Ukrainian jobseekers in Switzerland face uphill struggle

Many high-skilled Ukrainian refugees are looking for work in Switzerland. Matching them to jobs hasn’t been easy though. Their best prospects, say experts, require creativity and patience.

When 41-year-old health consultant Olga Faryma arrived safely in Poland after several weeks of travel with her daughters from Kyiv, finding a job was a priority. “A job is a basic necessity when you move all the time and you are alone with your kids,” she told SWI swissinfo.ch.

More

Why Switzerland needs workers from abroad

She looked for jobs all over Europe and then an acquaintance sent her a link to the Bern University of Applied Sciences, which was offering support for Ukrainian researchers.

Olga wasn’t a researcher but had created an NGO called BeHealthy to help children in Ukraine learn about good nutrition. Olga looked at the university website and found a professor that was doing research on a similar topic, and she reached out by email. Within hours, she received a response. A week later, Olga was on her way to Switzerland with a job offer to build a programme to address the health needs of refugee children.

Olga is a rare job success story for Ukrainian refugees in Switzerland.

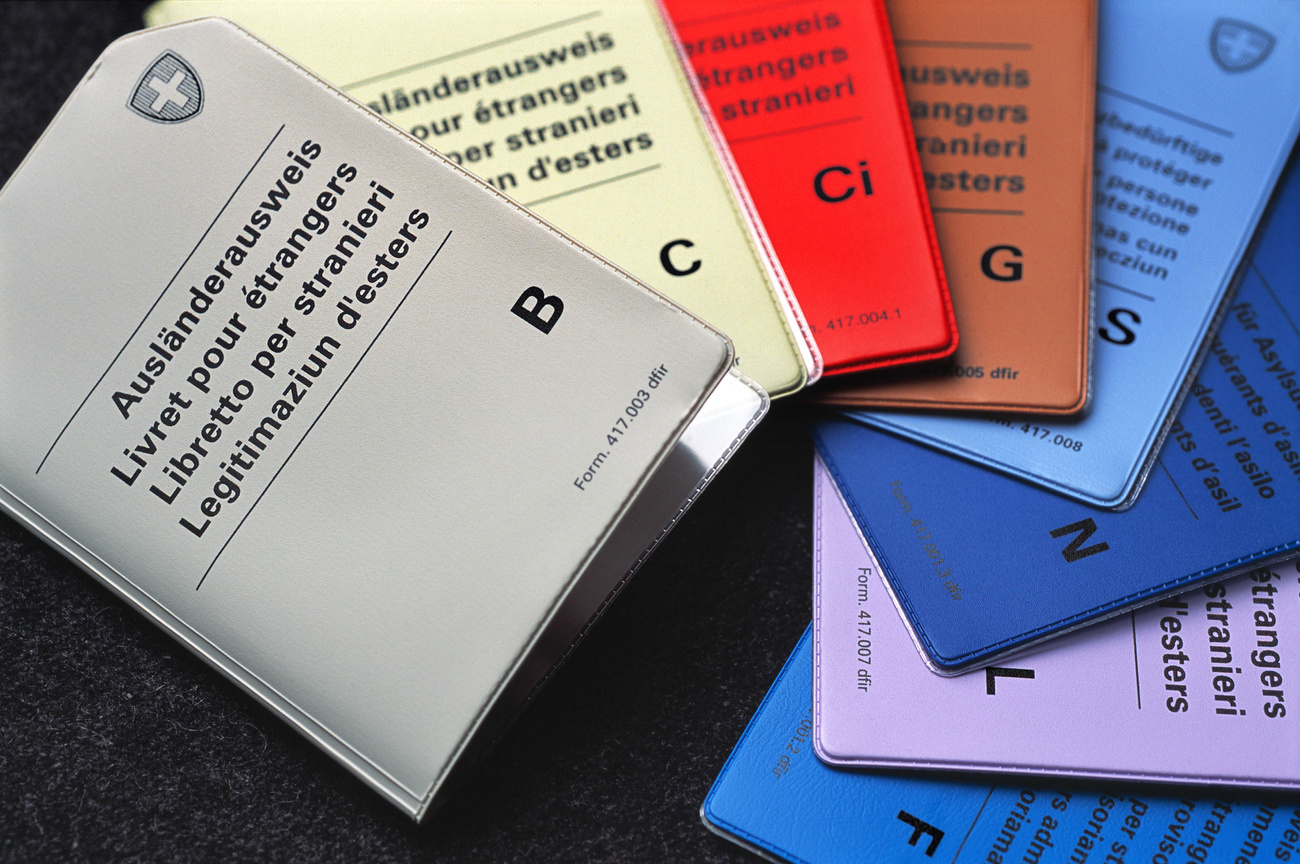

Three months after the Ukraine war started, Swiss authorities reported on June 16 that at least 57,000 refugees from Ukraine have applied for S Status. This status allows them to work, which contrasts with asylum seekers who receive an N permit and are required to wait at least three months before getting a job.

Since finishing her MBA in London, Hanna has been running her own event marketing company that works with clients throughout Europe. Her business was really starting to take off just as the war started.

Two weeks later, she was on her way to Switzerland. Her son, who is 14 years old, received an invitation to play water polo on a Swiss team so they both came and stayed at first in a sports complex in western Switzerland. They are now living in an apartment in Geneva.

Two months after they arrived, they received Status S and Hanna started to look for jobs. She adjusted her CV for the local market and used her Linkedin network. She has sent more than ten applications and only received, what seemed like automatic replies, informing her that she didn’t fit the criteria. One job said it was looking for 12 Ukrainians. She sent her CV immediately and never received any feedback.

“We are hard-working and learn quickly. Any employer who would give us a chance, they would see that we are good employees,” said Hanna. She has run many European projects but it was under the banner of her own company, not for a global company, which she feels is a hindrance when recruiters are scanning CVs.

Hanna said she understands there is high demand for these jobs given people all over Europe can work in this country. “In the middle of all this uncertainty, a job would give me some stability in my life.”

She has tried to attend local events and use Facebook networks. She is refreshing the French she learned many years ago. “It is important for me to be a part of society, to be helpful and contribute something. I’m at the age that I can do a lot of things. I’m not so young but not so old.”

However, only 1,500 of these have found work according to official data. This is 500 more though than two weeks prior. The Swiss Secretariat for Migration estimates this is about 3% of the working age population that have come to Switzerland because of the war.

“Considering that it’s only been three months since the start of the war, that’s encouraging,” said Justice Minister Karin Keller-Sutter in a press conference on June 1.

More

Switzerland steps up drive to integrate Ukrainian refugees in workforce

Many Ukrainians in the country, however, have been discouraged by the time it takes to secure a job in Switzerland. Despite the demand for high skilled workers, employers are not hiring Ukrainians at the speed, many, including Ukrainians themselves, expected when they arrived.

A different war for talent

One reason is that Switzerland is a highly competitive market, says Lidiya Nadych-Petrenko, a talent coach who was born in Ukraine and spent about 15 years working in human resources at a multinational company in Switzerland.

“Whenever there is a job in Switzerland, a lot of people apply who are highly qualified with lots of languages and great experience working across different European markets. Even high-skilled refugees from Ukraine likely come with less languages than other candidates,” said Nadych-Petrenko, who offers pro-bono advice to Ukrainian job seekers.

A surveyExternal link of about 2,000 Ukrainians in Switzerland by online portal Jobcloud in April found that 75% had a university degree, and about 63% mastered English. However, only about 10% had a good grasp of German and even less in French and Italian.

Inna has always been her own boss. After getting her PhD in economics, she started an ecommerce business with her husband. It was a popular website in Ukraine for buying luxury goods.

She and her husband were just putting the windows on a new house they bought in the outskirts of Kyiv when the war started. “I didn’t prepare for this war. I left my life. We spent all our savings to build a house,” says Inna.

“I thought it wouldn’t be difficult to find a job in Switzerland because I’m skilled and experienced,” said Inna. “Ukraine is not a wealthy country like Switzerland so out of necessity we had to move very quickly with technology. I thought my knowledge of technology would be an asset when looking for a job.” Inna doesn’t know German but thought her English would be enough.

She made a Linkedin profile and started sending her CV around to job applications. After three weeks, she only received one invitation to interview. Some people told her she was overqualified and that employers might be concerned that she’d resign quickly. “People told me I should start my own business here. But I don’t know the language or the market,” says Inna.

Inna received status S, which allows for self-employment but in order to start her own business she has to show the authorities that she has enough financial resources to support herself. People with status S can’t get any credit so she is looking at what financial resources are available in Ukraine. Another challenge for Inna is finding a preschool for her 4-year-old son.

The biggest source of inspiration, she says, is the support from women in Switzerland including one woman, who not knowing her, gave her an apartment and suggested she connect with the Women Rock Switzerland Facebook page where professional women in Switzerland offer support. Women in the network have been reaching out to friends to see how they can help her out. “They make me feel that I can do something; that I have enough strength, and that everything is possible.”

Inna’s business is nearly bankrupt. “No one needs Italian shoes during a war, she says. “I lost the life I had before the war. I had dreams to sell our business. It is an endless process of falling. For me, having a job is about being back on solid footing and defending my family.”

One factor that should ease some concerns is that Ukrainians aren’t competing for a limited number of work permits – something that has made it difficult for companies to hire people from third countries outside the European Free Trade Area. The Swiss Secretariat for Migration confirmed to SWI that Ukrainian refugees with S Status, as with other provisionally admitted persons in need of protection, do not count towards the quota for foreign workers from third countries.

But even then, companies often have their pick of good candidates. Switzerland’s largest telecom provider Swisscom told SWI via email that they haven’t hired any Ukrainians because they haven’t found a candidate whose profile fit the job requirements yet.

Certain professions are also harder than others. Most of the work permits that have been granted to Ukrainians thus far are in the hospitality sector followed by consulting, IT and agriculture. These fields have fewer regulated professions and less demands for specific qualifications or training.

While there is mutual recognition with the European Union for many professions, this isn’t the case for Ukrainians.

“For regulated professionals such as lawyers and doctors anyone outside the EU can’t just work in the EU. That definitely creates hurdles for Ukrainians,” said Urs Haegi, an attorney at Vischer law firm which has been providing pro-bono legal services to Ukrainian refugees. The firm hired two trained lawyers from Ukraine but, due to Swiss requirements, they aren’t able to work as certified lawyers in the country.

Hiring conditions are easier for global companies, especially in consulting or professions that can be done remotely. Consulting firm KPMG’s global group set up a dedicated platform to help Ukrainian colleagues apply for jobs at its member firms around the world. The Swiss office has hired five colleagues from Ukraine in their local office in Switzerland. However, some such jobs are still have a Ukrainian salary that is difficult to sustain in Switzerland.

Uncertainty in uncertain times

The greatest challenges may be beyond what’s written on a CV though. Employers still have worries about hiring refugees, says Nadych-Petrenko. They wonder how long they will stay and whether they are emotionally ready to take a job. “What’s happening in Ukraine is still unfolding and it’s natural that they are thinking about their family back home. That brings some concerns to employers,” said Nadych-Petrenko.

This was confirmed by initial findings of a follow-up survey Jobcloud is conducting with employers. Christelle Perret-Huwiler, a public relations manager at Jobcloud, told SWI that respondents expressed concern that “individuals want to return home, that they are traumatised by the war or will need too much support from the company outside of work”.

There’s also still a lot of uncertainty about how S status works. Authorities have been trying to distribute refugees across different cantons but many of the jobs are in the bigger cities like Zurich and Geneva. One employer said it would be helpful to know if candidates are already in Switzerland or not when they apply.

Oksana spent more than 12 years working for pharmaceutical companies in Ukraine. Nine of these were with the Ukraine subsidiary of a Swiss company. Oksana was promoted several times, reaching her most recent role as head of the sales department.

Ten days before the war started, the company sent a letter telling employees that they should have an extra canister of petrol prepared in the event they needed to flee. However, a day before the war started, the employer told employees that they couldn’t leave the country and work remotely for tax reasons. It wouldn’t be fair to allow some people to work from outside the country, the company told Oksana, according to her own account of the exchange.

Then the war started. Oksana remembers that fateful Thursday. “I was so glad the company told me to get fuel. The lines for fuel were so long.” Oksana crossed into Moldova and then into Italy with her son. Switzerland wasn’t far and someone she contacted online offered to host her in the country.

She wrote corporate headquarters in Switzerland about job opportunities and they responded that they would look into her case. Three months later, Oksana is still working for the Ukrainian affiliate, which means she has a Ukrainian salary that is difficult sustain with Switzerland’s high cost of living. As she focused on the Ukrainian market, her job duties have changed. She has been invited to attend meetings at the Swiss office but most of her colleagues are abroad. Oksana suspects the company is cautious about offering her a local contract because it could set a precedent for other employees.

Time is running out on her Ukrainian contract though. The company committed to pay her salary until the end of August. There is no guarantee after this. She has applied for two jobs at the company headquarters and sent her CV to at least 15 other job opportunities in Switzerland. She’s had two interviews, but no job offers as of yet. She feels her employer is trying to buy time in hopes that the situation will improve in Ukraine but the lack of clear answers about her job prospects is exacerbating uncertainty for her future.

She received status S and is grateful for all the support she has received but without a job, she worries she can’t support her son. “I am used to relying on myself. Now I depend on things that I can’t control,” says Oksana.

*name changed to respect anonymity.

Although companies feel a sense of solidarity to support Ukrainians, anecdotally, they also have reservations about hiring based on nationality and are conscious that other refugees haven’t been granted the same opportunities.

Sometimes expectations also don’t match. As Tages-Anzeiger reported a couple weeks ago, many refugees want to work full-timeExternal link but many job offers are part-time. Switzerland has the second largest share of women in Europe working part-time after the Netherlands.

Finding the right path

Nadych-Petrenko reassures though that job prospects will improve over time and employers’ reservations shouldn’t deter Ukrainians from trying. But she says that, like Olga, they should tap nontraditional channels to secure work.

“If Ukrainians just send their CV they most likely won’t succeed. There are so many good candidates. What’s different for them, is their network. It is their power,” said Nadych-Petrenko. The people around them, including those offering to host refugees are “the entry door to the market”.

More

Ukraine refugees work in restaurant and IT sectors

Several Ukrainians contacted by SWI said they’ve been impressed by the way people are willing to make connections for them, especially in women’s networks. “This exists in Ukraine, but we often see each other as competitors,” said Inna who ran her own e-commerce business in Ukraine. “Here in Switzerland, people share their experience, thoughts, ideas. You may be competitors, but you are colleagues first here. That is a big difference.”

Nadych-Petrenko adds that it is important to be flexible and think about the long-term benefits of getting work or training experience in Switzerland. She’s advising dentists, for example, to spend time working as an assistant at a dental office to build up their skills that they can take back to their practice in Ukraine.

Iryna started her career as a trainee at a global food company four years ago. After being promoted to brand manager, she was planning to move from her home in Lviv to Kyiv where the company was about to open a new office building.

Then the war started, and her sister, who was in the process of applying to a German university, was told she could take an assessment exam in Berlin instead of Kyiv. The two women in their 20s and their mother, who also works for a different food multinational, left Ukraine three weeks after the war started. Through the mother’s work colleagues, they were able to find a place to stay, first in Berlin, and then in Switzerland.

Both Iryna and her mother have continued working for their companies, remotely from Switzerland. They still have their regular work responsibilities in addition to providing humanitarian support. They continue to receive their Ukrainian salary and can get by because they don’t have to pay any rent. “We are three adult women. We don’t need a lot. I can’t imagine how women with young children can live here,” Iryna told SWI.

The company offers some extra money for anyone moving from one city to another within Ukraine or abroad. Iryna has also spent time at the Swiss office of the company to make contacts. “It was always a dream to come to the headquarters,” says Iryna. Colleagues from Ukraine are expected to provide daily reports to the company on their whereabouts.

“My work continues wherever I am. I am lucky to work for a global company that has international connections,” she says.

Many Ukrainians also see an opportunity to start their own business. People contacted by SWI said that various Telegram chatsExternal link are helping entrepreneurs exchange ideas for how to offer their services in IT, beauty, design and cleaning.

Employers in Switzerland also need to be flexible, said Perret-Huwiler. JobCloud has created a hashtag #Jobs4Ukrainians on jobs.ch to enable companies to specify jobs that might be a good fit for Ukrainians. “Companies should specify if German language skills are needed or whether good knowledge of English may suffice so as not to discourage candidates from applying.”

The tech company Scandit announced it is fast-tracking suitable candidatesExternal link from Ukraine who are currently in Switzerland among other European countries. They are also offering financial and legal support including visa and housing assistance. The company has received 272 applications so far from people displaced due to the war – the vast majority of for engineering jobs.

When Olga was in Poland, she made a list of all the possible things she could do. “I’m not good at picking strawberries but I know how to take care of people,” said Olga. “When your life changes so quickly, you are open to many possibilities.”

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.