When Swiss universities led the way in gender equity

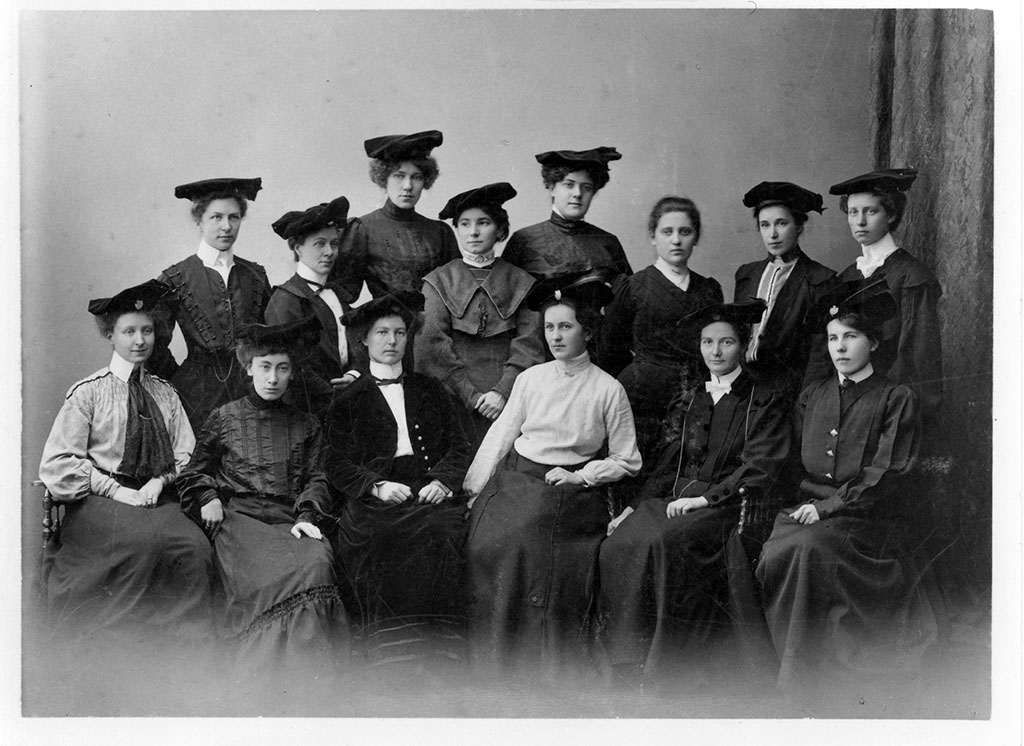

In the late 19th century, young women from all over the world came to Switzerland to study. They contributed to the development of medicine, law, philosophy, and other sciences in Switzerland and in their home country.

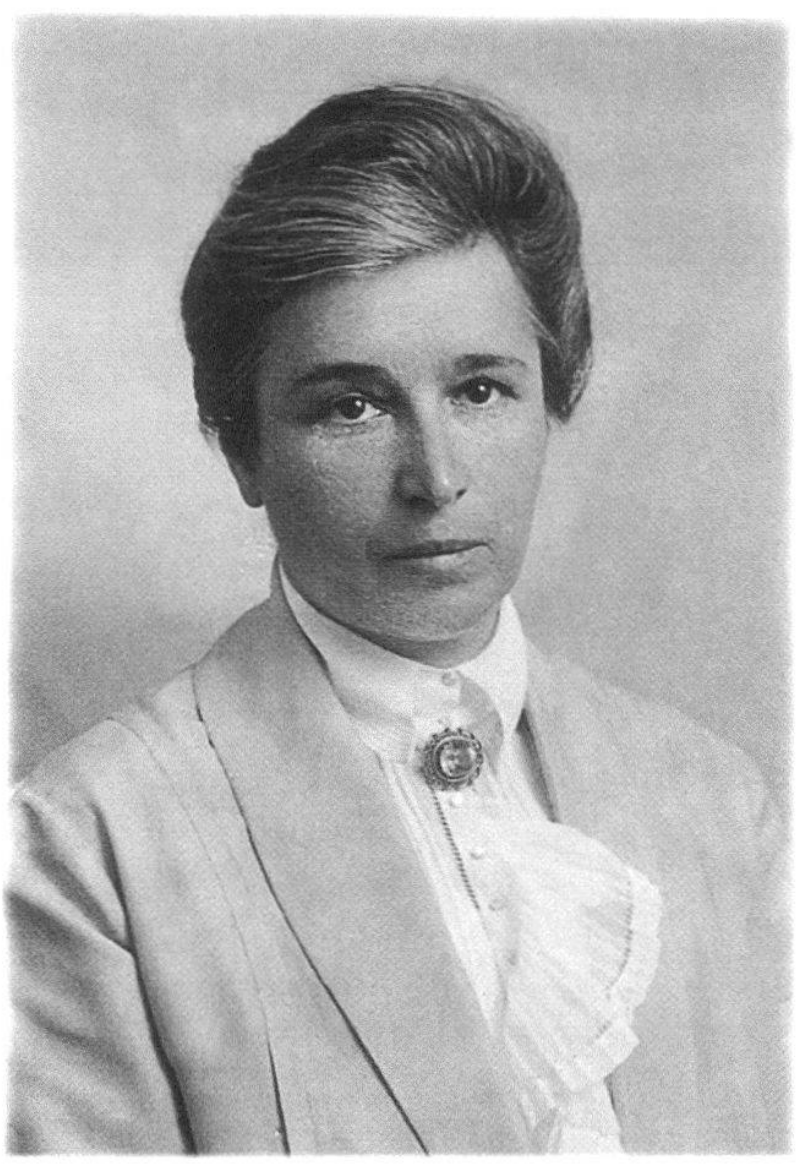

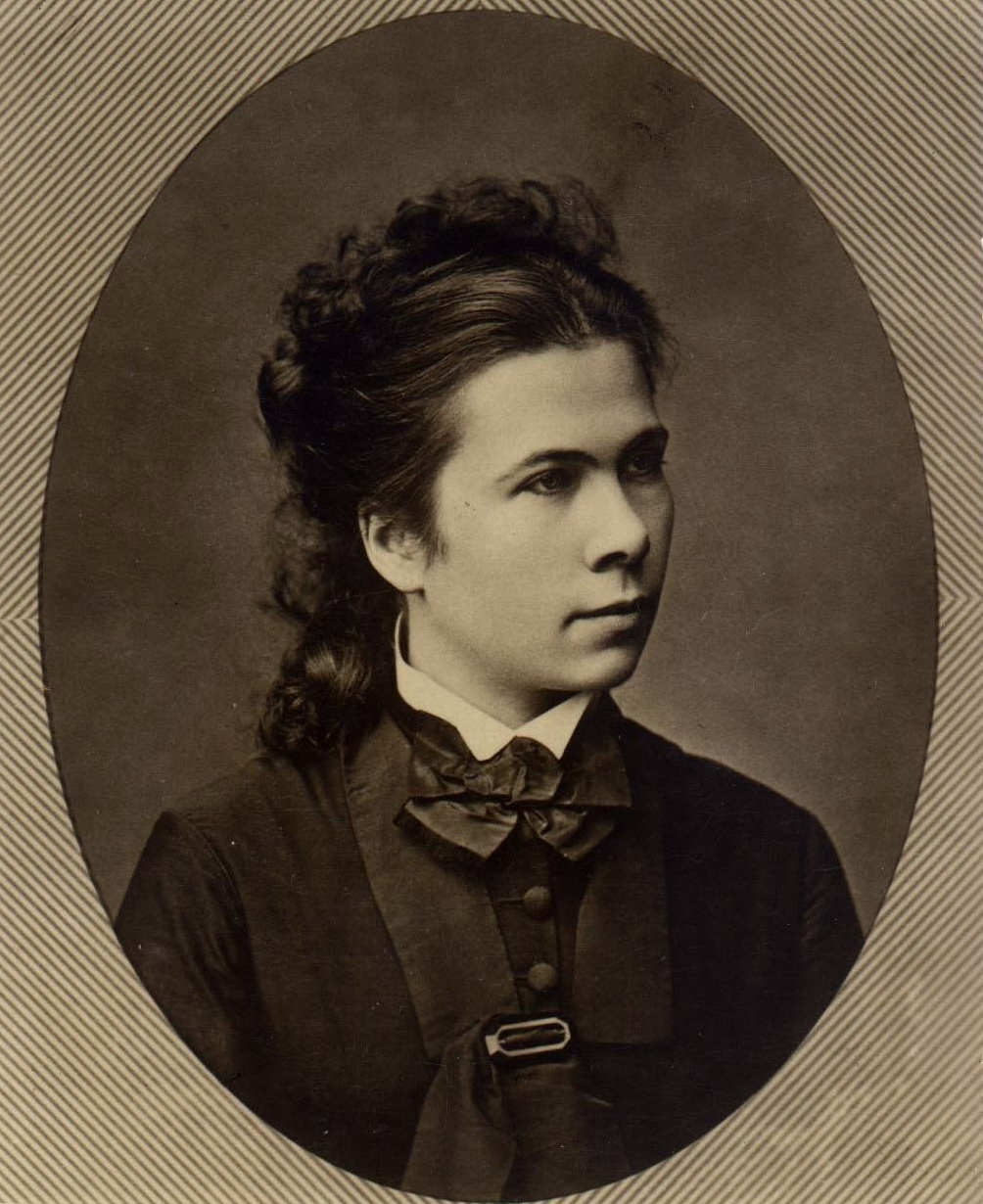

In the heart of Bern, close to the railroad tracks and the old university building, there is a short street called “Tumarkinweg”. It was named in 2000 after the Russian philosopher Anna TumarkinExternal link (1875-1951). A native of Dubrowna (now Belarus, formerly part of the Russian Empire), Anna came to Bern in 1892 at the age of 17 to study philosophy. She was following in the footsteps of her brother who was studying mathematics in the Swiss capital. She later earned her place in history as the first female professor in Europe who had the authority to supervise and test doctoral students.

The German word “Weg”, which means “path”, can be seen here not only as a geographical name, but also as symbol – that of an ambitious woman paving the way for others like her to access higher education. Tumarkin was among the first of many women, many of them from eastern Europe and Russia, to come to Switzerland to study at the turn of the last century.

She was joined by others, including Ida HoffExternal link (1880-1952), also a native of the former Russian Empire. Hoff studied medicine and became a doctor. She was one of the first people in Bern to purchase a car, which she drove herself, at a time when most were driven by a chauffeur.

When Hoff opened her own practice in 1911, there were 132 general practitioners in Bern, only four of them women. She and Tumarkin moved into the same house. The nature of their relationship has been described as “friendship and lifelong partnership”.

More

A woman ahead of her times

Other women pioneers in academia include the Swiss Emilie Kempin-Spyri, the first woman to obtain a Swiss law degree in 1887 who later founded a law school in New York, and Marie Heim-Vögtlin, another Swiss native from canton Aargau, who was one of the first women to study medicine in Switzerland. She later co-founded the first gynaecological hospital in the country.

Swiss exception

While most European countries were expanding their higher education campuses from the middle of the 19th century, what makes Switzerland stand out is that it allowed female students to sit side-by-side with male students.

Switzerland was already home to three universities in the German-speaking region. The oldest, the University of Basel, was founded in 1460; the University of Zurich was founded in 1833 and the University of Bern in 1834. The French-speaking part of the country also had a strong network with Geneva, Lausanne, Neuchatel and Fribourg all following suit and opening their own universities through the 19th century.

While the United Kingdom preferred to segregate men and women by creating same-sex colleges such as Lady Margaret Hall in Oxford and Girton College in Cambridge which were for women only, the University of Zurich welcomed female students as soon as 1868. Bern and Geneva did so in 1872. Swiss universities quickly attracted ambitious girls from wealthy families from other European countries. They came to study mathematics, medicine, sciences, psychology or law.

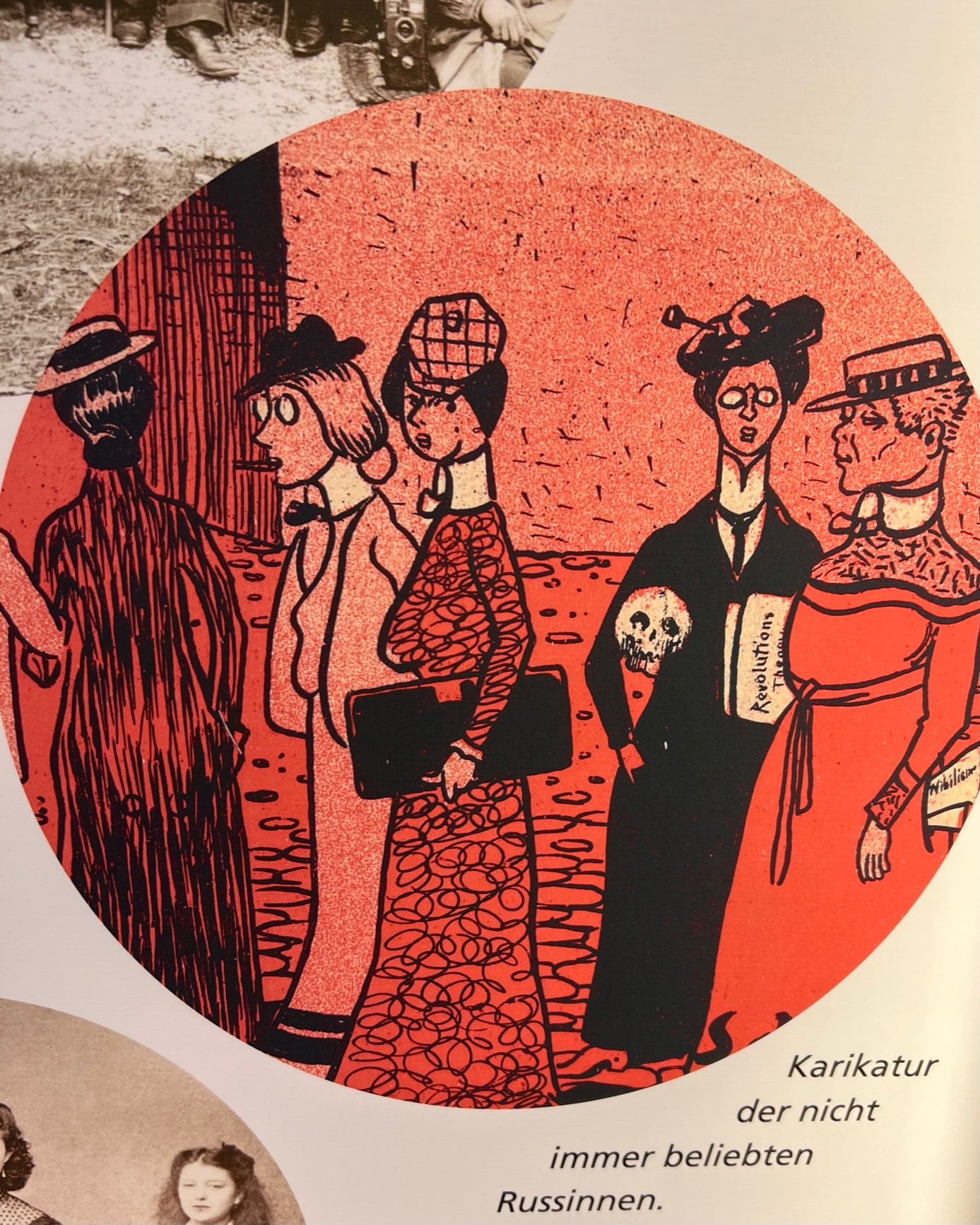

By 1900, almost all female students in Swiss universities were foreigners, and up to 80% came from the former Russian Empire where many intellectuals, including the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky, were pushing for equal access to education for women. “By allowing sincerely and completely higher education for women, with all the rights it gives, Russia would once again take a huge and unique step before the whole of Europe in the great cause of renewing humanity…,” he wrote in Vremya, a Russian literary and political magazine.

In 1906, a quarter of female university graduates globally came from Switzerland. They arrived in a country with a well-developed tertiary education network which provided rare learning opportunities for women at the time.

Their avant-garde choice was not an easy one. Women in Europe, in most cases, were not allowed to travel without permission of their father or husband. This led to many hasty or sham marriages. They also had to face social stigma at a time when women were still expected to marry and bear children.

What about Swiss women?

But while foreign women saw Switzerland as a gateway to higher education, Swiss universities remained surprisingly empty of Swiss women. “Despite the rather liberal admission policy of some universities, Swiss women wishing to enter higher education faced a difficult path,” wrote the researcher Manda Beck in an article published on the Swiss National Museum blog. The universities, while formally defending gender equality, only enrolled local young men. One of the admission requirements was to have attended the high school, which remained out of bounds for women. Girls’ schools in Switzerland did not offer the same programme. To be admitted to university and bypass the restrictions, they had to take expensive private courses and sit entrance exams.

“Marie Vögtlin became the first Swiss woman to attend medical school in 1868. This ambitious woman succeeded in passing the matriculation exam for which she had prepared herself. With her father’s consent, she obtained the right to enroll at the University of Zurich. Nevertheless, for a long time, the presence of Swiss women students in the university lecture halls remained low, their foreign counterparts being in the majority until 1914,” explained Beck.

Some universities remained closed to girls regardless. The University of Lausanne, for example, rejectedExternal link Swiss women from canton Vaud on the pretext that their education was incompatible with that of young men. However, it accepted women from other cantons.

The bumpy road to equality

By 1915, however, the number of foreign female students in Switzerland had equalled that of their Swiss female counterparts. Educated women, while remaining an exception, were less of a social taboo in Switzerland. The real shift in mindsets happened after World War One when the conflict forced women into the workplace. One by one, Swiss universities lifted their admission restrictions. Meanwhile, the war had stopped the flow of Russian female students to Switzerland.

In 1922, Geneva opened its first female gymnasiums which delivered high school certificates and enabled girls to apply to universities.

In 1924, the Association Suisse des Femmes Diplômées des Universités (ASFDUExternal link) (Swiss Association of Women Graduates) was founded in Bern to defend the rights of women graduates. This society was headed by Nelly Schreiber-FavreExternal link, a native of Geneva. She was the first woman to graduate from the Faculty of Law at the University of Geneva and later became the first barrister in the city. During her studies, her professors laughed at her, saying, she was a woman “playing at being a man”.

Competing against male lawyers, she mainly defended female clients and young people. She helped introduce several innovations to the judiciary system, such as juvenile delinquency courts; children were previously tried as adults. Schreiber-Favre initiated the creation of the École sociale pour les femmes (Social School for Women) in 1918, from which the Haute école de travail social (Geneva Institute of Social Work) was born.

Struggle to work

A university degree did not always mean work. Many of the foreign women who came to Switzerland stayed in the country to pursue their careers, such as Hoff or Tumarkin. By 1930, official statistics showed that most educated women had decided to work in the teaching or medical fields either as a doctor, pharmacist or dentist. None chose to work as engineers, for example. Law also remained largely closed to them.

More

Science in Switzerland: the women driving change

Some women opened their own offices, as did the doctor Hoff. Women with degrees in humanities and sciences taught in girls’ schools, such as Tumarkin. But they were the lucky ones. The reality for most women graduates was much bleaker. Professional opportunities for women remained limited.

Clara WinnickiExternal link was the first woman to study pharmacy in Bern in 1900 and the first to successfully pass the federal state examination for pharmacists. This entitled her to run her own pharmacy. Nonetheless, she struggled to find an internship and later an assistant position in a pharmacy. The two pharmacies she was finally able to open filed for bankruptcy.

Obstacles

After the financial crisis of 1929, despite universities further opening to women, the job market became even more difficult for them. Employers preferred taking on men and were more skeptical towards women’s skills. Unemployment was also high.

At that time, Switzerland implemented certain progressive social measures such as unemployment benefits and a national pension system. But the country also passed laws to exclude married women from the labour market, promoting the motto “one family – one income”. Families with two incomes were discouraged, especially if the woman of the household was employed as a teacher or a civil servant. These jobs were often seen as a “luxury”.

“Campaigns against dual income never target men who are gainfully employed…. or married women working in factories, in crafts and on farms. For if the salary of a female worker undoubtedly served to support the family, the money earned by a married teacher or civil servant symbolises luxury. These women, therefore, should leave their well-paid public jobs to men with families to support,” wrote Erika HebeisenExternal link, a historian and curator at the Swiss National Museum, in a blog entry.

PLACEHOLDERCanton Basel, for example, banned married women from becoming teachers in 1926.

These policies drove qualified women out of the workforce and had long-lasting effects on how women in Switzerland were perceived by society. By the World War Two, the first wave of progressive women gave way to female students who often started their studies but did not finish them. Those that did, chose not to work. They typically married and devoted themselves to their families. Discouraged by the controversies against women in the workforce, many scaled back their professional ambitions.

At the beginning of the 20th century, just under 10% of women in Switzerland graduated with a degree. But by 1935, women were making up 16% of the student body. This proportion remained stable until the 1960s, when mixed secondary education and women’s access to higher education became widespread. Nowadays there are even slightly more women than men studying: in the academic year 2021/2,External link they accounted for almost 52% of students at Swiss universities.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.