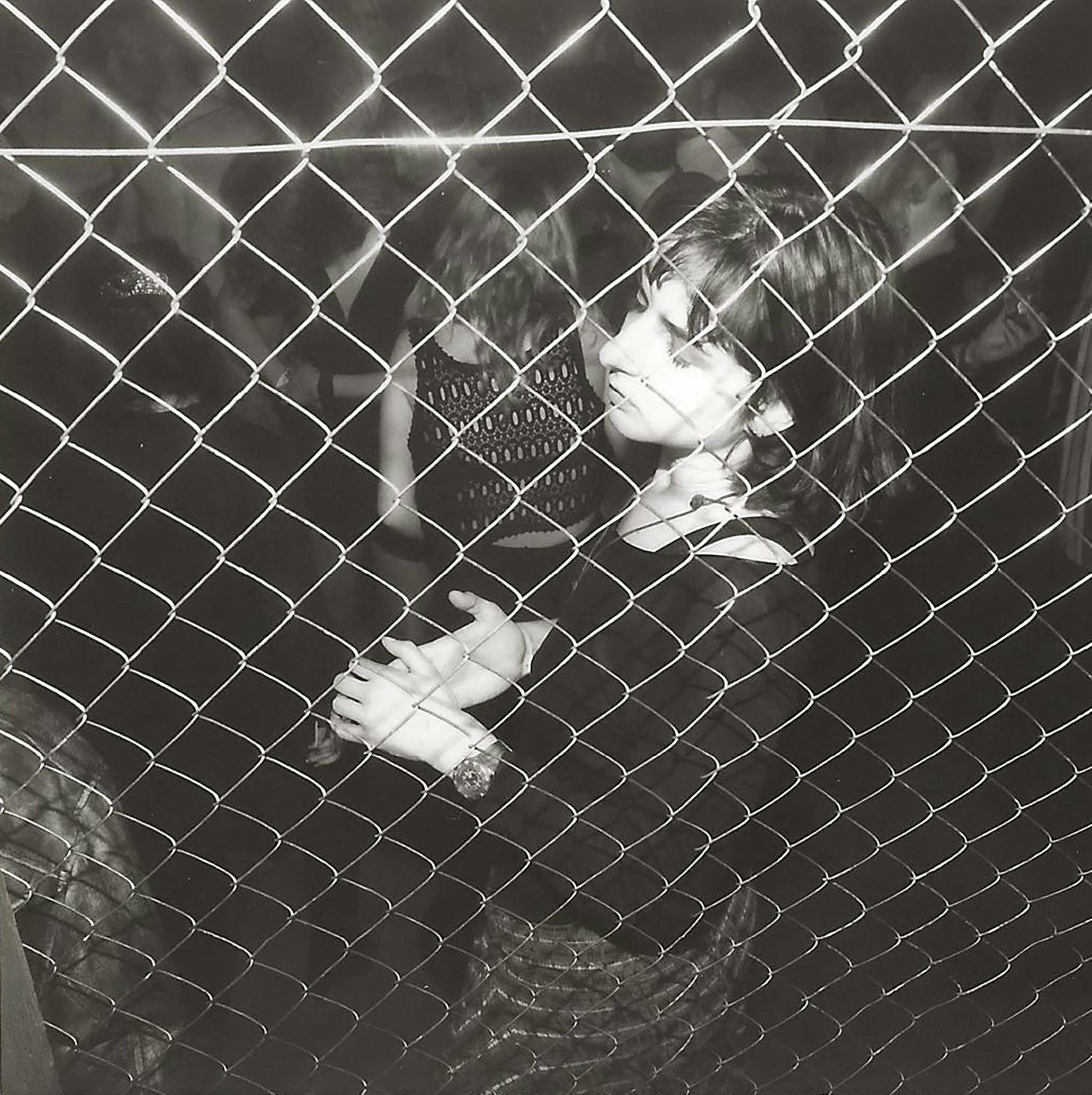

“It was unbelievable,” he says. “Hundreds of people were queuing up in front of an old factory building in the middle of nowhere between London and Brighton; you went through some dingy door and down some stairs, and suddenly you’re in this gigantic hall.”

Inside the hall he found booming music, dancing crowds, drugs, and ecstasy. The “Second Summer of Love” was the name given to the summers of 1988 and 1989 in England, seasons that left their mark on party culture. It was fascinating, remembers Gerber, but also “pretty haywire” in terms of the excessive lifestyles. “Eat, sleep, rave, repeat – that was the motto,” he says.

As the young man from Wynau was finishing his apprenticeship at Gugelmann’s, the factory was going downhill. For decades the Swiss textile industry had been in decline. Soon more and more buildings lay derelict and Gerber, who had already started playing music and organising parties in the area, thought to himself, “Well, that’s the perfect location for a rave.”

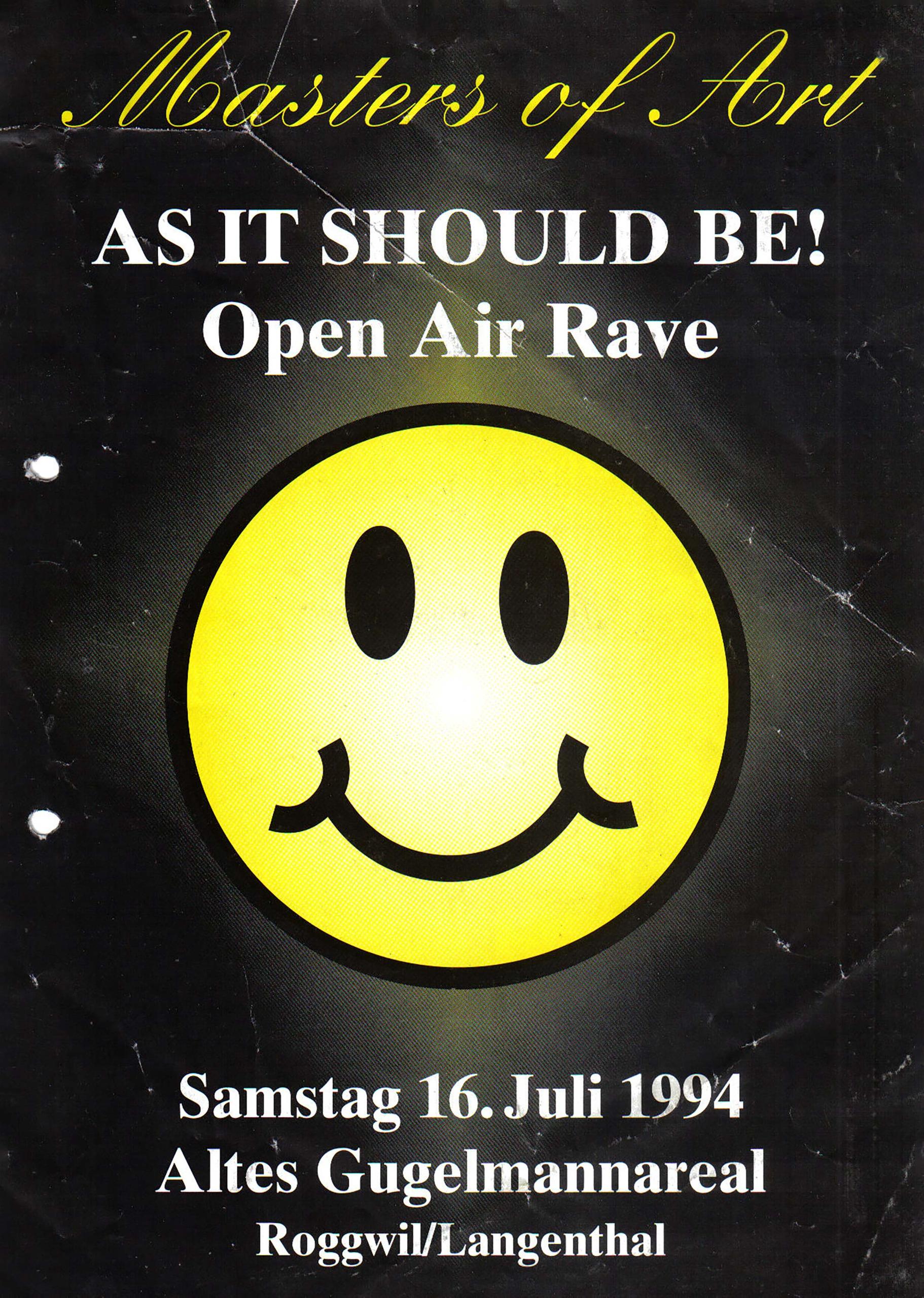

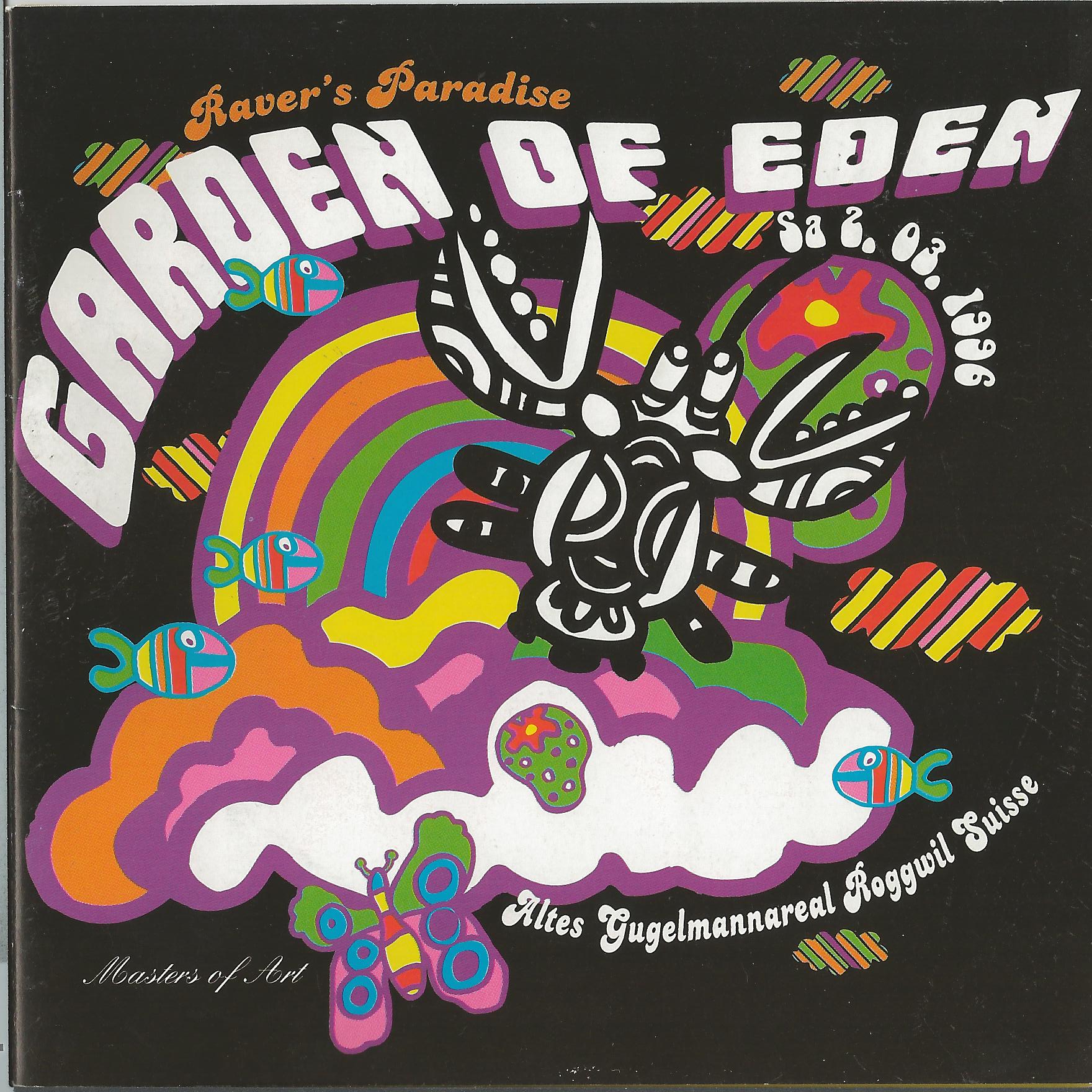

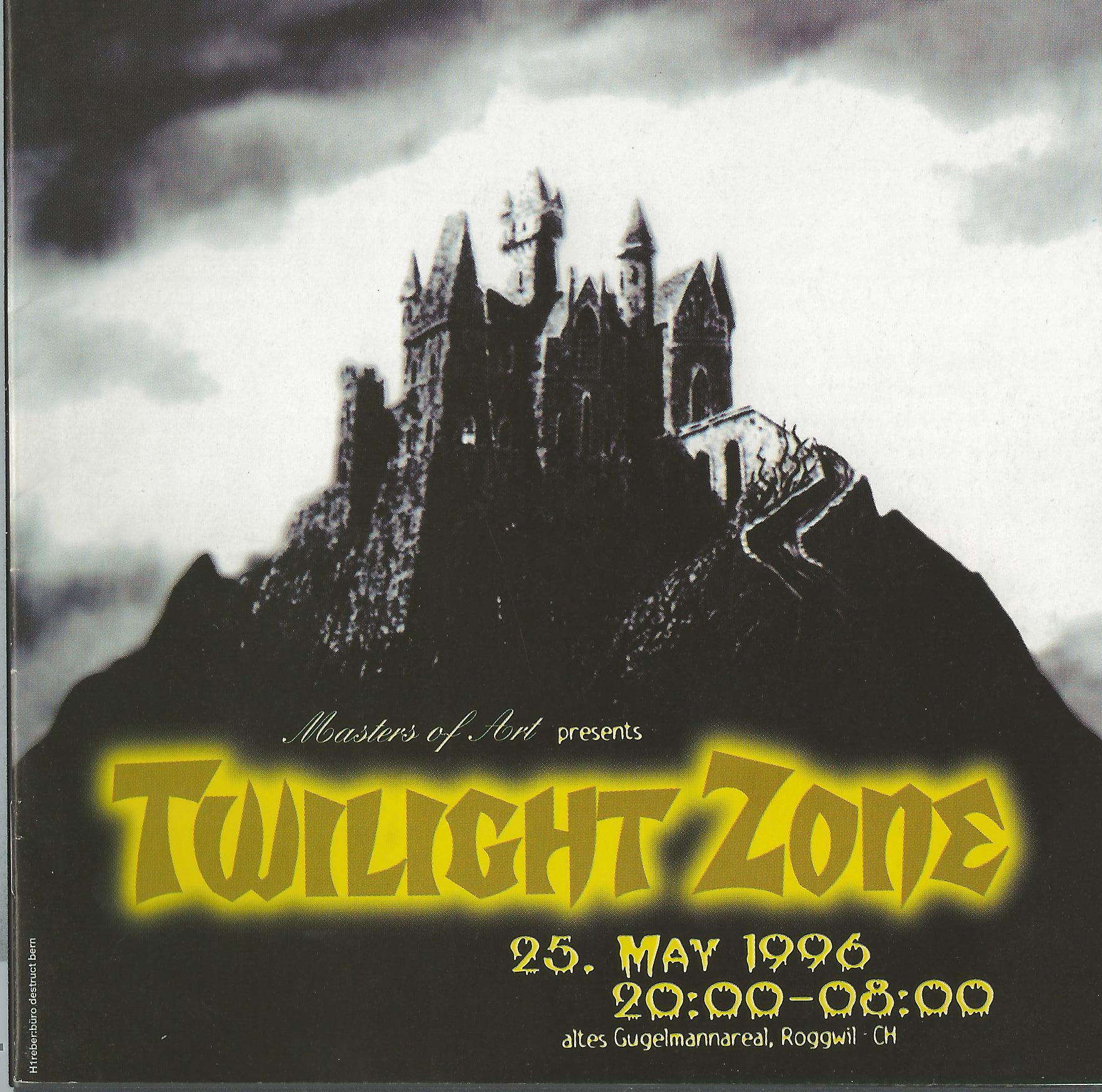

His vision quickly became reality: in May 1993 he and a friend staged the first rave in the newly abandoned textile factory. They organised everything from equipment to bookings to the bar themselves.

“Six or seven hundred people showed up at the first party, which was really a lot for Roggwil,” says Gerber.

Vibrant techno scene

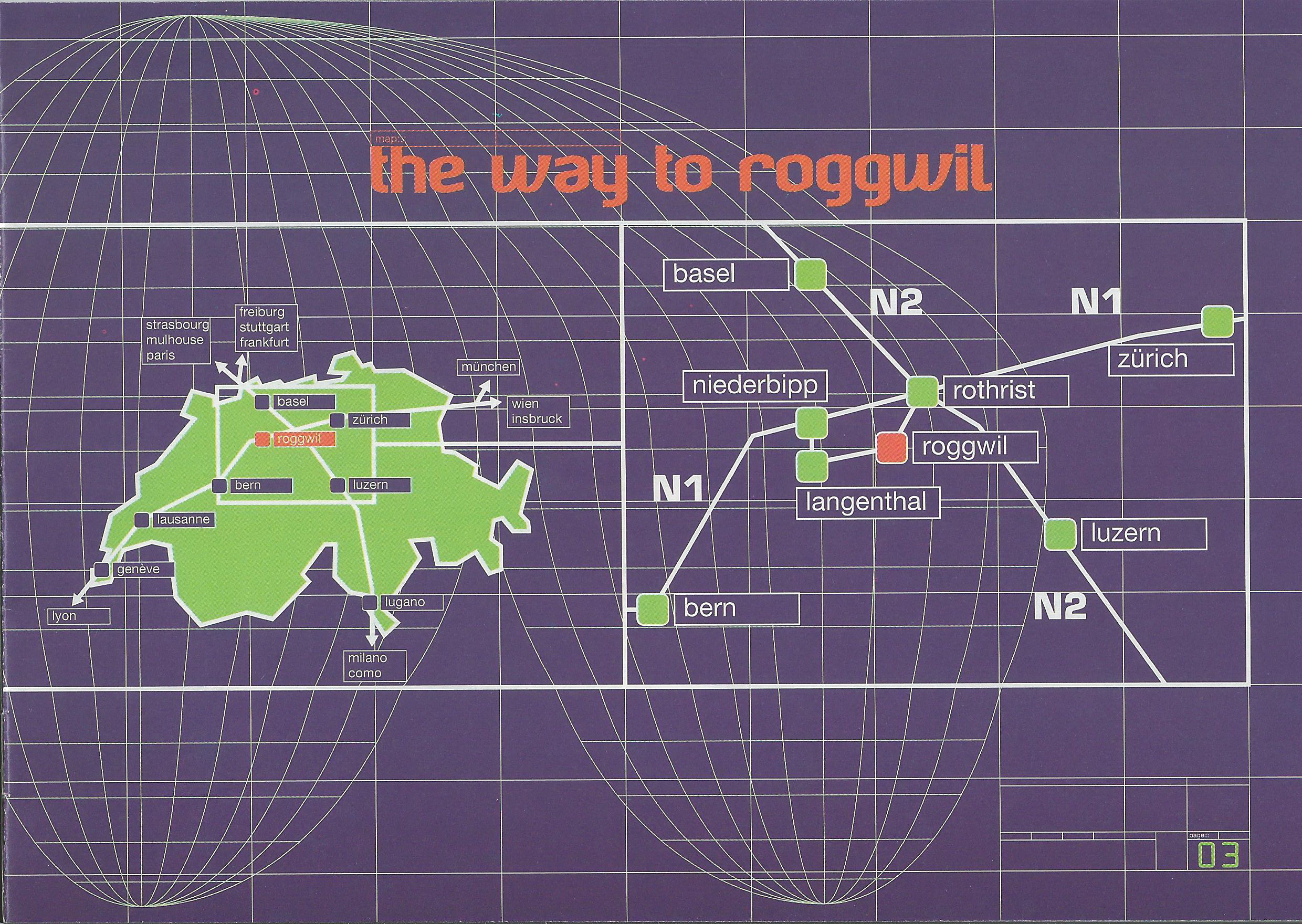

In the early 1990s the village, situated on the north-eastern boundary of canton Bern, had about 3,750 inhabitants. Boasting two railway stations, the place is unusually accessible. It is home to a couple of small businesses, has a local council dominated by the right-wing Swiss People’s Party and the left-wing Social Democratic Party, plus a vibrant culture scene of clubs and associations.

Because the factory was located in a landscape dip away from the village centre, the people of Roggwil could mostly hear the bass, but almost nobody felt annoyed by it.

“No one here had a problem with the parties,” says Annemarie Grütter. Now 63, she was part of the techno scene between 1993 and 2001 – not as a partygoer, but as a member of the local Samaritans. This deeply traditional Swiss association, with branches in many villages, offers courses in first aid. With the Samaritans, an important Roggwil association was present at the parties.

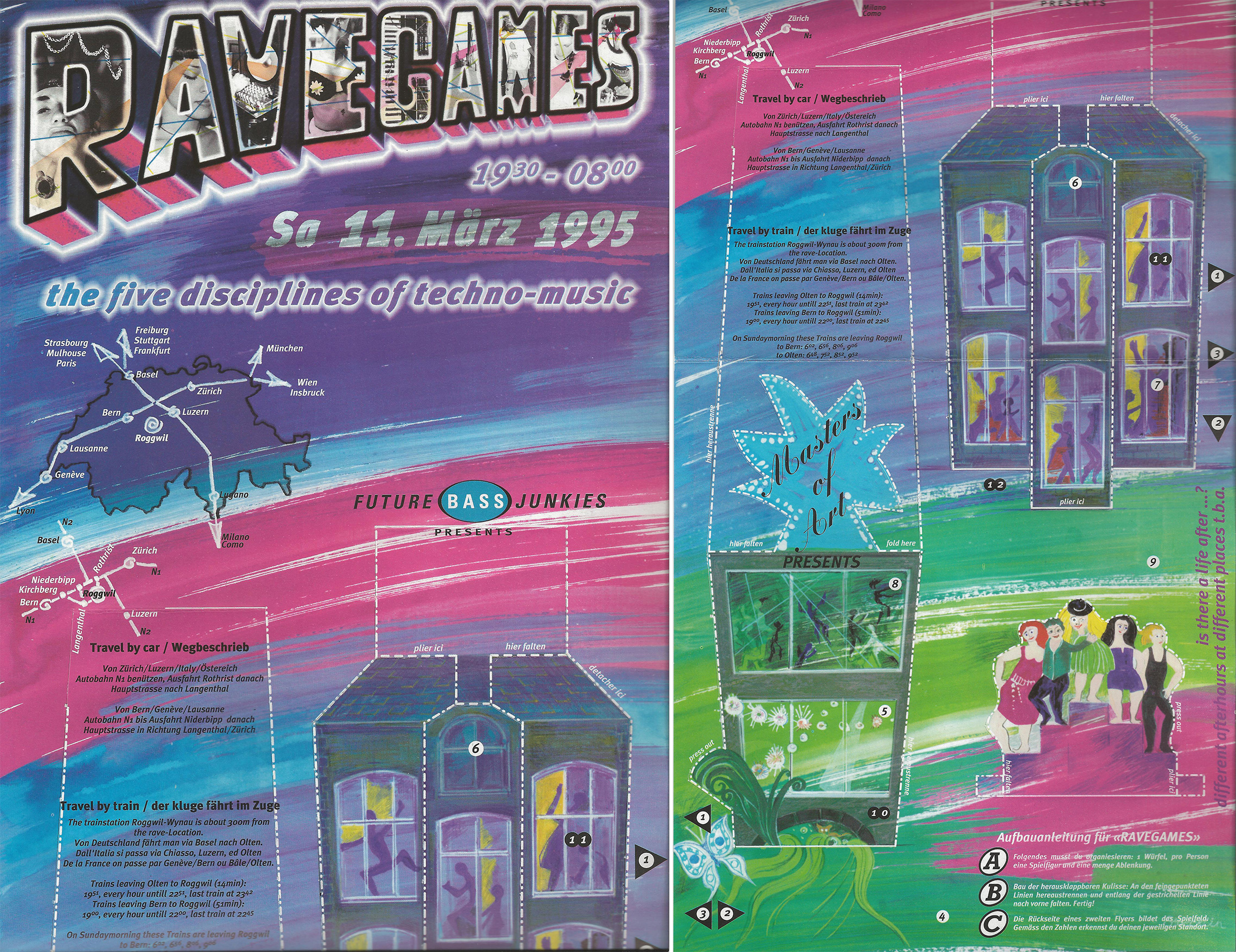

There was even a sense of pride among the inhabitants that people from all over Switzerland were converging on to their town, as various reports from Swiss public television suggest. Most of the partygoers travelled by train directly to the Roggwil-Wynau station, just a few hundred metres away from the factory halls where the raves were held. Gerber says that the father of a friend worked at Roggwil-Wynau station in the 1990s, and thanks to the parties sold tickets for the most bizarre journeys. “Roggwil–Frankfurt, Roggwil–Naples, things like that,” says Gerber.

“We probably saved the railway station from closing,” he adds.

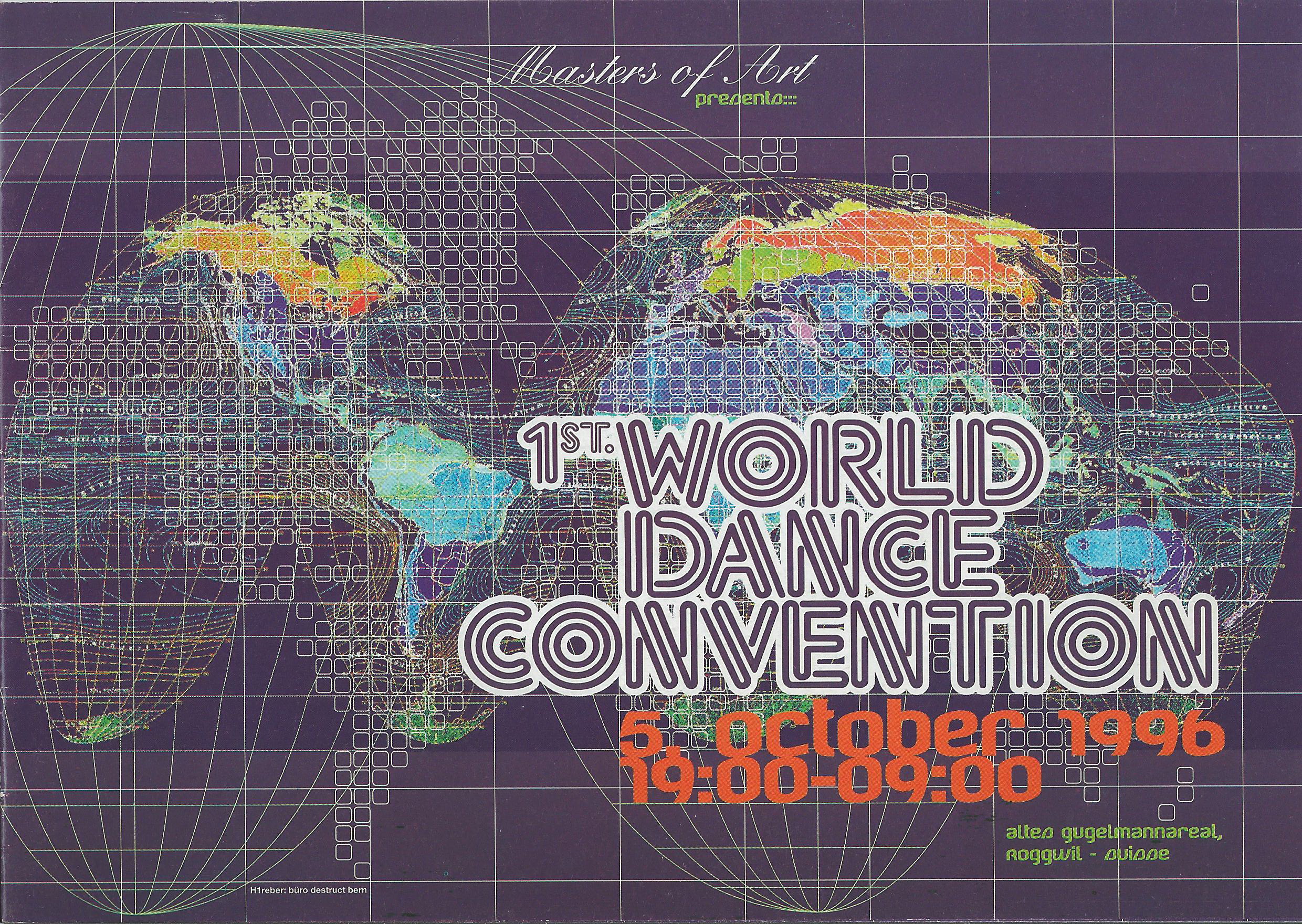

Heart of Europe

That decade the techno scene in Switzerland was one of the liveliest in the world. This had to do, amongst other things, with the country’s location at the heart of Europe, explains Bjørn Schaeffner of ClubCultureCH, an association that documents the history of Swiss nightlife. The party culture that emerged in Zurich, Montreux and other Swiss cities from 1990 onwards was closely intertwined with that of Germany, Italy and France.

“As a village, Roggwil metamorphosed into a central European rave mecca,” says Schaeffner.

Another local villager who was there from the very start is Michael Glauser (not his real name). In spring 1993, when the first big party was staged at Gugelmann’s, he was only 13 years old.

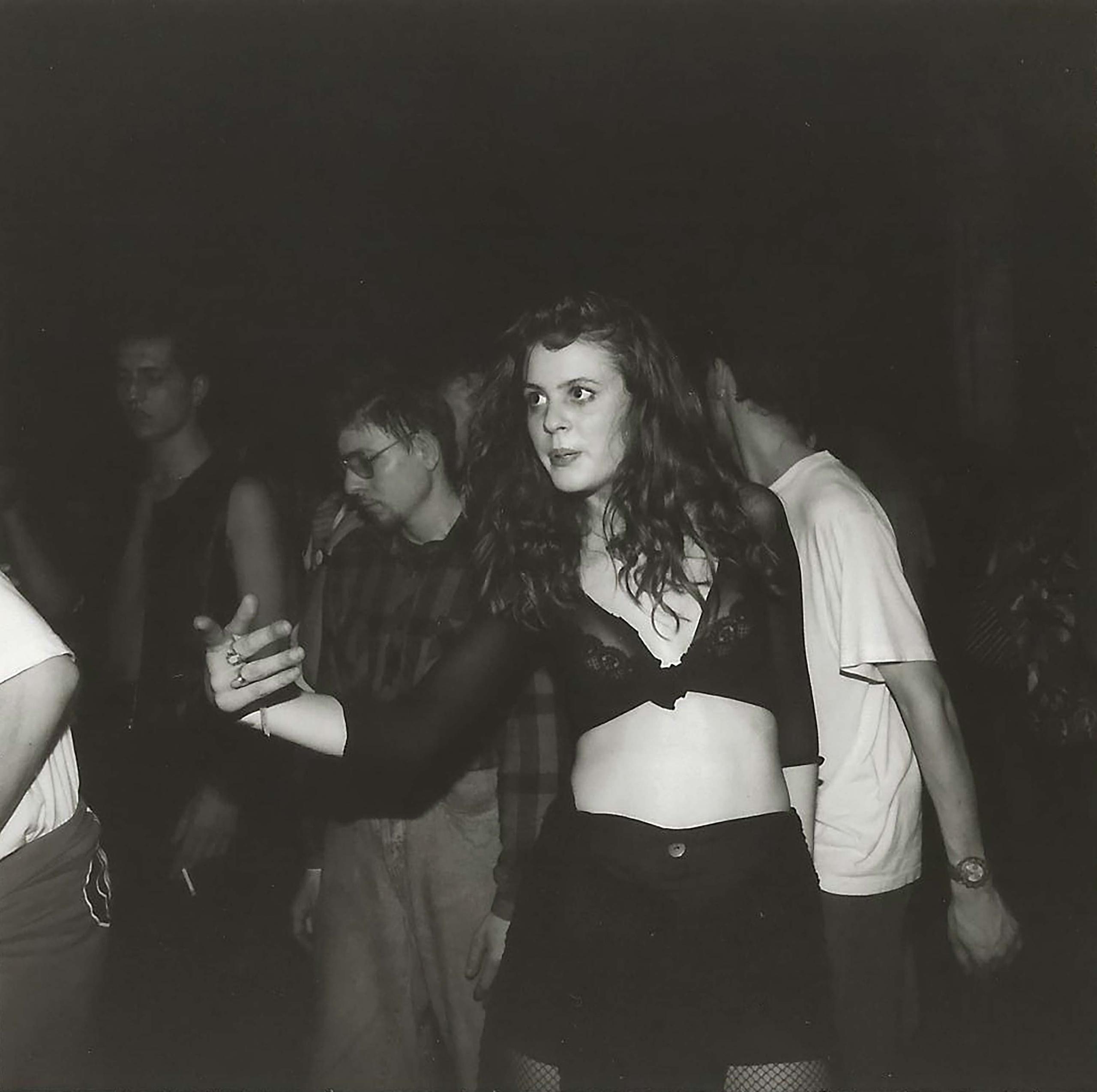

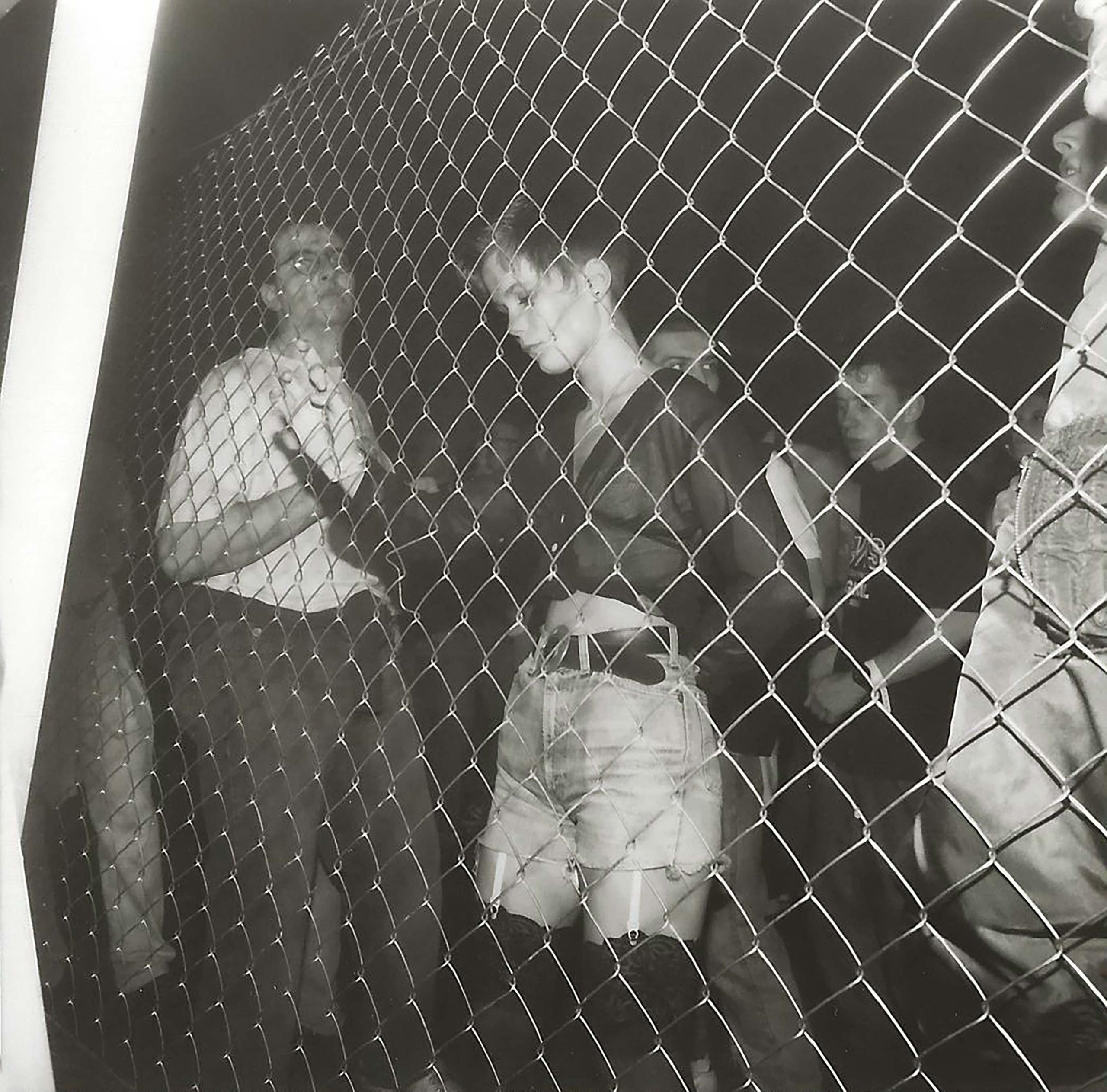

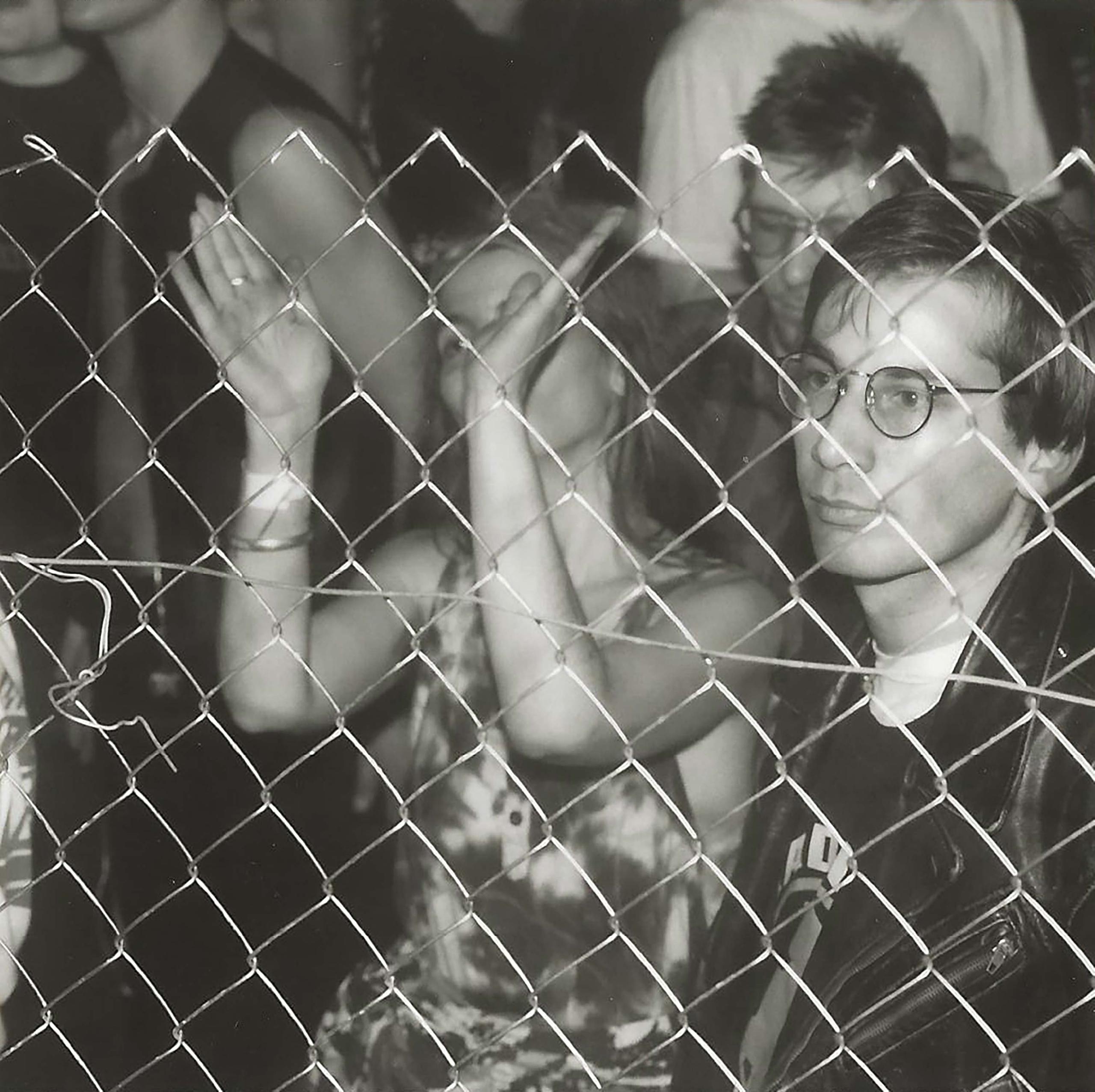

“I went there with a couple of friends,” he says. “We stood around in front of the entrance and swigged Red Bull, which was illegal back then – a guy was selling cans for CHF7 ($7) each from his car.” He watched the people in their crazy outfits: “bell-bottomed trousers, neon colours, white gloves, Buffalo shoes”. Once inside, he was fascinated.

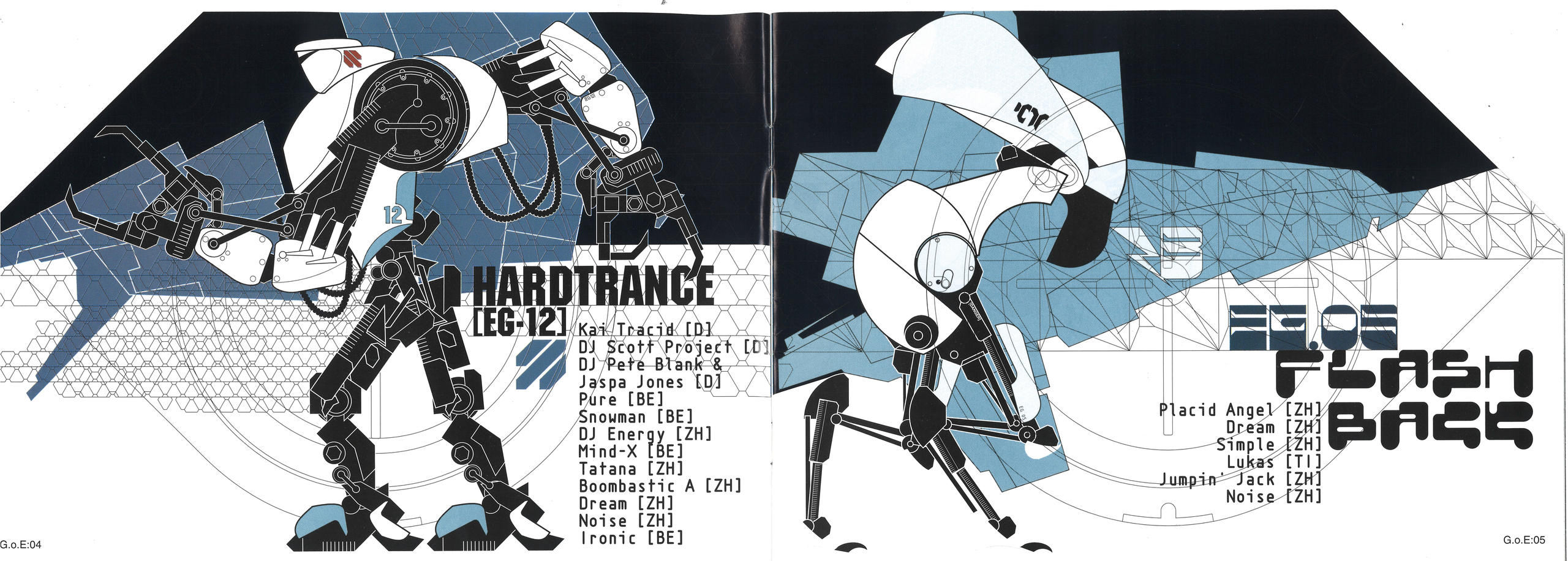

“I was hooked on it,” says Glauser. The teenager wandered through all the different halls for hours with his friends, soaking up the various musical genres: techno, house, Gabber, drum&bass, and trance.

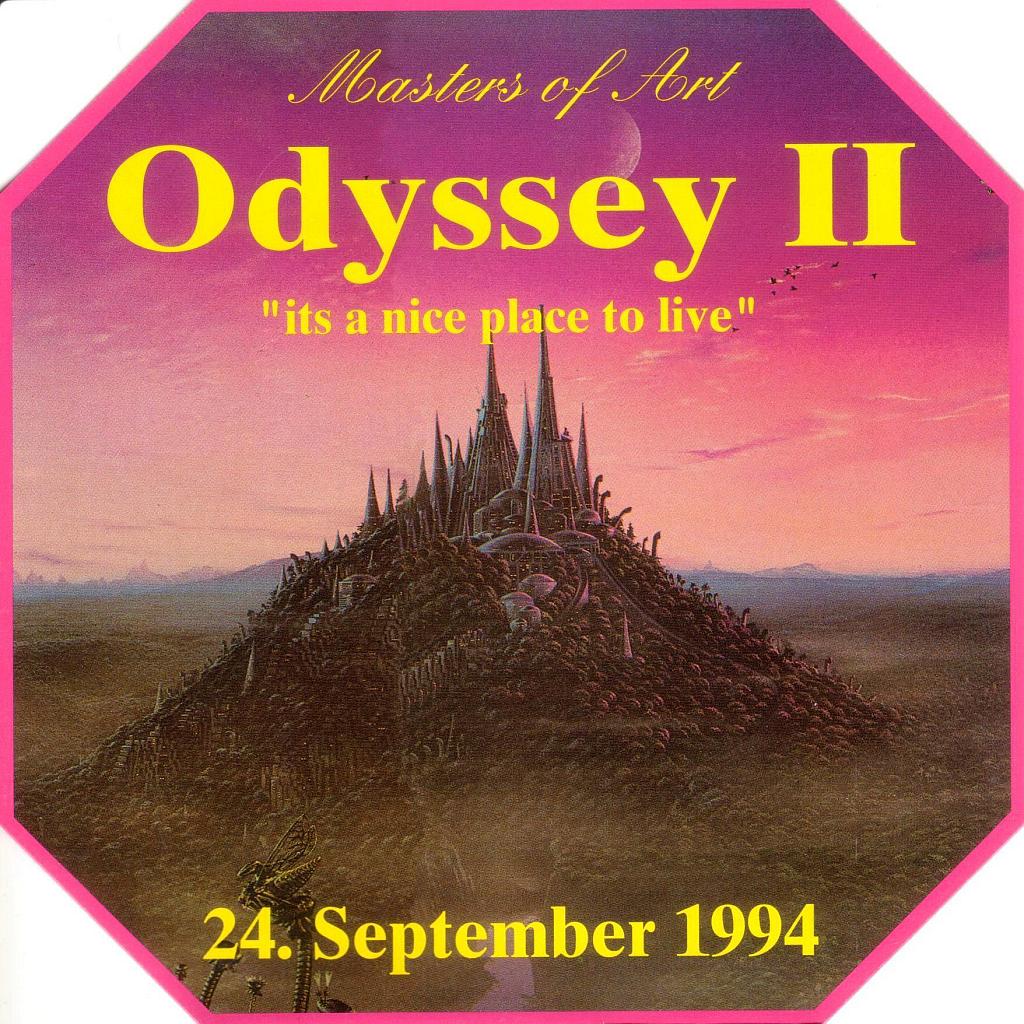

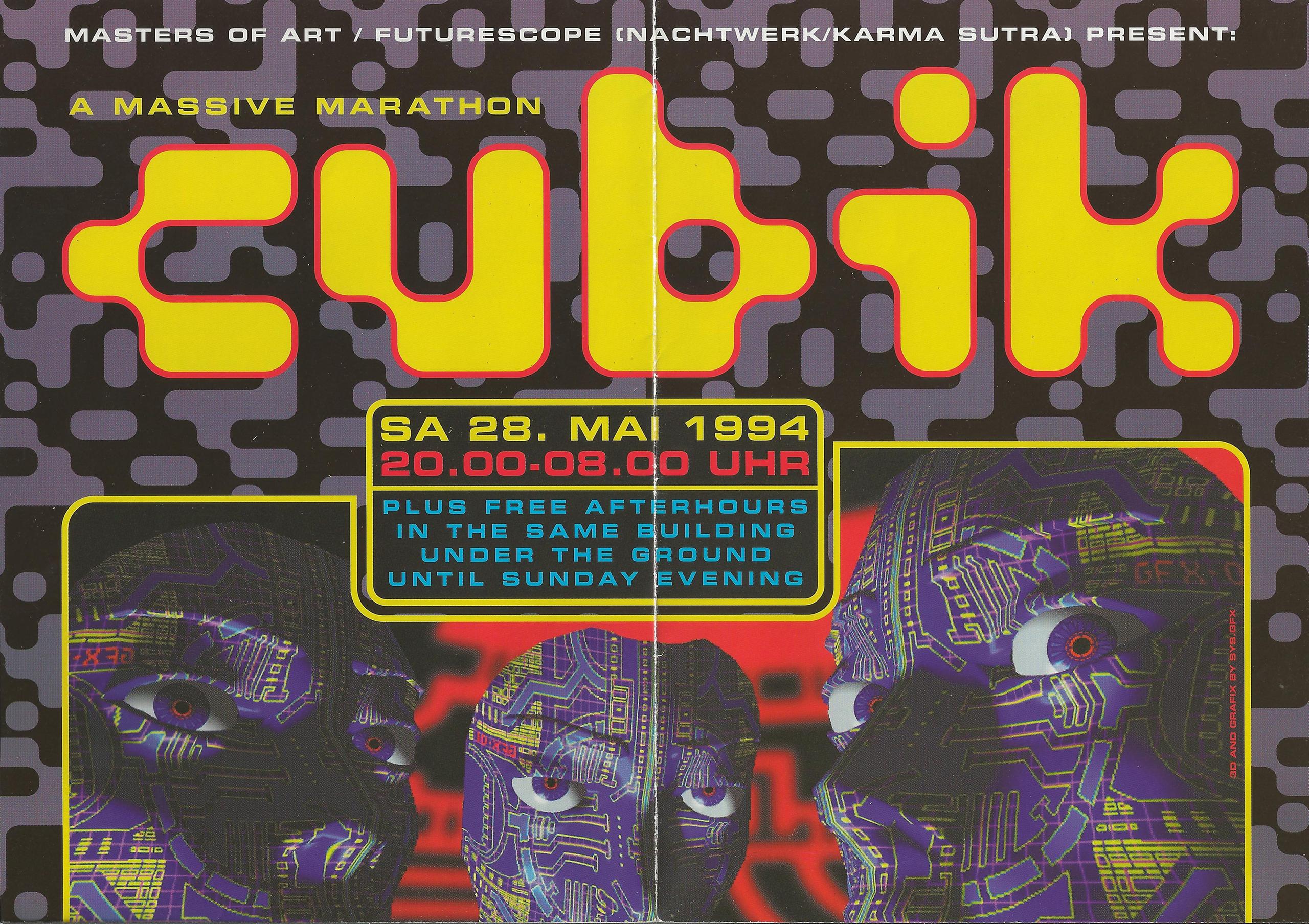

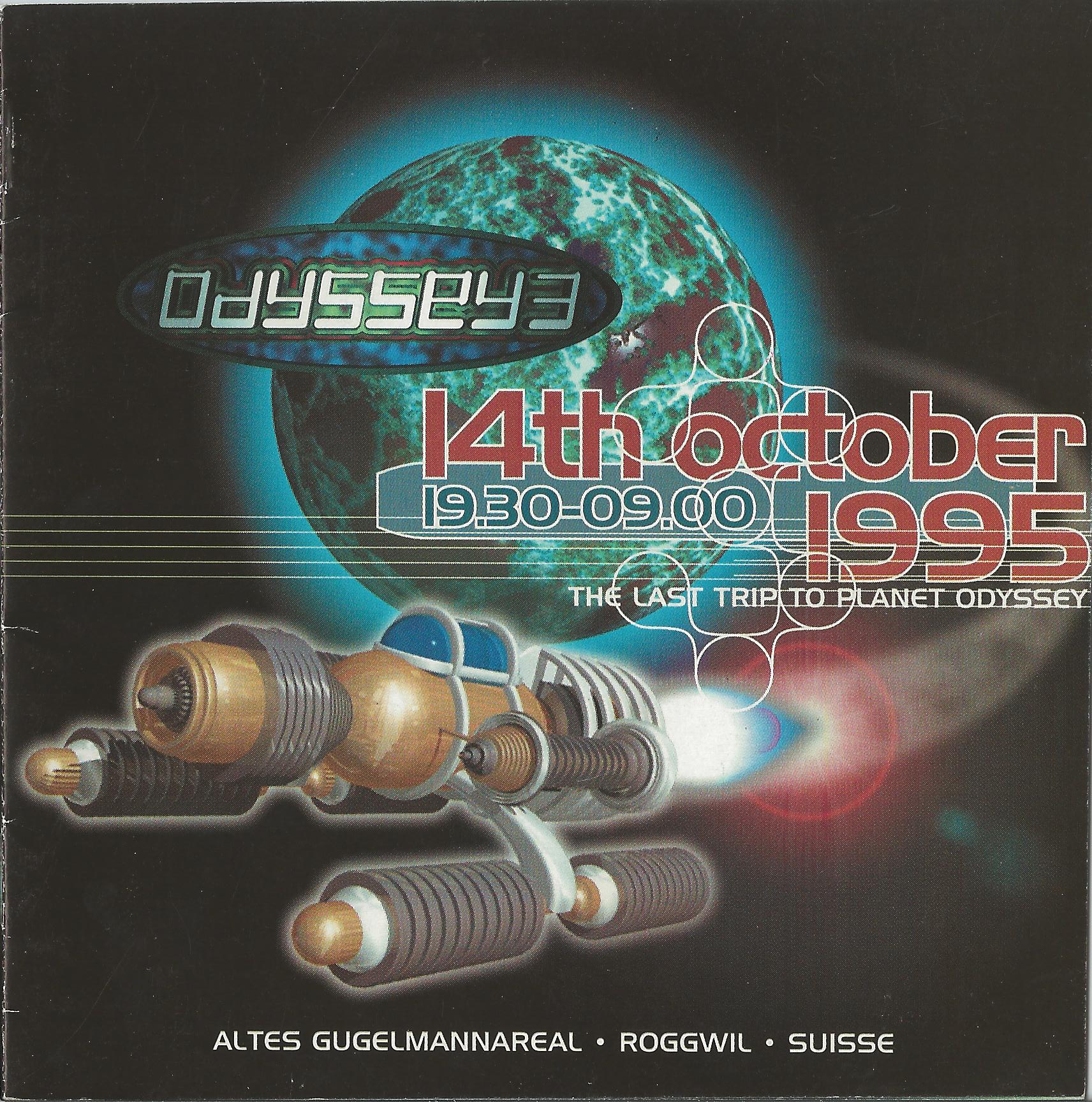

“1994 was the first big bang,” says Gerber. He and his partner were counting on about 1,000 to 1,500 people – 6,000 came. From then on things took off: more and more partygoers from across Switzerland and abroad arrived, some on special trains that ran from Zurich to Roggwil-Wynau. Then came a record: Odyssey 3 in 1995, when 13,000 rave fans crammed into the halls – with another 7,000 having to be sent home.

“It reached a dimension that slowly became scary for us,” says Gerber. There came a sense among both organisers and guests that things had reached their peak.

“It was said at the time that there wasn’t a single punch-up,” says Glauser of Cubik 95, which took place that same year. It wasn’t only because of the music and the good mood of the ravers; the drug for which the rave culture is famous – Ecstasy – also played a role.

“I downed my first pill in 1995,” says Glauser. Ecstasy, which was sold in tablet form and back then contained almost only MDMA, was famous for making its users euphoric, overflowing with love and peace. “You just want to hug everyone,” recalls Glauser. The parties were saturated with a mixture of freedom, love and togetherness; he got to know people from all over Switzerland and abroad. “It was the time of my life,” he says.

After the Euphoria

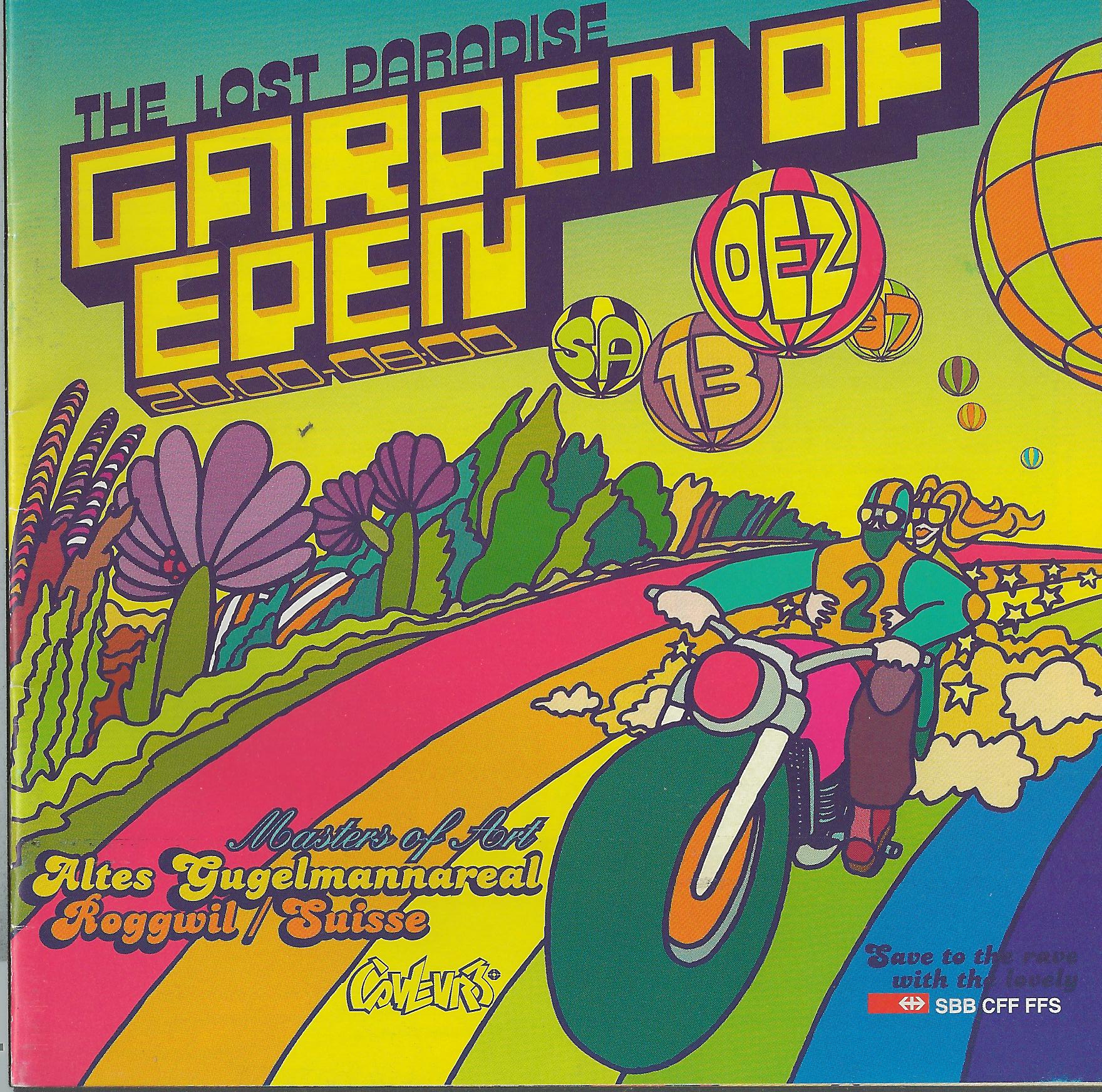

The euphoria turned out to be short-lived in Roggwil. Organiser Mirosch Gerber began experimenting with the style, in a bid to get away from mainstream techno, and tried to put together a more underground programme. But it failed: “1996 and 1997 were bad years,” says Gerber. Fewer people than expected turned up and the large financial losses caused a break.

Moreover, as the years went by the mood became less peaceful due, among other factors, to the noticeable move from Ecstasy to the use of Speed and alcohol.

“It was more legal for the guests and better for people’s pockets money-wise, but the problems associated with alcohol immediately appeared,” Gerber explains. The number of security staff had to be beefed up and the first-aid team had their hands full. It was no longer “the loving Ecstasy kids” who came.

“It sounds stupid now, but I would rather have had ten people on Ecstasy in the emergency tent, all lying there in peace, than two people as drunk as skunks and rampaging about,” says Grütter of the Samaritans.

Far-right crash the party

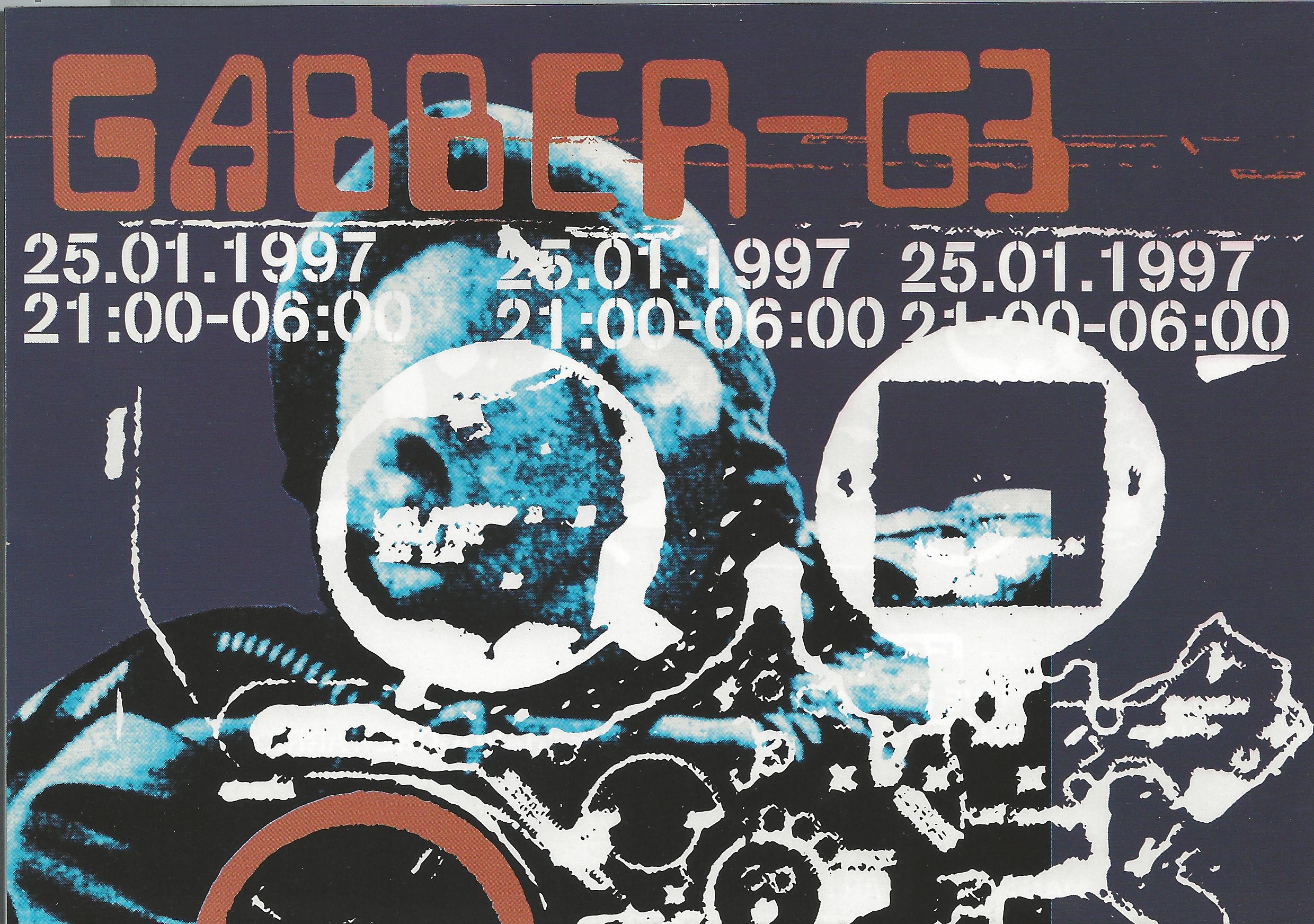

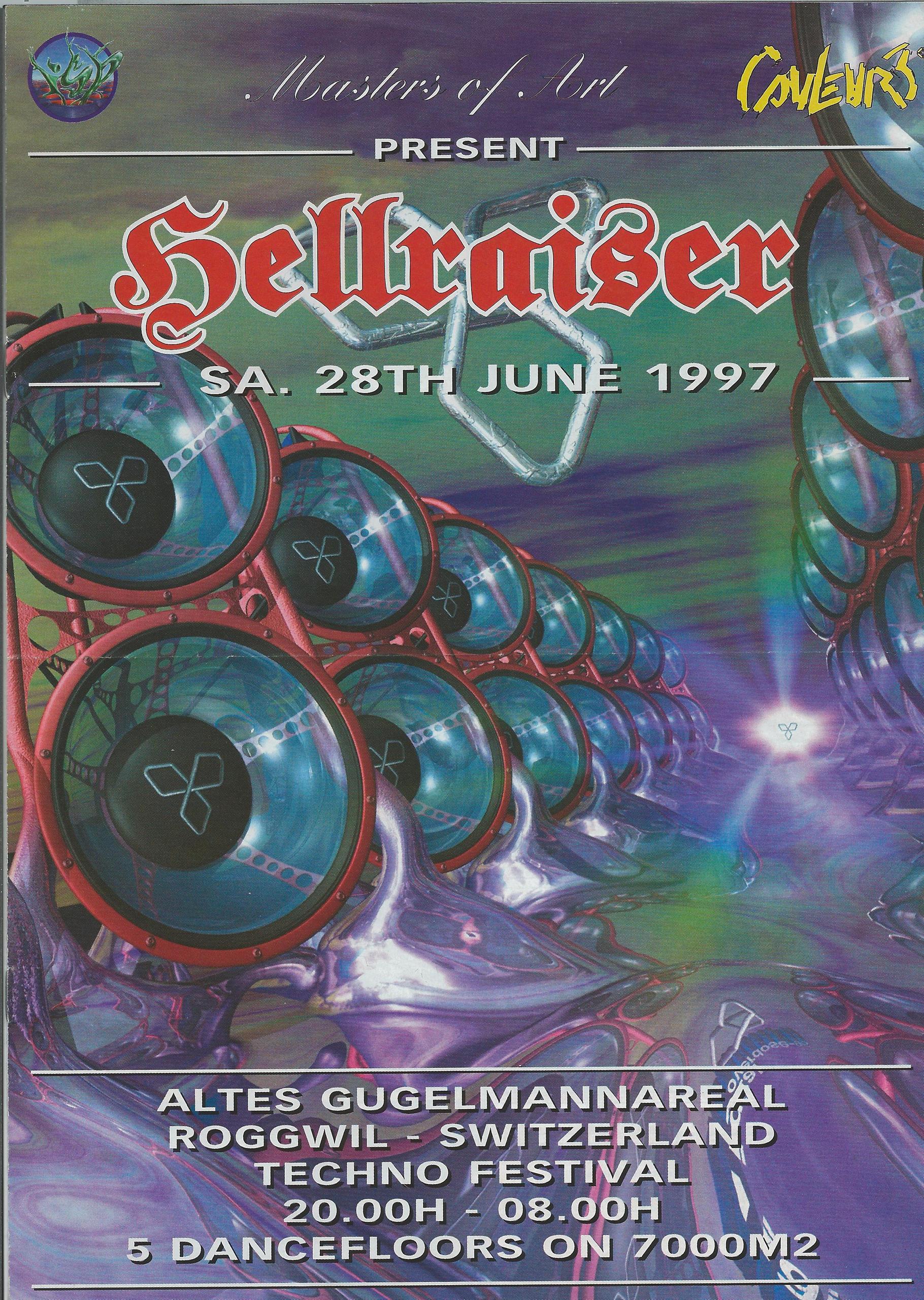

There was another reason: neo-Nazis. Some of them came from the village itself, which until the mid-2000s had a reputation as a centre of the far-right scene. Others travelled up from Rome and Northern Italy, according to Gerber.

The problem manifested itself especially on the Gabber dance floor, an extremely fast and hard form of music from Rotterdam which was quickly picked up by the far-right.

“Three-quarters of the guests on the Gabber floor were okay,” says Gerber. “But when suddenly the whole front row start saluting with their right arms, then you have to say to yourself: ‘Sorry, but what’s gone wrong here? This is definitely not the place for this.’”

To solve the problem, the organisers hired additional security staff. They also tried to attract more partygoers by refocusing on mainstream music. From 1998 onwards, Gerber had a new partner who paid “to snap up everyone with a name or fame,” as he says. “We went commercial.” It was a success. Twelve thousand people joined the first party in the Goliath series in 1998.

Memories

From this point on, it was more about business than about a dream project, admits the former organiser. The business flourished up to 2001, even though planning became more complicated: the official requirements became stricter and the owner of the site, the businessman Adrian Gasser, demanded more money to use it, says Gerber.

What remains now is an entire generation for whom Roggwil is a part of the vocabulary – and a lot of warm memories among the villagers.

“It was a beautiful time,” says Annemarie Grütter. Her association was never more closely-knit than during their shifts at the parties at Gugelmann’s. Mirosch Gerber, who today is a campaign manager at Swiss Post, also looks back fondly. He learnt a lot during that time.

“The most important business lessons that I still use now, I learnt them all back then,” he says. “You can’t learn something like that at university.”

As for the music-loving teen Glauser, the now 41-year-old managed to finish school despite the innumerable parties and drugs – which he not only consumed but also sold for a time. These days he works as an educator. But the era still sometimes catches up with him.

“Sometimes, when I’m out, I bump into another old guy who comes up to me and says, ‘Hey, we know each other from somewhere, don’t we?’” he says. “Yes,” he replies each time, “I was there – that’s why neither of us can remember any more”.

Translated from German by Thomas Skelton-Robinson/gw

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.