There’s oil in Lebanon’s northern hills

The Middle East may be famous for its black gold but on its western boundary not far from the Mediterranean Sea, the oil is flavourful and goes well with crispy bread.

Just beyond the Chuoar Valley waves of stone and scrub meander all the way to the horizon and the afternoon sun glistens through the olive groves of Youssef Fares and his family.

Lebanon, a small strip of land between the Mediterranean Sea and Syria, was once known as the Switzerland of the Middle East. Since it signed a free trade agreement with Lebanon several years ago, Switzerland is now helping farmers like Fares put the organic label on their bottles.

In the northern hills, business is growing for Fares but a good portion of his crop is missing a few things: mainly pesticides, genetically-modified seeds and a proximity to urban areas. Fares is one of the country’s few producers of organic olive oil.

A fifth-generation grower, Fares took over the family’s hectares five years ago, half a decade after a small group of Lebanese producers decided to go organic.

“The first year wasn’t in organic,” he told swissinfo.ch. “I started with that early 2005, so in 2008, we had our first harvest of organic certified. Now we’re expanding the farm.” Fares plans to expand from five hectares of organic to 20.

Surveying his fields is LibanCert, a company that ensures organic producers in Lebanon meet European and North American standards.

Free trade, premium oil

“Our aim is to sign free trade agreements with partner countries but at the same time with countries which still need support in particular areas; we offer them support so that they can better make use of the opportunities led out by free trade agreements,” said Hans-Peter Egler the head of trade promotion in the economic cooperation division at the State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (Seco).

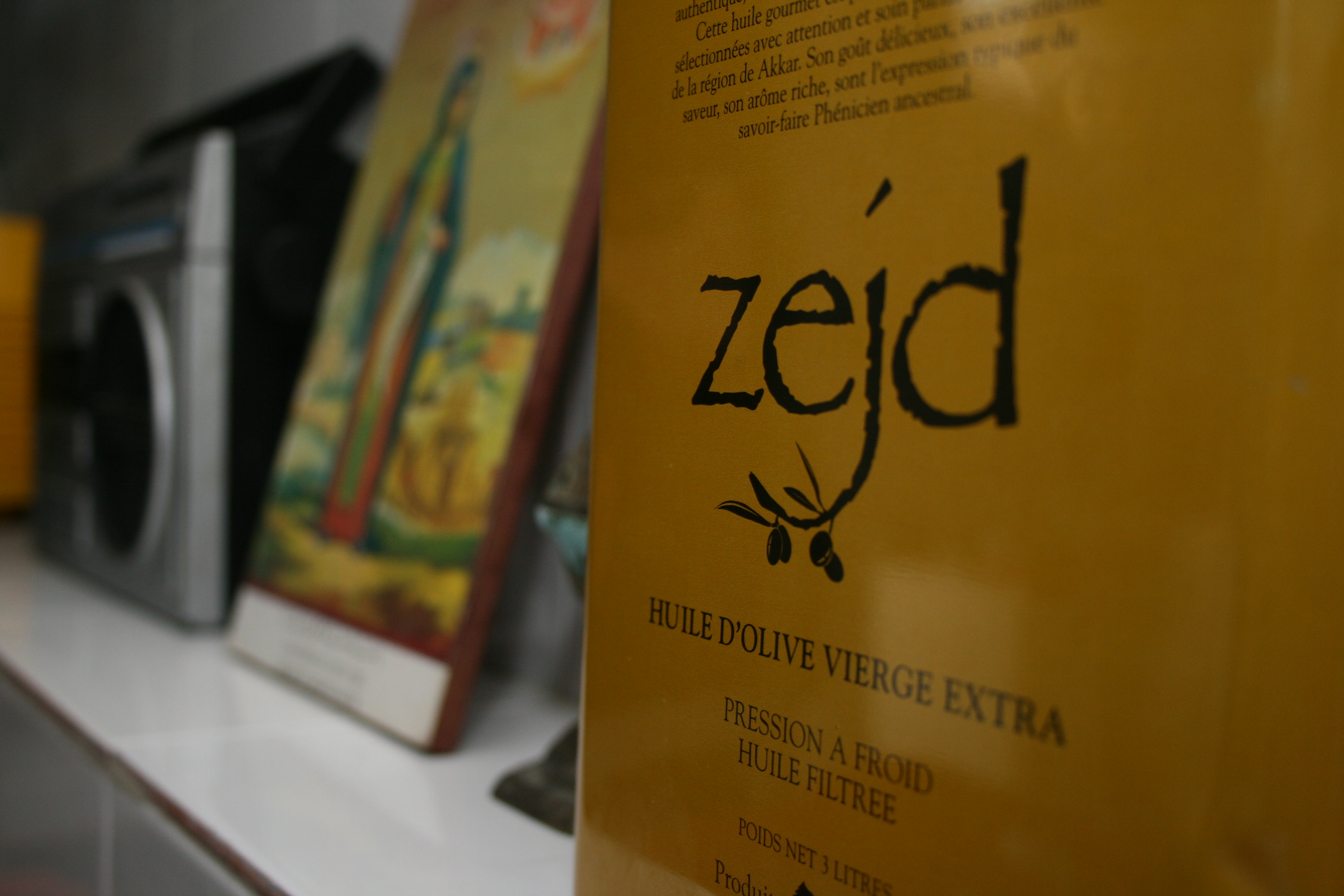

The oil that Fares produces and markets under the brand Zejd can carry a premium price abroad but is largely an unknown quantity at home. He nevertheless makes most of his sales in Lebanon.

“Basically, your price is going be 25 to 30 per cent higher, which is the average. Depending on the market and what you’re doing, it can vary, but this is the bigger picture,” he said on a tour of his groves.

“In a good year or a bad year, I have clients. And when you have clients you have to bring the olives. The issue is when you have a good crop, your cost is very low. When you have a bad crop, It’s harder to get the olives but it’s feasible,” Fares said.

When he first went organic, he was visited by inspectors from Bio Suisse, a standards organisation. Fares says he has tried to sell to Switzerland but with no luck. In the meantime, his company is introducing flavoured oils.

On the day swissinfo.ch visits, he navigates his small vehicle out of Beirut on the free-for-all that is the Lebanese motorway. He’s on the way to pick up 30 litres of pomegranate molasses to add to a batch. That too has to be organic.

Olives are cleaned and pressed beneath the family home. The whole process happens in less than a day, and the final product ends up in small bottles stored on the floor in crates, or steel tanks in a room next to the production equipment.

The oil flows with a perfect golden viscosity and tastes more authentic and completely different from anything extra virgin one would find in a major supermarket. It has won national awards in Lebanon.

Come together

But one of the problems for low-yield producers has been organising themselves, something that makes exporting a lot easier. There are still relatively few organic farmers, which makes the job more difficult.

“It was quite difficult to bring these people together and really stimulate them to get a clear vision of what they would like to do,” said Egler of his last trip to Lebanon.

Fares had a turnover of around $350,000 (SFr376,000) in 2009. He is hoping for $500,000 this year.

“The market is expanding,” said Therese Sfeir, an inspector for LibanCert.

“The problem is the producers converting to organic have a lack of technical know-how, a lack of assistance from government in the event of shortfalls in yields. There are several people interested that come to us but in the end, they take steps back if they go organic.”

LibanCert is a small, for-profit outfit. Like all certification bodies supported by Switzerland, it is driven by the private sector. In 2004 organic farmers in Lebanon saw a need for some kind of certification agency. Their three-employee group is now recognised by the International Organic Accreditation Service.

Seco’s partnership with LibanCert is carried out by the Research Institute of Organic Agriculture (FiBL), a leading centre of expertise both at home and abroad.

LibanCert has received SFr1.45 million annually; the funds are set to run out at the end of this year. Egler hopes it will be enough but does not rule out extending the project.

“Our goal is to help them be sustainable,” he said.

Justin Häne in Baino, Lebanon, swissinfo.ch

Olive oil has been produced for thousands of years, across the Mediterranean, North Africa and Persia.

The International Olive Council says that 2.77 million tons were produced in 2006-07.

More than 93% of worldwide production comes from four countries: Italy, Portugal, Spain and Greece.

Zejd oil is cold pressed and extra virgin.

Olives go through a grinder, stones and all, and are transformed into a paste.

The paste is then mixed with water before being pressed and put in a centrifuge, where the oil separates from the rest of the mixture. It’s then filtered and bottled.

But olive oil is also counterfeited on a large scale.

An August 2007 article in The New Yorker reported that fake oil had found its way into bottles distributed by big producers including Nestlé, Unilever, Bertolli, and Oleifici Fasanesi.

Sunflower and hazelnut oils are coloured and flavoured using a range of techniques ranging from very simple and easy-to-detect to very complex.

Fares says it would be quite easy to falsely label oil, as it often passes through many hands – from producers. dealers and distributors to stores shelves.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.