Making sense of the post-Brexit debate on democracy

The decision by the British electorate to leave the European Union has created a worldwide discussion on the limits and potential of the referendum process. In the future, June 23 may be seen as a tipping point.

When a majority in the plebiscite-referendum voted to leave the EU, it created gigantic political and economic waves across the globe. With presidential offices in China and the United States commenting on the result, Brexit may have won the most attention of any referendum in history.

In the slipstream of post-Brexit-eruptions, another kind of debate has emerged. It is about modern direct democracy, and asks: Should the people be allowed to take such far-reaching decisions at the ballot box? If the answer to that question is yes, under which rules should such votes be possible? And what kind of modern direct democracy should the world adopt?

Brexit is only the third-ever UK-wide popular vote in British history, and it posed many questions about when and how indirect legislation by an elected parliament should be decided by a popular vote.

The voting, as an administrative matter, was conducted in an exemplary way by civil servants and polling station volunteers across the UK. But the vote came in a very difficult political and legal framework that has given people many reasons to offer legitimate and critical assessments of the process.

The UK does not have a constitution like other countries, where the principles and key procedures of referendums are defined, although it has used direct popular votes on issues, including three UK-wide, 11 nationwide and 61 local ones since the millennium.

Problem with plebiscites

It is left up to the elected prime and first ministers to decide when and how the people will have a say.

More

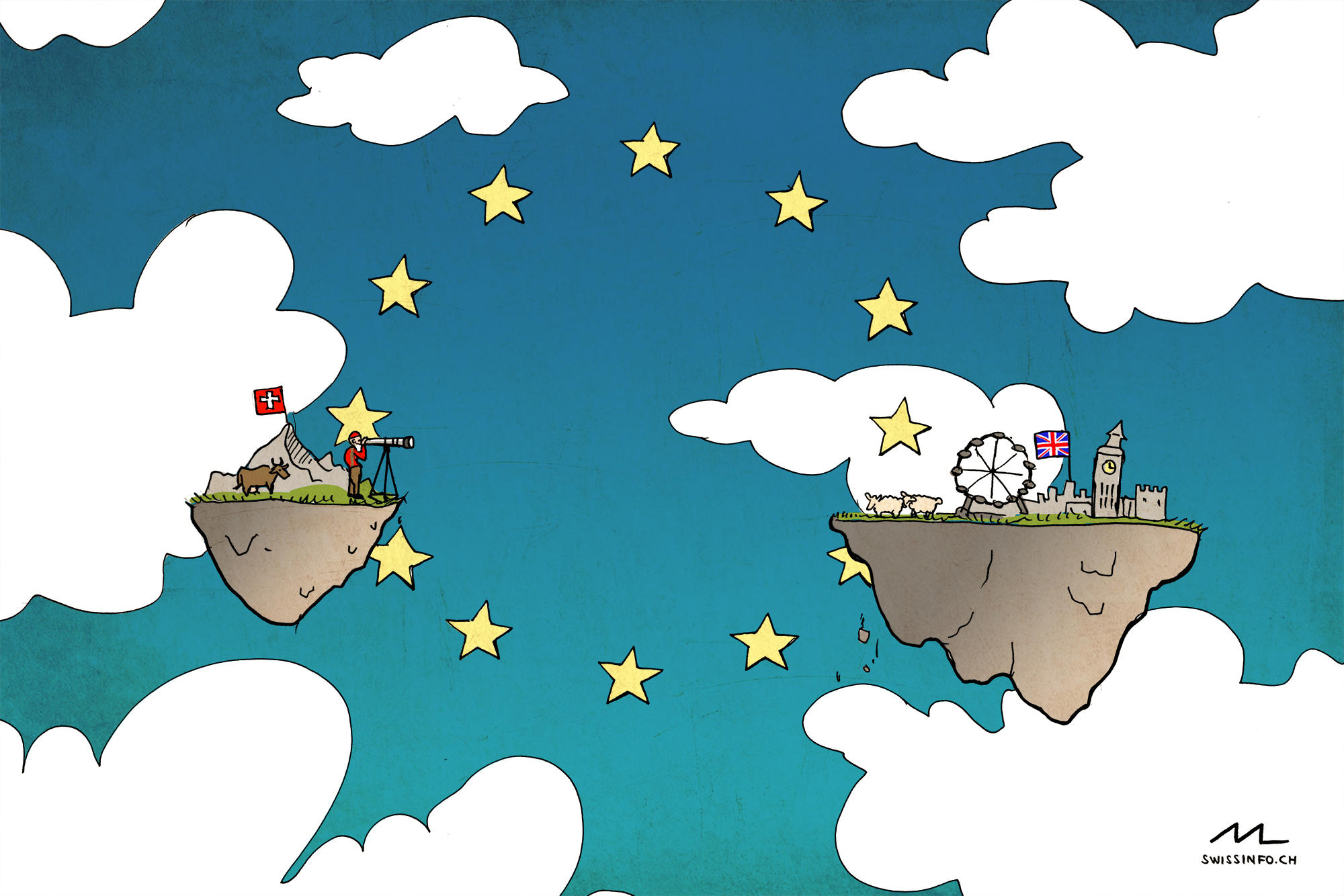

Swiss weigh up consequences of Brexit vote

This form of “direct democracy” is also popular in much less democratic countries than the UK but it has severe drawbacks, in that it offers politicians and powerful interests many ways to manipulate the vote.

These plebiscite-style “referendums” often produce a backlash against the initiator of the referendum (in Brexit’s case, Prime Minister David Cameron) and can offer a platform for demagogic and populistic movements.

The very fact of Brexit offers another lesson: that for real progress and pro-active efforts you need some real crisis and drama, thus engaging far more people in the political process and in the key questions of modern direct democracy.

Brexit was a superb example of all of these problems. No wonder some of the losers in the June 23 decision immediately started a petition to both reverse the vote as such and to propose a change in the rules, demanding a 60% supermajority approval rate combined with a 75% turnout quorum.

A few days after the referendum, this petition to Westminster had won the support of more than three million people.

Reaction elsewhere

Beyond Britain, an ugly debate continued over the referendum and its impact. Populist and xenophobic parties across the EU, including Dutch party leader Geert Wilders, French presidential hopeful Marine Le Pen and the Swedish post-fascists immediately jumped on the Brexit bandwagon to praise the “victory of democracy” in Britain and to demand similar votes in their own countries on leaving the EU.

The endorsements of the populist right has triggered its own backlash, with others questioning the very idea of popular votes on issues.

This referendum scepticism was led by the formerly pro-participation weekly, The EconomistExternal link, and echoed by pressured political leaders across the EU.

The Global TimesExternal link, the English-edition of the Chinese Communist party’s official newspaper, summarised: “By employing a referendum, the Cameron government opened a window of opportunity for direct democracy. Not a wise decision.” The forecast from Beijing: “The Western world will have to reflect on liberal democracy and social Darwinism.”

Reflecting on democracy at home

Luckily, the debate is not dominated by these predictable and opportunistic contributions by both populists, anti-populists and democracy critics. Across the globe, the Brexit attention has instead invited thinkers and citizen activists alike to look beyond the current controversy and to examine their own democracies.

Many voices are welcoming the very idea of involving citizens more directly into the decision-making process.

The Asian-Pacific magazine, The DiplomatExternal link, underlined that the “take-away from Brexit shouldn’t be a hardening of contempt for popular will and the one-person-one-vote principle that underwrites all forms of modern democracy, but to continue to expect politicians to be politicians”.

In the Tokyo-based newspaper, editors used Brexit as an opportunity to discuss the pros and cons of referendums in Japan.

Similarly, a Nigerian business magazine, Ventures AfricaExternal link, wondered if time for more direct democracy had come to Africa’s most populous country.

In Canada, political leaders from various parties have welcomed the debate on how referendums and direct democracy should be strengthened, in connection with a forthcoming popular vote on an electoral reform.

In addition to the back and forth in traditional media, individuals and groups worldwide have joined the conversation on the merits of more direct democracy on social media networks including TwitterExternal link and Facebook.

This conversation is complemented by new efforts across Europe and the world to discuss the future of transnational governance structures and their democratic legitimacy — as it relates not only to the EU and other continental unions but also to free trade agreements like the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

More

Switzerland’s special EU deal

Bruno Kaufmann is an expert on direct democracy and acts as editor-in- chief of the people2power platform, created an hosted by swissinfo.ch. He also works as correspondent for Northern Europe for Swiss public radio and is president of the Initiative and Referendum Institute Europe and co-chair of the Global Forum on Modern Direct Democracy.

This is a slightly adapted version of a text first published by the online global democracy platform people2power.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.