Can the ballot box help save Romansh?

Switzerland’s oldest language is threatened with extinction. Can public votes help save Romansh? And who should be allowed to decide?

At first glance, you might think that Switzerland’s system of direct democracy would be an ally for Romansh: when 91.6% of Swiss voted in favour of recognising it as the fourth national language in a nationwide vote back in 1938, there had hardly ever been such a clear verdict at the ballot box. Church bells rang across Romansh villages that day.

Another national referendum in 1996 saw Romansh recognised as a partially official government language by a 76% majority, allowing Romansh citizens to correspond with government authorities in their own language and requiring certain government texts to be published in the official written form of Rumantsch Grischun. Before that decision, Romansh speakers could only communicate with the authorities in French, German or Italian.

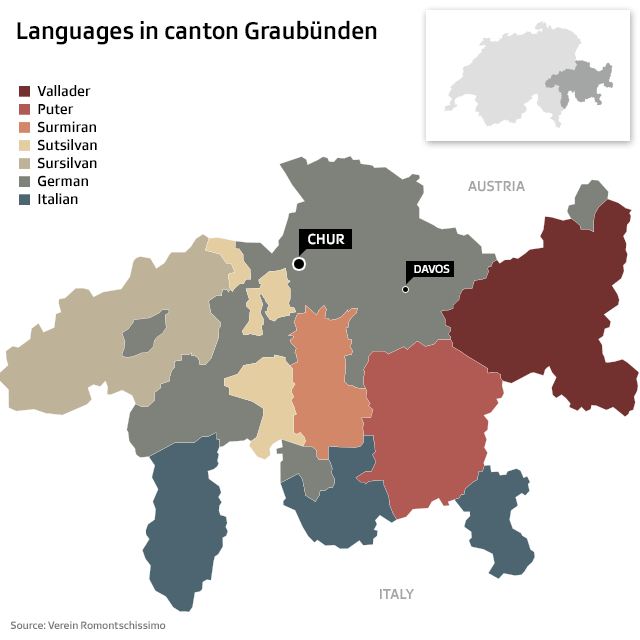

Romansh had already been an official language of the trilingual Canton of Graubünden since 1880, alongside German and Italian. Voters there are frequently invited to vote on matters relating to Romansh: in 2007, for example, they approved a law under which Romansh was deemed the only official language in municipalities with a 40% or greater Romansh population. But it’s a rather mathematically absurd rule since that means as many as 60% of those municipalities’ populations could actually be German-speaking. With this formula, the cantonal legislature aimed to stave off the gradual “Germanisation” of the area where Romansh is spoken.

More

Switzerland’s smallest national language struggles for survival

Centralisation is toxic for minority languages

The national and cantonal referendum results indicate that the Swiss view Romansh quite favourably. In fact, this can generally be said about places where no Romansh is spoken at all, with the exception of the German-speaking enclaves in Romansh areas. For instance, in the late 1990s, voters in the German-speaking municipalities of Vals and Samnaun in canton Graubünden refused to teach Romansh as a foreign language in their schools.

By comparison, local minority languages have been heavily suppressed in centralised countries without a direct democracy system such as France. Does that make direct democracy a lifeline for Romansh? Corsin Bisaz from the Aarau Centre for Democracy doesn’t go that far. But he believes that direct democracy could be used to clarify key issues such as the controversy surrounding the artificial Rumantsch Grischun language, meant to create a single version of the language for official correspondence and school teaching.

Only those affected should get a vote

Bisaz believes direct democracy could even serve as a disadvantage to Romansh, since the Romansh people are in the minority in canton Graubünden. “The German-speaking Swiss in the canton are more in favour of the artificial language of Rumantsch Grischun, while the Romansh themselves tend to want to preserve their own idioms,” he says. To Bisaz, this begs the question as to whether a cantonal popular decision is even a legitimate option for deciding the issue.

He especially remembers the 2001 vote on whether Rumantsch Grischun should replace the two idioms previously used on official voting documents. Most voters in the canton accepted it, but it was rejected by municipalities with a Romansh-speaking population of 30% or more.

Bisaz thinks it would be best if all the Romansh people in Switzerland would vote on the issue by means of an electronic ballot, for example. To him, one of the strengths of the Swiss system has always been letting those directly affected by an issue decide on it. But, having people’s language group rather than their place of residence dictate their right to vote on an issue would be a first in Switzerland.

“From a constitutional point of view, my proposal is utopian,” Bisaz admits.

The Rumantsch Grischun question

Conflicts over which Romansh idiom should be used in the public sphere or taught in schools have raged for many years, especially over the question of whether to introduce the artificial language “Rumantsch Grischun”.

The government and canton use Rumantsch Grischun in correspondence. Even the Romansh umbrella organisation Lia RimantschaExternal link supports the artificial language, standing behind the canton when it passed a resolution in 2003 to publish teaching material exclusively in Rumantsch Grischun in order to cut costs.

But the Romansh-speaking people are fairly unimpressed with Rumantsch Grischun and have retaliated with initiatives and legal proceedingsExternal link. The “Pro IdiomsExternal link” association was set up to lead a countermovement, while some schools are now teaching an idiom again.

Contact the author @SibillaBondolfi on Facebook or Twitter.

Translated from German

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.