Theatre director Milo Rau, the friendly revolutionary

Milo Rau is probably the most famous Swiss theatre director in the world. What is the secret of his success? SWI swissinfo.ch profiles the controversial polymath before the start of his staging of Wilhelm Tell at the Zurich’s Schauspielhaus theatre.

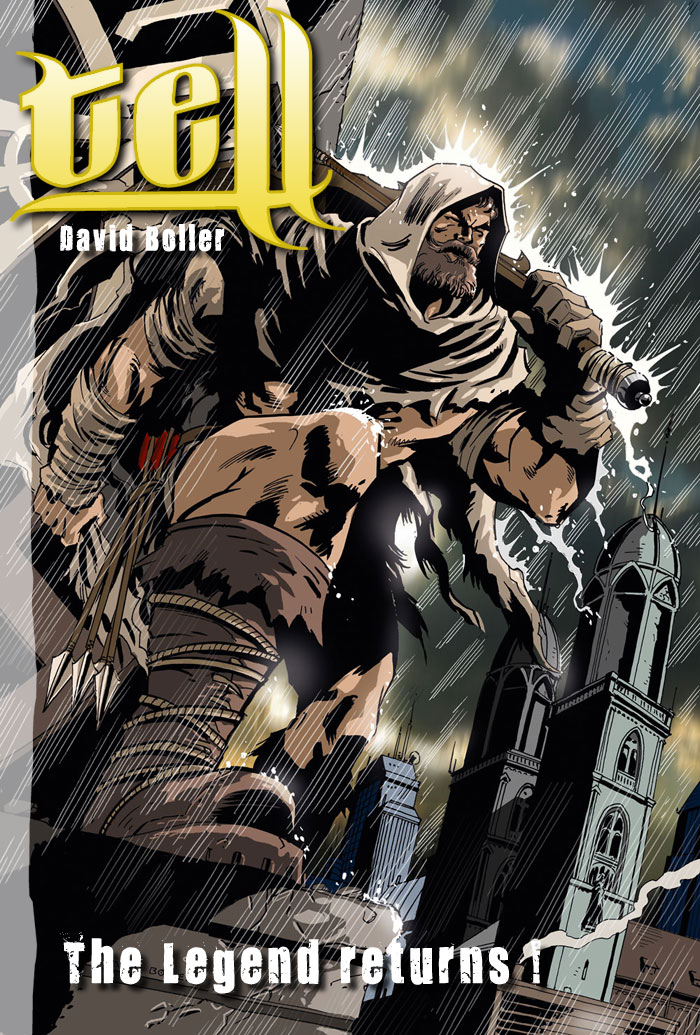

“Just ring sometime in the morning,” Rau wrote in an email. He is currently rehearsing his versionExternal link of Friedrich Schiller’s play about Swiss folk hero William Tell, which has its premiere on Saturday.

Rau’s main job is as director of the Nederlands Toneel Gent (NTGent) in Belgium, but he also writes columns and books, teaches at art colleges, and makes films. His travels have taken him to Iraq, Syria, Greece, Italy and Brazil, but also to his old home country, Switzerland. What’s more, he has two children. But time to talk at short notice? No problem.

When I spontaneously call him the next day, he answers despite standing on the rehearsal stage. “Oh! We’re just swinging an axe around; I’ll ring you back.” Beep, beep, beep. Thirty minutes later the phone rings – and Rau gets going.

His play is about left-wing and right-wing concepts of freedom, he says. For instance the freedom of the Jewish Swiss artist Miriam Cahn, who, following the debate about the Bührle Collection in the Zurich museum of art (Emil Bührle made his fortune by selling arms to Germany during the Second World War), no longer wanted her pictures housed there. It’s about current topics that are meant as triggers. And, as so often in Rau’s theatre pieces, laypeople appear on stage alongside the professional actors.

One of the professionals is Sebastian Rudolph, who is dressed up as a Nazi. Around 20 years ago he wore the same costume on the same stage for German theatre director Christoph Schlingensief when he staged Hamlet. Schlingensief invited right-wing extremists, who were apparently ready to quit the scene, to take part. The scandal was enormous.

Asked what this Nazi-Schlingensief reference has to do with Tell, Rau turns cryptic. “There are two legendary theatre productions at the Schauspielhaus Zurich,” he says. “Schlingensief’s 2001 Hamlet and Wilhelm Tell from 1939 with Heinrich Gretler in the lead role. Both productions make a reappearance in our Tell.”

More

How a Zurich theatre became an anti-fascist refuge

What interests Rau in Tell is precisely the opposite of the revolutionary who established justice for all; instead it’s the reformer who first and foremost wanted to save his own skin. And that’s where the two historical Zurich theatre pieces match the material well.

The Zurich Tell of 1939 is considered a product of intellectual national defence at a time when the Schauspielhaus, denounced by the right as a “Jew and Communist theatre”, used the popular folk-actor Heinrich Gretler to try to make a patriotic statement. This Tell had to have a Helvetic flavour. There’s no way he could have been played by a Nazi-persecuted Communist, for example Wolfgang Langhoff, who, like many other German migrants, found refuge in the Schauspielhaus Zurich.

Schlingensief’s Hamlet wanted to test the limits of the city’s liberalism: the outcry erupted in Zurich exactly when a German wanted to treat a supposedly German problem (neo-Nazis) in Switzerland. While Schlingensief stoked xenophobia among the middle-class public, Wilhelm Tell, on the eve of the Second World, tried to envelop them in patriotism.

Changing lives

Rau is also very attached to the films documenting his international achievements. He sends a link to his most recent film, The New Gospel, which premiered in September 2020 at the Venice International Film Festival. It was shown in a hundred cinemas and can now be watched on streaming platformsExternal link.

He has often turned theatre projects into films, but this contemporary crucifixion story was always originally planned as a film. In it he follows the tracks of Pier Paolo Pasolini, who filmed the material in 1964 in the same small town, Matera in southern Italy. Sixty years ago Matera still looked as though it was in the Middle Ages – even older if one looks at the hillside caves.

The stars in The New Gospel are African field labourers without identity papers. The film presents the Passion against a contemporary backdrop: a black Jesus leads a revolt on a south Italian plantation and – as we know from the story – dies for our sins.

The aim of Rau’s art is anything but modest: to change lives. Not so much those of the audience, rather those of the participants, since many of the undocumented agricultural and sex workers were afterwards granted proper residency status. “It’s a film, but one that intervened in the lives of the collaborators. The objective is not simply to attract short-term attention with an action,” he says.

But the biggest attraction remains Rau himself: 45 years old, born in Bern, studied sociology in Paris and who, while still very young, got into debt for a film project about revolutionaries in Chiapas in southern Mexico.

In Berlin he “accidently” got involved with a group of drama students and soon began directing. As for which medium and artform he decides to use at a particular moment: “That’s not so important, that’s also what I say again and again to students at art colleges.”

In his art, Rau is looking for friction with reality. If these contrasts are not stark enough, he intensifies them. The film has a Mozart soundtrack, which has a kitschy yet obscene effect in that the tone of European classical music collides, full force, with the harsh realities in the images. Perhaps he dreams of revolution, but at least of an impact beyond art.

A drive to enlighten

Rau talks to everyone – all the time. Talking is his supreme skill. He talks to field labourers, as in the current film. And he spoke to people from the ethnic group of perpetrators in the Rwandan genocide, as well as families of the victims, and enacted both, partly in reverse roles, on stage in Hate Radio. This work, from 2011, immediately catapulted him into the circle of top international theatre directors.

Because Rau himself talks so enthusiastically and eloquently, he has made use of the court format on several occasions. In the Zürcher Prozessen (Zurich Trials) at the Theater Neumarkt, he addressed the case of the increasingly right-wing Swiss newspaper Die Weltwoche. The Moskauer Prozesse (Moscow Trials) at the Sacharov Centre explored what the censorship of two exhibitions (and the trial concerning Pussy Riot’s “punk prayer”External link) was really about.

When Rau became famous, critics spoke of a renaissance of documentary forms in theatre, of re-enactments. In Die letzten Tage der Ceausescus (The Last Days of the Ceausescus) he re-enacts the firing-squad execution of the Romanian dictator; Hate Radio replays extracts from rabble-rousing radio programmes that incited the genocide in Rwanda.

I ask Rau if what he’s doing is still documentary theatre. “The documentary theatre of the 1960s in Germany was a public counter-discourse, because the Nazi past was barely mentioned in the mainstream media. That’s no longer something we have to do in theatre, and in that sense the function of pure documentary work has become obsolete in the liberal West.”

But does his Tell production not still have a documentary character, especially when he wants to illustrate so many current topics with authentic participants? He thinks for a moment. “I cite Schiller like a document that I pull off the shelf. This drama has a documentary character.”

The heart of Rau’s art is stimulated by a drive to enlighten. He wants to expose things, to observe them instead of simply narrating – in order to show that things are changeable.

Will he soon stage the first courtroom play in the history of German drama, The Broken Jug by Heinrich von Kleist (1808), which is still part of the Schauspielhaus’s repertoire? It tells the story of a corrupt village judge who is convicted in a trial that he himself presides over. Who could play the character? There’s no time to ask the question. I hear Rau striding back over the stage and shouting out “How is it, guys?” in broad Swiss English. Beep, beep, beep.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.