The deadly dilemmas facing aid agencies

Many aid workers have been killed, kidnapped and seriously wounded over the past two years. Agencies must tread an extremely fine line as they balance the dangers of doing their work against remaining effective.

Whether in Syria, Gaza, South Sudan, Ukraine or dozens of other dangerous regions, aid workers are paying an increasingly heavy price for doing their jobs. 2013 set a new record for violence against aid groups, with attacks on 460 aid workers, including 155 killed.

The figures look similar for 2014, which saw some particularly horrific incidents including the death of US aid worker Peter Kassig, who was taken hostage and then beheaded in Syria by militants belonging to the Islamic State.

“We are extremely concerned by safety issues,” declared Peter Staudacher from Caritas Switzerland, a non-governmental organisation active in several conflict areas.

Implementing projects and ensuring the safety of humanitarian workers on dangerous missions require special budgets and planning, he added.

Swiss NGO Terre des Hommes, which supports Syrian and Iraqi refugees in Lebanon, Jordan and Kurdistan in northern Iraq, faces similar concerns.

“We take various measures to avoid any kind of damage. This strategy doesn’t necessarily mean we can eliminate all the dangers, but it allows us to evaluate the situation on the ground for each field mission and to draw up a security plan to protect our workers,” said spokeswoman Zélie Schaller.

The safety of delegates is also a constant worry for the Geneva-based International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), which works in more than 80 conflict-ridden states.

“There are numerous security-related problems in Syria, Iraq and Libya which affect many of our people,” declared ICRC spokesman Dibeh Fakhr.

Difficult equation

Protecting staff while ensuring the effectiveness of field work is an extremely delicate, complex exercise.

“You shouldn’t be aiming to realise the objective you set in the field, come what may. What matters is to constantly evaluate the situation, enabling you to decide what is essential and what is non-essential,” said Staudacher.

This is a tricky balancing act to maintain, admitted Fakhr.

“Talking to all the various parties to a conflict sometimes requires a huge amount of time and difficult negotiations. We often have to make do with minimum security guarantees if we want to save the people who need us,” he said.

“Today there are many regions where we don’t have access, as we don’t have any authorisation. But what’s more problematic is that we are not free to act ourselves.”

Remove distinctive signs?

Adding barbed wire to the walls of residences or limiting workers’ movements may provide some security reassurances. But such initiatives just tend to widen the gap between agencies and beneficiaries.

In general, dissuasive strategies are only acceptable if they “save lives or bring aid that prevents disasters”, said Staudacher.

As for employing armed guards to protect workers, this just encourages local residents to see aid organisations as “being in the same boat” as any foreign armies present, he added.

Forced to be discreet, agencies sometimes have to drop their distinctive signs, logos or vehicles. But this can cause ambiguities surrounding an organisation’s identity and lead to mistrust among local workers.

Fakhr said there was no “magic formula” that could be applied in all difficult conflicts.

“They vary from country to country. Working in Iraq is not like working in Libya or Yemen. Each requires its own strategy,” he said.

Work with the locals

For Terre des Hommes, the most important thing is to remain open.

“Most of our staff are from countries where we work. This allows us to better identify local needs, which enable us to then draw up the right projects,” said Schaller.

Staudacher agreed, but added it was critical that locals did not end up “entangled in our own problems” and “exposed to dangers”.

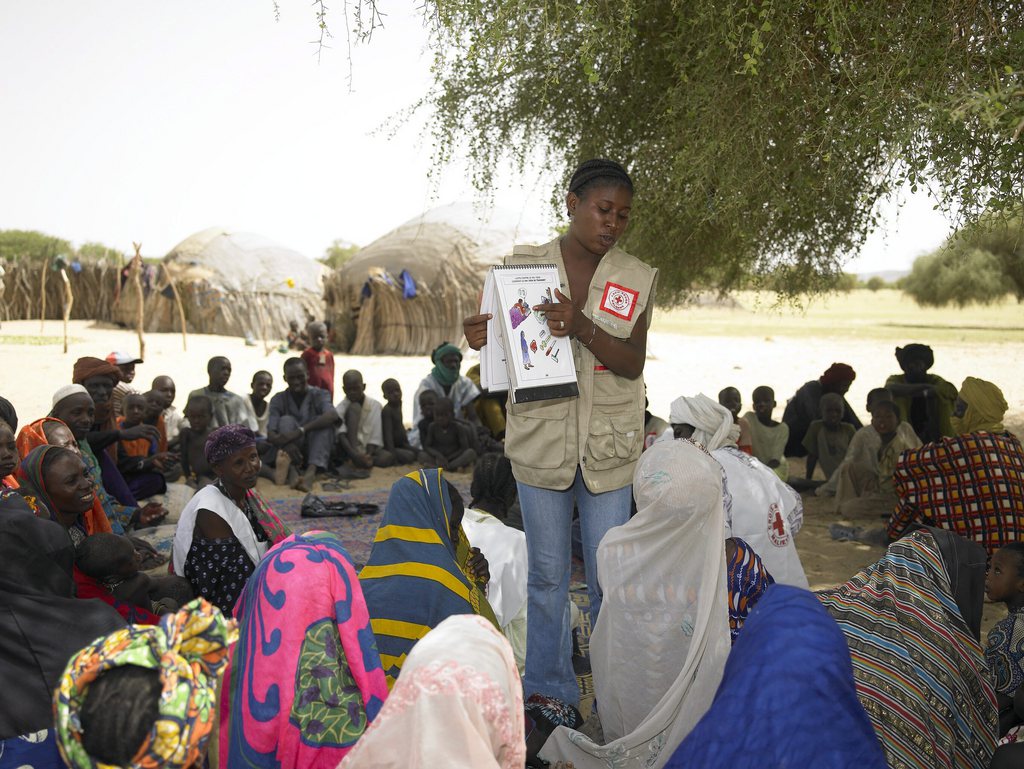

For its part, the ICRC tries to adapt to the customs and working methods of the country it is working in, said Fakhr. This is done in collaboration with its local partners on the ground – the national Red Cross or Red Crescent societies – which help implement projects or carry out negotiations with parties to the conflict.

Security can also be improved via information campaigns, listening and talking to the local residents and organisations, he added.

UN deaths

The United Nations Staff Union says at least 61 people working for the UN were killed in 2014 – up from 58 in 2013 and 37 in 2012. Last year’s victims included 33 peacekeepers, 16 civilians, nine contractors and three consultants. Mali was the deadliest place for UN personnel, with 28 peacekeepers killed in the volatile north between June and October. Gaza was the deadliest place for civilian staff with 11 killed during last summer’s war with Israel. Scores of UN staff and associated personnel were also detained, taken hostage and kidnapped during 2014.

Staff Union President Ian Richards has urged the General Assembly to do more to protect staff who face increased dangers.

(Translated from French by Simon Bradley)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.