Deportation initiative back before voters

The Swiss People’s Party believes that parliament has watered down its initiative calling for the deportation of foreigners found guilty of a crime. In response, the party launched the so-called enforcement initiative which follows the law to the letter. Opponents, however, argue that the proposal encroaches on the separation of powers.

The Swiss will vote on the issue on February 28.

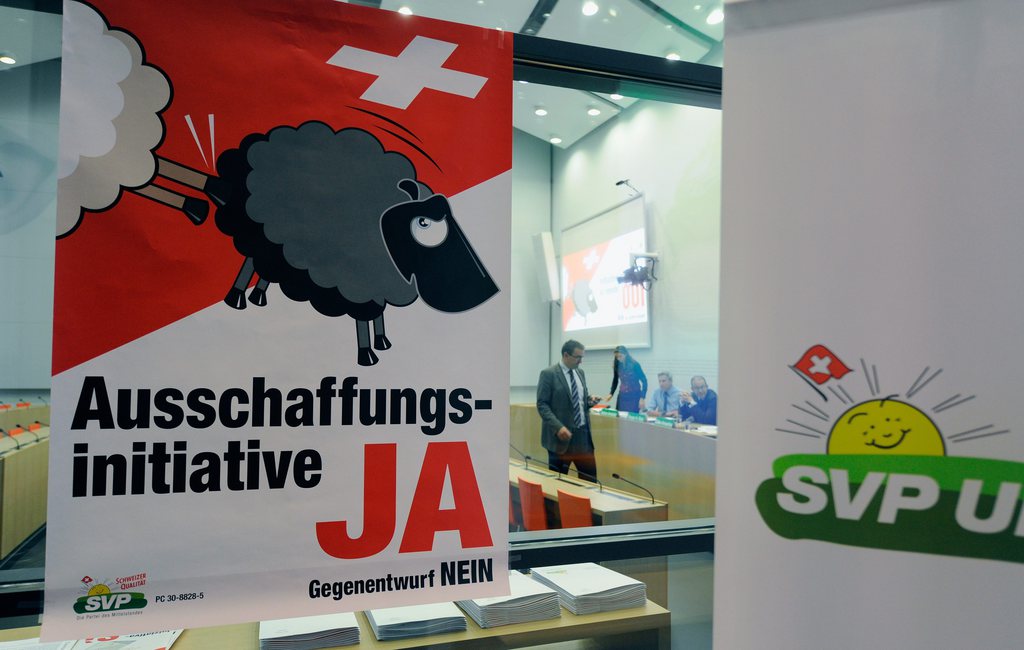

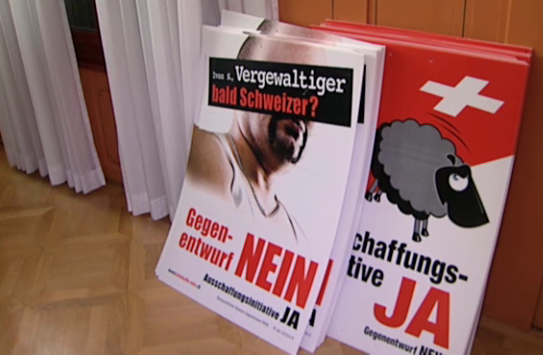

A rigorous deportation of foreign criminals: the conservative right People’s Party took this issue to the polls in November 2010.

The initiative was approved by 52.9% of the electorate. However, the initiative’s implementation soon became a source of conflict. Parliament – the legislators – struggled, rewording some passages and supplementing the law for the deportation of foreign criminals with a provision for hardship cases.

Judges would be able to make exceptions if the deportation of a foreigner would lead to a major personal hardship. Parliament approved the law last March.

The People’s Party, however, was less than satisfied and launched a new initiative in 2012 in order to exert pressure over parliament, a strategy that proved successful up to a point.

February 28 vote

The initiative is one of four issues to come to a nationwide vote on February 28. Other issues include a proposal for family tax breaks, plans to renovate the Gotthard road tunnel and a proposal by the leftwing Young Socialists to restrict financial institutions from speculation o food an agricultural commodities.

The party named it “the implementation of the expulsion of criminal foreigners (the enforcement initiative)”.

Armed with this additional political tool, the initiators demanded that the deportation initiative, including the catalogue of offences, be literally codified in Switzerland’s constitution. The offences include homicide, rape, robbery, human or drug trafficking, as well as abuse of the welfare system.

With the initiative, several specifications and amendments, such as arson and counterfeiting will be added to the catalogue of offences.

Bone of contention

“If the people and cantons want a rigorous deportation practice, they must approve the enforcement initiative,” says Adrian Amstutz, a senior member of the House of Representatives for the People’s Party and of the initiative committee.

“According to the parliament’s implementation of the law for the deportation initiative, courts would have the possibility to put aside a deportation – even in the case of the most serious offences – via the hardship clause. Current legal practices show that judges would frequently make use of this option. As a consequence, hardly any foreign criminals would be deported.”

More

An initiative to expel foreigners who commit crimes

Nadine Masshardt, a parliamentarian of the leftwing Social Democratic Party is strongly against the initiative.

“The hardship clause is necessary because it’s about the principle of proportionality,” she says.

Masshardt is concerned that judges would hardly have any room to manoeuvre.

“This contradicts our rule of law,” she says. Furthermore, the implementation initiative goes far beyond the deportation initiative. “It’s fraudulent labelling,” she says.

As an example, she refers to immigrants’ children, often born and raised in Switzerland “who will be deported to their parents’ country of origin because of two minor criminal offences. This goes way beyond what voters wanted to achieve when they approved the 2010 deportation initiative”, according to Masshardt.

This is also the main point of criticism among the broad-based opposition to the initiative.

Its opponents were in the majority in parliament (the House of Representatives: 140 versus 57; the Senate: 38 versus six). The government also rejected it.

The deportation initiative has already been specified on a legislative level, and the implementation initiative is “therefore not necessary in terms of timing nor content”, a cabinet statement said. In addition, the initiative incorporates a “narrow definition of mandatory international law”.

Separation of powers

The modern state of Switzerland was established in 1848. At that time, the country’s founders defined three levels of power: legislative (parliament); executive (the Swiss cabinet); and judiciary (The Federal Court).

These three powers are separated from each other in a constitutional state (separation of powers) in order to prevent one single organ of the state from possessing too much power.

Room to manoeuvre

Another point of criticism concerns the separation of powers. “A people’s initiative is submitted on the constitutional level. Parliament then determines the legal implementation,“ explains Masshardt.

“A referendum can be used against this.” However, with the implementation initiative, parliament in its role as legislator is ”bypassed after it already did its job”.

“This is not the Swiss way, and it contradicts our separation of powers.” She finds it inexplicable that “the party that reveres Swiss values and our political system, could abuse it to such lengths”.

Amstutz counters that constitutional law allows for initiatives “to be formulated in such a manner as to be directly applicable”. He doesn’t accept the argument that the rule of law is cancelled out by initiatives with clear provisions.

“With the provisions on speeding in traffic, parliament also defined at what speed a person is viewed as a road racer from a legal perspective, which in turn took away judges’ room for discretion.”

Free movement of people

Another concern among opponents is that approval of the initiative could lead to greater insecurity when it comes to Switzerland’s international relations.

“I believe it’s also really important that the business community speaks out against this initiative. It needs predictability of the law,” says parliamentarian Masshardt.

“The implementation initiative will violate the European Convention on Human Rights as well as the free movement of people because automatic measures would prevail and the seriousness of a crime would no longer be taken into account.”

Amstutz doesn’t understand this concern. In the free movement of people agreement, “Article 5 in Annex I allows for the terms of the agreement to be restricted for people who endanger the security or public order,” according to Amstutz.

His strongly disagrees with opponents’ argument that the automatic deportation of foreign criminals is an “inhuman kind of automatism”.

“If you want to describe someone as inhuman, then that would be the perpetrators: murders, rapists, burglars, drug and women traffickers, etc. The implementation initiative protects victims from the perpetrators,” he says.

If approved, the implementation initiative would require – just like every initiative – a change to the constitution, and as such would need the majority of voters as well as a majority of the 26 cantons.

Translated from German by Catherine McLean

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.