Swiss back genetic testing of embryos (again)

Swiss voters have approved a modification to the law on medically assisted reproductionExternal link (RMA) legalising genetic tests on in vitro embryos, before they are implanted in a woman's uterus. Switzerland is the last country in Europe to approve the practice.

Sunday’s vote, in which 62.4% of people backed the change, is the second time in a year that the Swiss have been called to decide on the issue.

Last June voters approved the cabinet’s revision to the Swiss constitution, which created a legal framework within which preimplantation genetic testing of embryos could be practised, but without detailed guidelines.

Parliament then modified the RMA to provide such guidelines, but opponents argued that the language of the revised law was too broad, forcing a referendum.

Implementation wheels in motion

In a press conference Sunday afternoon, Interior Minister Alain Berset said that the Swiss population’s second majority vote in favour of preimplantation genetic tests meant that they should be implemented in the country in about a year, in four or five select clinics. But first, the cabinet would need to discuss the application of the revised RMA.

Parliamentarian Regine Sauter of the centre-right Radical Party and the committee in favour of the law, said in a statement on Sunday that the result “is nice proof of the confidence of citizens, and shows that the popular voice honours the work of parliament“.

For parliamentarian Anne Seydoux-Christe of the centrist Christian Democratic Party, the result eliminates an inconsistency in Swiss law. “Why allow prenatal diagnostics at [11 weeks] of pregnancy, but forbid embryonic analysis outside the uterus?” she said.

Mathias Reynard, a left-wing Social Democratic Party parliamentarian and co-chair of the cross-party committee opposing the law, said the result was “somewhat expected” given last year’s vote, adding that the next step was to ensure that the legislation does not go any further.

“We are not satisfied with the result, but happy with the debate,” said Christa Schönbächler of insieme.chExternal link, the association of parents of mentally disabled children. “We now need supporters keep their promise that the authorisation of preimplantation genetic diagnosis will not lead to discrimination against people with disabilities.”

Letter of the law

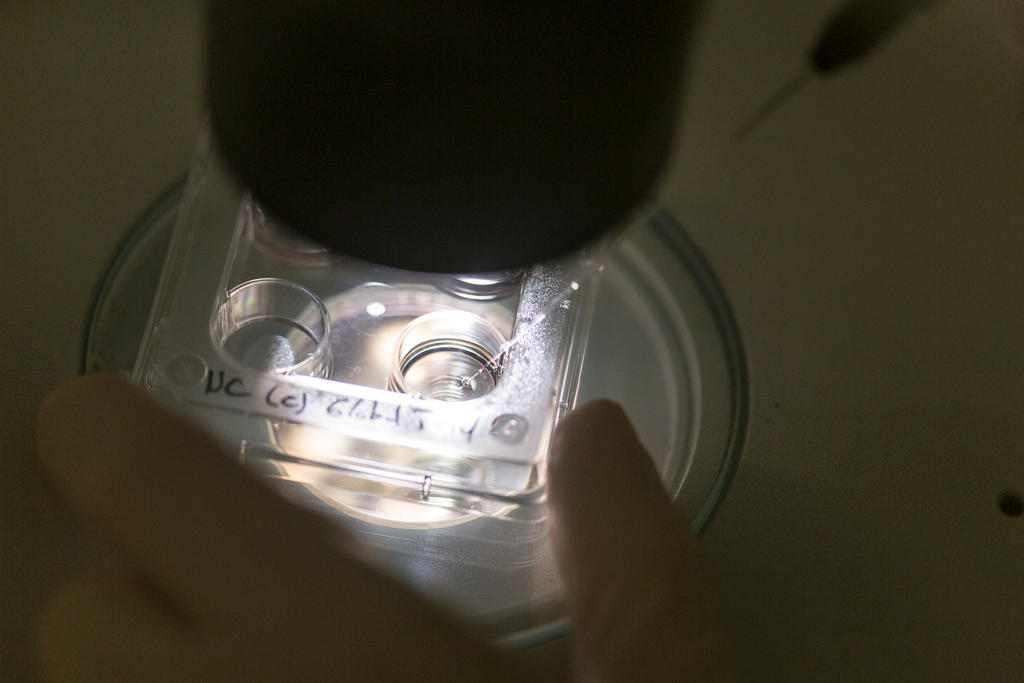

The revised RMA is designed to legalise testing of in vitro embryos of couples who are carriers of a “serious” genetically transmissible disease in a practice known as preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD). It also allows the embryos of infertile couples who conceive via IVF to be screened for chromosomal abnormalities – a primary cause of miscarriage – in a practice known as preimplantation genetic screening (PGS).

More

Preimplantation diagnosis explained

The revised RMA makes both PGD and PGS possible by allowing doctors to create up to 12 embryos during an IVF cycle, and to store some of them via freezing to allow time for testing. Previously, it has only been legal to produce three embryos at a time, and freezing has not been permitted.

Selecting embryos for a certain sex or eye colour will still be illegal, as will selecting embryos specifically to provide stem cells to treat an ill sibling.

Divisive moral issue

Proponents have argued that legalising PGD and PGS could help parents avoid transmitting genetic disorders to their offspring, help infertile couples using IVF to avoid miscarriages, and ensure that couples no longer need to travel outside of Switzerland for treatment. Tests cannot be covered by Swiss compulsory health insurance, so the cost burden lies only with the patients.

Opponents from across the political spectrum, led notably by the centrist Protestant Party and right-wing People’s Party, have argued that allowing PGS as well as PGD would create a slippery slope toward eugenics, and the production of “designer” or “GMO” babies.

Another concern has been that those with disabilities, as well as parents who choose not to test their embryos, could become stigmatised or discriminated against. Organisations for the disabled opposed revising the law on the grounds that PGD could deny those with hereditary diseases their right to life.

Basic income initiative:

23.1% yes 76.9.% no

Asylum reform:

66.8% yes 33.2% no

Pre-implantation genetic diagnosis:

62.4% yes 37.6% no

Public service companies:

32.4% yes 67.6.% no

Road traffic funding:

29.2% yes 70.8% no

Turnout: 46.4%

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.