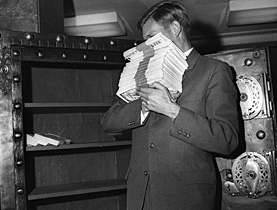

White collar crime “certain to rise”

Fraud in the work place, that already costs the Swiss economy around SFr8 billion ($9.4 billion) a year, is set to increase, according to experts.

The recent recession has enhanced the environment for white collar crime by slashing bonuses and share prices while increasing pressure on workers. Stretched companies are also struggling to devote enough resources to tackle the problem.

Because the average fraud takes 3.4 years to detect, professional services group KPMG believes that many crimes may already be running under the very noses of firms.

The KPMG corporate fraud survey looked at 348 cases it had investigated in 69 countries between January 2008 and December 2010.

While the company did not have statistics to prove corporate crime was on the rise, KPMG’s head of corporate client forensic services John Ederer pointed out that his department has tripled in size in the past few years to cope with the demand for investigations.

Missing signals

“There are a lot of small family owned businesses run by patrons who place a lot of trust and responsibilities in individuals,” he told swissinfo.ch. “This structure leaves them particularly exposed to fraud.”

The weak link of any organisation are the individuals – typically men aged between 36 and 55 who have been at the company for at least five years – who decide to rip off the firm to fund extravagant lifestyles or because they feel they are undervalued.

To make matters worse, many companies lack the resources to tackle fraud and even ignore red flags until it is too late, according to Ederer. One in seven cases of corporate fraud are detected by pure chance, such as a new employee taking over a fraudsters work position.

These flags include secretive behaviour, evidence of addiction or gambling, missing or late documentation and employees refusing to take long holidays.

“We fear there should be a lot more cases being investigated,” Ederer told swissinfo.ch.

Hush-hush

When fraud is detected, it is dealt with in-house 80 per cent of the time to avoid giving the business a bad name.

A KPMG report earlier this year found that the Swiss courts dealt with fraud cases that cost firms SFr365 million in 2010 – down from the SFr1.5 billion in 2009 when judges dealt with a massive tobacco smuggling case.

But KPMG believes this represents the “tip of the iceberg” – a fraction of the 20 per cent of cases outsourced to professional investigators.

“As long as companies get their money back and avoid negative publicity, in most cases everything is fine with the world,” Peter Liebfried, director of the institute of accounting, controlling and auditing at St Gallen University, told swissinfo.ch.

New trends

The KPMG survey also shed light on the changing patterns of white collar crime.

In Switzerland, there is a growing trend for fraudsters working within a company to collude with outside partners. Some 32 per cent of fraud involved an outside third party in 2008 compared with 61 per cent now.

There is also an increasing tendency for fraudsters to target family offices – an upcoming breed of wealth management advisory service dedicated to managing the assets of very rich families.

The fact that fewer women commit fraud in Europe compared with the United States and Asia points to the dearth of female senior managers in countries such as Switzerland, according to the report.

Companies expanding into Asia to exploit new growth opportunities and escape the perils of the strong franc are more likely to run into fraud. “This region has a very challenging fraud environment,” Ederer told swissinfo.ch “While fraud legislation is strict in Asia, small bribes are considered more acceptable than in Europe.”

One trend that remains the same is Switzerland’s aversion to whistle blowing compared with the US. While the Swiss parliament will discuss new legislation this year to improve protection of whistleblowers, the concept seems harder to swallow in Switzerland, according to Ederer.

“It is culturally far more difficult to promote whistleblowing in Switzerland than it is in the US,” he told swissinfo.ch.

KPMG has identified the profile of a professional person most likely to commit crimes in the work place.

The “average” white collar criminal is male, aged between 36 and 55, and will have been at his company for at least five years.

Senior managers that hold a finance related role (for example, accountants or financial officers) are the most likely perpetrators.

Finance positions accounted for 32% of fraud cases, followed by chief executives (26%), operations/sales employees (25%), procurement specialists (8%) and board members (7%).

The remaining culprits were in the back office or research and development areas – but represented a tiny fraction of perpetrators.

Offenders are often extrovert in character, in many cases domineering in the work place, evade questions, refuse to take long holidays and are apt to take risks.

The main motivation was funding an expensive lifestyle, disillusionment with the company or being under pressure to deliver on targets.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.