The next global pandemic: long-term unemployment

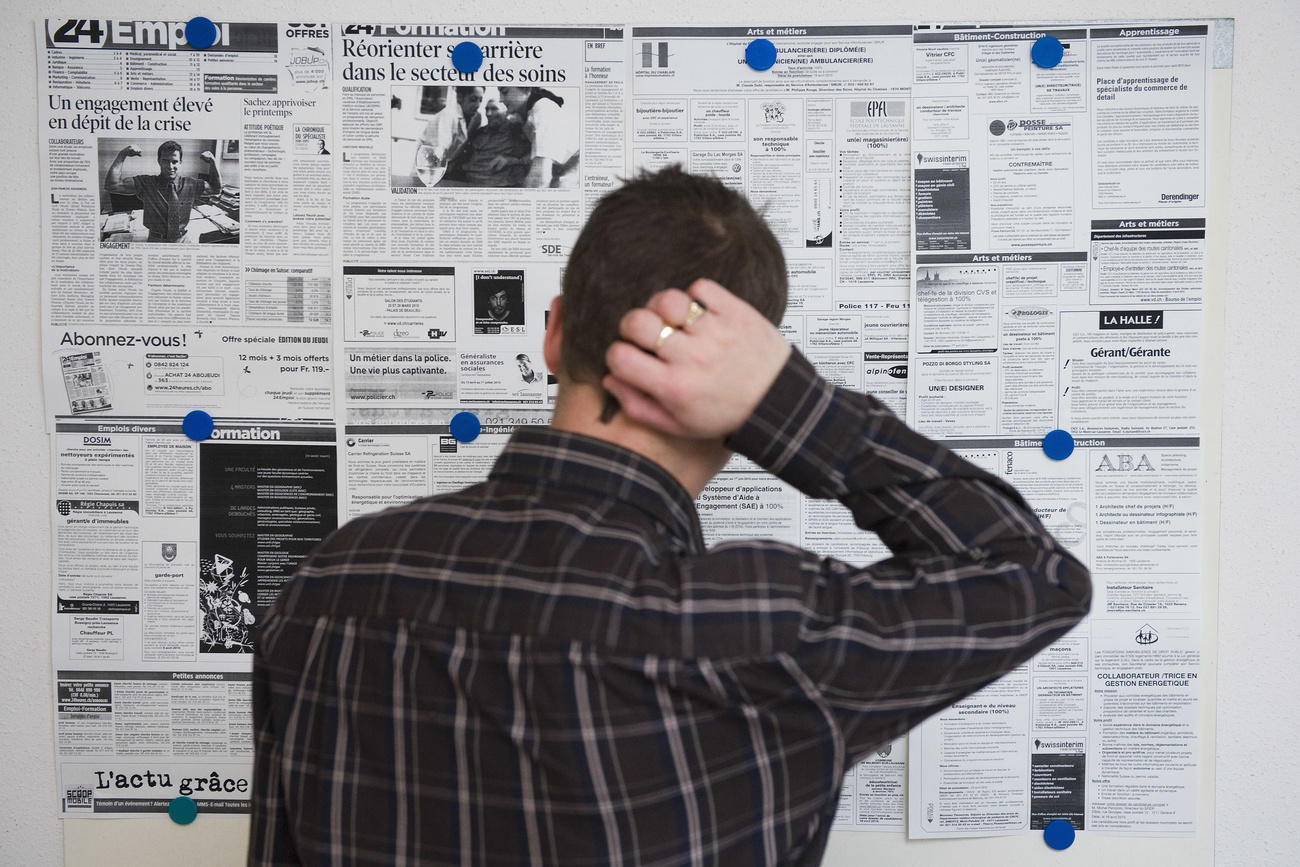

With Covid-19 hitting the job market hard, long-term unemployment figures are rising globally. Experts warn that the situation could be a ticking time-bomb.

Oliver Schopfer, an accountant in his 50s from canton Vaud (southwestern Switzerland), had been out of a job for almost a year before he finally found a position at the end of 2019. Just a month after beginning his new job, Schopfer – who has over 30 years of experience in his field – found himself out of work again.

“The company worked a lot with restaurant owners,” Schopfer recalled. “When the [Covid-19] crisis hit, they told me they couldn’t afford to pay my salary anymore.”

In Switzerland and elsewhere, governments introduced more or less strict measures in spring 2020 to fight the pandemic, effectively putting entire swathes of the economy on hold. In the context of general uncertainty that followed, many companies postponed hiring while others were immediately forced to let staff go. Retail, food and beverage, tourism and entertainment were the sectors most hit by the economic crisis.

Unemployment statistics have since progressed differently depending on the country, the structure of its labour market, the health measures implemented, and strategies put in place to safeguard jobs. But, throughout 2020, numbers rose almost everywhere.

By January 2021, the unemployment rate in Switzerland, while remaining low compared to its neighbours, had reached record levels – 5% according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO), and 3.7% according to the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), which only includes in its statistics people who are registered with regional employment centres. These centres run Switzerland’s unemployment system; they give advice and offer job openings.

With an improvement in economic outlook unlikely in the near future, worries are growing that this period of unemployment could stretch on for months or even years for certain segments of the population.

Historic high

Long-term unemployment has jumped to record highs in most countries around the world. “Long-term” unemployed is defined as those out of work longer than a year. The number of new long-term unemployed in GermanyExternal link hit 500 000 by the end of 2020. Last year, the figure jumped by 37% in AustriaExternal link and by 52% in SpainExternal link. In FranceExternal link, the situation concerns some three million people.

The United States and Canada have seen the biggest jumps in long-term unemployment. People out of work for at least six months at the end of 2020 stood at 2.8% of the American population and 2.2% of the Canadian.

In Switzerland, according to the Federal Statistical Office (FSO), 89,000 people were long-term unemployed during the fourth quarter of 2020 – that’s 22,000 more than a year earlier. The proportion of such cases in the overall jobless figures also rose.

Could be worse

Rafael Lalive, an economics professor at the University of Lausanne and at the Enterprise for Society (E4S), says these figures suggest that long-term unemployment numbers will keep rising in the next months. However, he adds, the downturn in the job market has up to now not been as severe as feared.

In Europe, one public measure in particular appears to have helped stem the tide: partial unemployment, or short-term contracts. Governments have compensated businesses who temporarily reduce the number of hours worked by employees (see box) rather than lay them off. Over 1.3 million people in Switzerland – almost a quarter of the working population – and 32 million across Europe benefitted from such mechanisms during the first wave of Covid-19 in April 2020. In November, almost 300,000 people in Switzerland were still in partial unemployment.

Such a situation might be keeping some jobs “artificially” in existence, and unemployment could spike once the measures are lifted.

In the USExternal link and in CanadaExternal link, where no such measures exist, long-term unemployment numbers are nearing records last recorded during the 2010 recession. Of these, a certain number know that they will be contacted once their employer starts hiring again,” said Lalive.

During an economic crisis, when a business faces a downturn in demand, it can – as long as the staff concerned are in agreement – reduce working hours. In these cases, the employees will receive benefits from the state amounting to 80% of revenue loss. For instance, if the employer reduced the work rate from 100% to 50% for an employee, the business would pay half of the salary, the unemployment insurance would pay 80% of the other half, and the employee would end up with 90% of his or her initial salary

The spectre of exclusion

For some, the current situation is a phase that will pass when the economic outlook brightens. But others face a lasting period out of a job. Long-term unemployment figures are the last to improve after a recovery begins, Lalive says.

Studies have shownExternal link that those out of work for a long time have correspondingly worse chances of finding a job. And the current situation makes things even more complicated, since low-wage and low-qualified positions, normally a way to gain a foothold in the job market, “are today the most difficult to find, since many such jobs have been cut”, explained Benoît Gaillard, co-director of communications and campaigning with the Swiss Federation of Trade Unions.

In the long run, unemployment can have serious material and psychological consequences. Social welfare beneficiaries also run the risk of increasing, as do situations where people are excluded from society.

The trade union federation is worried that inequalities will deepen between those who have been only slightly affected by the crisis and those who will be pushed out of the job market for a lasting period. Many of the latter will also have gone through financial hardship, since they are already often on low wages. “We could have people who will carry the deep scars of this period for a long time,” Gaillard said.

Olivier Schopfer, the unemployed accountant from canton Vaud, is optimistic he will find work soon and that the virus is just a setback. “Of course rejection to applications can get me down, but I’m not getting beaten up about it. I just take things as they come”, he said. His unemployment benefits have been extended and he is currently working on a reinsertion plan with an organisation.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.