The world’s first space ‘garbage truck’ will be Swiss

It is the first time the European Space Agency (ESA) has allocated such a large sum (€86 million) to a start-up. It's Swiss and its mission is to clean up space debris.

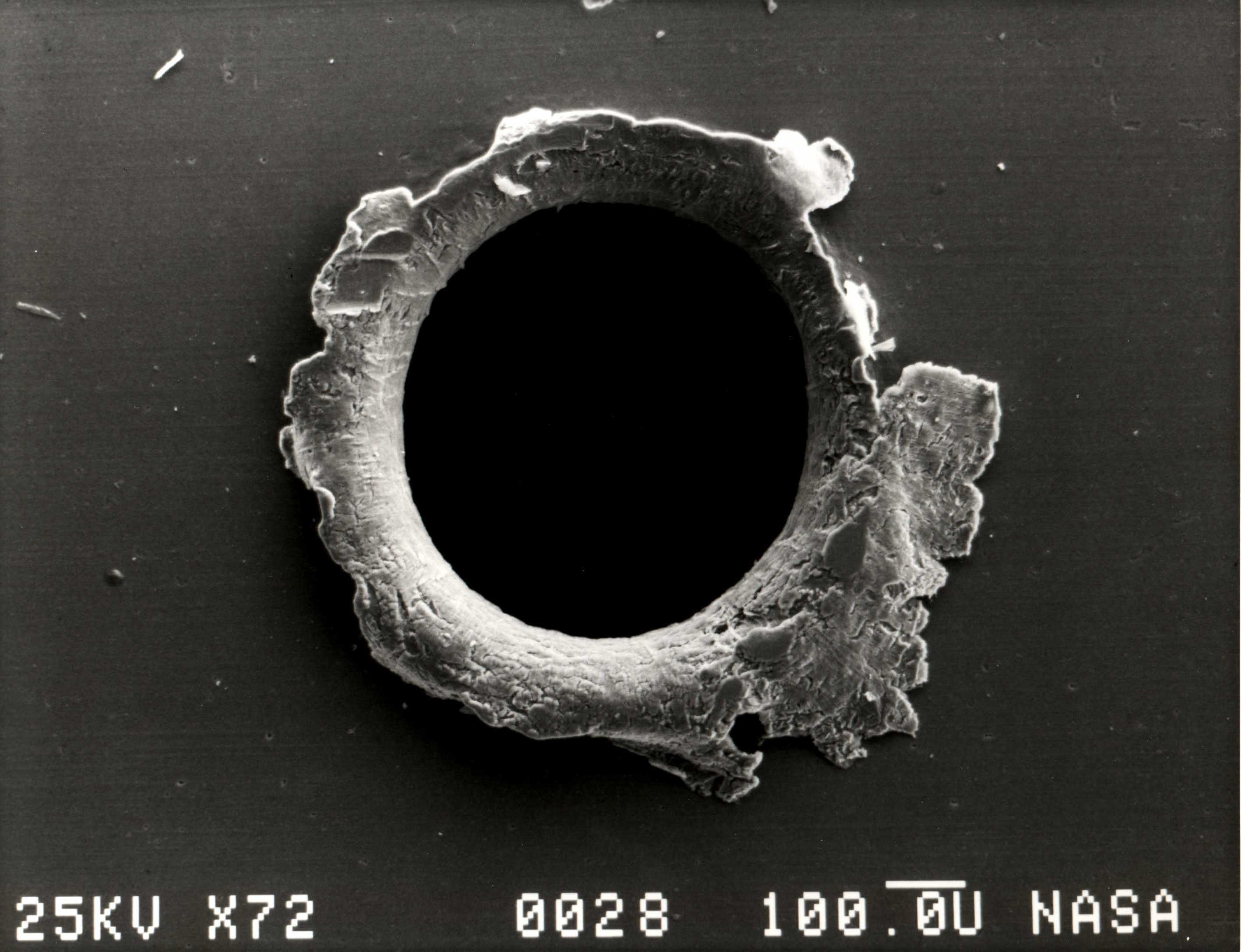

February 10, 2009, 4.56pm GMT: The American commercial satellite Iridium 33 collides with the Russian military satellite Kosmos 2251 at a speed of almost 42,000 km/h. The two spacecraft disintegrate into more than 600 pieces of scrap metal, which scatter at 20 times the speed of a rifle bullet.

This is the first recorded accident of this kind, but by no means the only one. Some of them are even intentional: the Russians, the Americans, the Chinese and the Indians have all destroyed one or more of their own satellites to test space missiles. And these explosions have created thousands of additional pieces of debris that could damage any orbiting spacecraft – including the International Space Station. This is the scenario screenwriter and film director Alfonso Cuarón depicted at the beginning of his film Gravity.

An idea was born

Back in 2009, Muriel Richard-Noca and her students at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL) were celebrating the launch of the SwissCube mini satellite, which they built together. And while the first 100% Swiss-made space orbiter is no bigger than a carton of milk, the space engineer was already thinking about when it would become a piece of space junk. After all, SwissCube was programmed to pass close to the area where the Iridium and Kosmos satellites collided a few months earlier. The debris from that collision was still moving around in space.

In 2012, in response to the dangers posed by space debris to SwissCube, Richard-Noca and the EPFL Space Center launched a space clean-up project, known as CleanSpace. At the same time but independently, Luisa Innocenti, a physicist at ESA, convinced the agency to launch a programme, which it also named CleanSpace.

Special project

Eight years later, the EPFL initiative became a start-up, renamed ClearSpace. And as already announced in autumn 2019, it was chosen by ESA from among 13 candidates – including several European industrial giants – to do the job. The start-up has just increased its workforce from five to 20 people.

This is the first time that ESA has purchased an end-to-end service contract rather than operating the mission itself. More importantly, it is the first time that a space agency has ever committed such a large sum of money to a start-up. ESA will provide €86 million (CHF93 million), with ClearSpace responsible for finding the €24 million (CHF26 million) needed to complete the budget.

But as was pointed out during this week’s online press conference, ClearSpace is much more than a start-up. The company has spent the past year bringing together a consortium of institutes and industries from eight European countries, including giants such as Airbus and Switzerland’s arms maker RUAG – which, among other things, builds the payload fairings of the Ariane rockets. Thus while the ClearSpace-1 satellite still exists only on paper, its construction will be carried out by experienced firms. ESA will also carry out the necessary checks before each instalment of funding is paid out.

Many unknowns

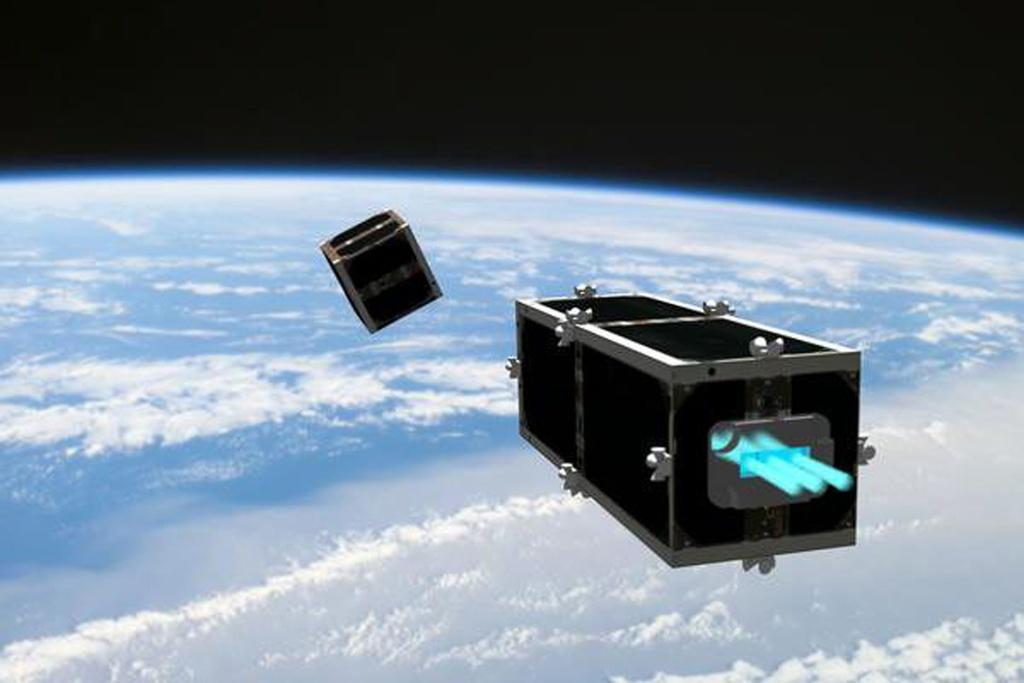

ClearSpace-1 is scheduled to take off in 2025 on board the European Vega rocket. Its mission is to capture space debris and then place itself in a re-entry orbit with the space junk. Friction will cause the captured debris and ClearSpace-1 to burn up, leaving space a tiny bit cleaner and safer.

The chosen target is a VESPA. It has nothing to do with the famous Italian scooter, although it is not much bigger or heavier – 112 kilogrammes (246 lbs). The VEga Secondary Payload Adapter (VESPA) is a small metal cone that is used to separate satellites from each other when they are carried by the same rocket. It was launched in 2013 by a Vega rocket in a low orbit of 800 km from Earth.

However, no one has ever captured an “uncooperative” object in space. The VESPA, which moves freely by turning on itself, has no operator or engine.

“We’ve all seen in movies an astronaut who, when trying to catch a tool, makes a false move and the tool disappears into space like a flying golf ball. It is exactly the same with the VESPA,” says Innocenti. ClearSpace-1 will have to open its four arms wide to smoothly capture the object.

Another difficulty is the Sun, which blinds the cameras and could make the target invisible at the crucial moment. The “debris hunter” will therefore have to move forward step by step and constantly re-calibrate each movement with the help of artificial intelligence. And if the capture is successful, ClearSpace-1 will have to deal with a completely new object, whose dynamics will have to be understood before deciding where and how to drop it.

More than a cleaner

In the end, ClearSpace-1 will burn up with its captured debris in the upper atmosphere. That seems like an awful lot of money to pay to get rid of a single piece of space junk. Not according to the ESA and ClearSpace.

The 2025 mission should be the first in a long series, with the prospect of developing a spacecraft capable of disposing of several orbiting objects at a time. There is already talk of five or even ten pieces of debris being destroyed in a single mission.

And there’s more: ClearSpace’s technologies could also be used to refuel or make repairs to extend the life of some satellites. In the longer term, there are also plans to assemble spacecraft in orbit for long-distance travel that would be far too heavy to escape the Earth’s gravitational pull in one piece.

“Our goal is to offer low-cost and sustainable in-orbit services,” says Luc Piguet, director of ClearSpace. He estimates a potential market that could one day be worth “between a few hundred million and several billion dollars a year”.

Unclear responsibilities

Who is responsible for space debris and who pays for its disposal? The Space Treaties adopted by the United Nations in 2002 speak only of the responsibility of states in the event of an accident and say nothing about the role of private actors. Does that mean the debris is nobody’s business?

Not quite. There is a difference between old and new (or future) debris. Now very precise rules exist that space agencies and private entities must follow, even if they are not legally binding. A satellite launcher, for example, must plan to re-enter the atmosphere after 25 years and carry enough fuel to manage the manoeuvre itself.

As Piguet points out, “we are launching more and more satellites. Since 2010, the number of objects in orbit has increased 16-fold”. This phenomenon is mainly due to satellite internet constellations, such as Starlink from SpaceX or OneWeb. But these players are “very aware of the problem and very proactive”, says the boss of ClearSpace.

So the big problem is the old debris. And Piguet is adamant that “it’s now or never!”

“There are discussions at the United Nations to introduce a tax on launches, which would be used to fund a space clean-up fund to be managed by the UN,” says Innocenti. “But these are discussions between diplomats. It’s a bit like global warming, we feel like we’ve got all the time in the world, so we’re moving very slowly.”

More

In space exploration, Switzerland punches above its weight

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

Join the conversation!