‘Not everyone is a potential murderer’

Following the shocking shootings in Norway, a forensic psychiatrist tells swissinfo.ch how there’s only so much authorities can do to prevent such crimes.

Frank Urbaniok, who heads the psychiatric and psychology unit attached to canton Zurich’s department of justice, also debunks several myths surrounding violent offenders (listen to audio for extended interview).

On July 22, Anders Behring Breivik, a Norwegian rightwing extremist, set off a car bomb in the government district of Oslo, killing eight people. He then went on a shooting spree at the ruling Labour Party’s annual youth camp on a nearby island, killing 69 people, most of them teenagers.

swissinfo.ch: A 32-year-old man with no history of violence calmly kills 77 people, doesn’t kill himself and then pleads not guilty to charges of terrorism. What do you make of that?

Frank Urbaniok: When we analyse what is called the offence pattern – the way somebody commits a crime – [in this case] one notices two very important elements: he didn’t kill himself, and he stresses his own belief system of being at war.

There are two ways of interpreting the fact that he didn’t kill himself. One, it’s a kind of psychosis, which means there’s a severe psychiatric disorder: as a result of delusional symptoms people are convinced of what they’re doing. We call that psychotic. But the degree of planning and his cold-blooded manner when he committed the crime is a strong argument against this hypothesis. What is much more probable is that we have an offender who has a strong sense of conviction.

You have to differentiate between psychiatric illness and dangerousness. There are a lot of personality traits that are associated with readiness to use violence but they are not psychiatric disorders.

swissinfo.ch: Breivik’s lawyer says he appears to be insane; the chief of police says he isn’t. Is he?

F.U.: I don’t believe so. Of course the lawyer claims that, but there’s strong evidence that [Breivik] is responsible for the crime: there’s the long planning period and detailed, cold-blooded behaviour.

swissinfo.ch: It wasn’t spontaneous – he didn’t get stressed and snap.

F.U.: Right. And that means you’re functioning on a high psychic level because you have to perceive what’s going on, you have to make decisions, you have to calculate the situation. That’s strong evidence against severe psychotic insanity.

swissinfo.ch: What conditions have to exist for someone to kill so many people – the majority individually?

F.U.: Normally you find a history of violence, because if there are strong personality patterns and traits they will express themselves in behaviour. But if you look at the history of this guy, you find correlations of the crime – there’s the manifesto, his theories which were developed over years.

It’s true though that normally you find violent behaviour and not only violent theory.

swissinfo.ch: One often hears that a person’s upbringing plays a central role. Breivik’s parents divorced when he was one, but a lot of people’s parents divorce and not everyone from a broken home becomes a psychopath.

F.U.: The role of childhood is a myth. If you look at the scientific research, you find that in maybe a third of violent and sex offenders you find those difficult circumstances in childhood, but you find a lot of people with the same circumstances who don’t commit offences. On the other hand in two thirds of this population we don’t find any special childhood circumstances.

Of course you are influenced by the circumstances you grow up in, but the main thing is those personality traits. If a difficult childhood were a factor for serious crimes, you’d see such a mass murder every day.

swissinfo.ch: This is the worrying thing. Maybe it doesn’t take much to push us over the edge? Are we all potential killers?

F.U.: That’s the second myth! It makes a huge, huge difference whether your probability to kill someone is 90 per cent or one in a million. That all depends on your personality traits. If you have traits that are associated with violence, you have a high probability of committing crimes. If you don’t, the circumstances have to be very unusual for you to commit a crime. To say everyone is a potential murderer is not true.

There are personality offenders and there are situational offenders. Take for example a nun with no personality traits linked to violence – she’s never had anything to do with weapons, has never been in fights or handed out provocative pamphlets. For this nun to commit a murder, you have to construct a highly specific and improbable situation. For example at a village fete she drinks a glass of water that someone has drugged, she then develops a psychosis and kills someone because she thinks the world is being run by aliens. But the problem is not the person, it’s the situation.

swissinfo.ch: Can anything be done to prevent events like this? What can friends, family and colleagues look out for?

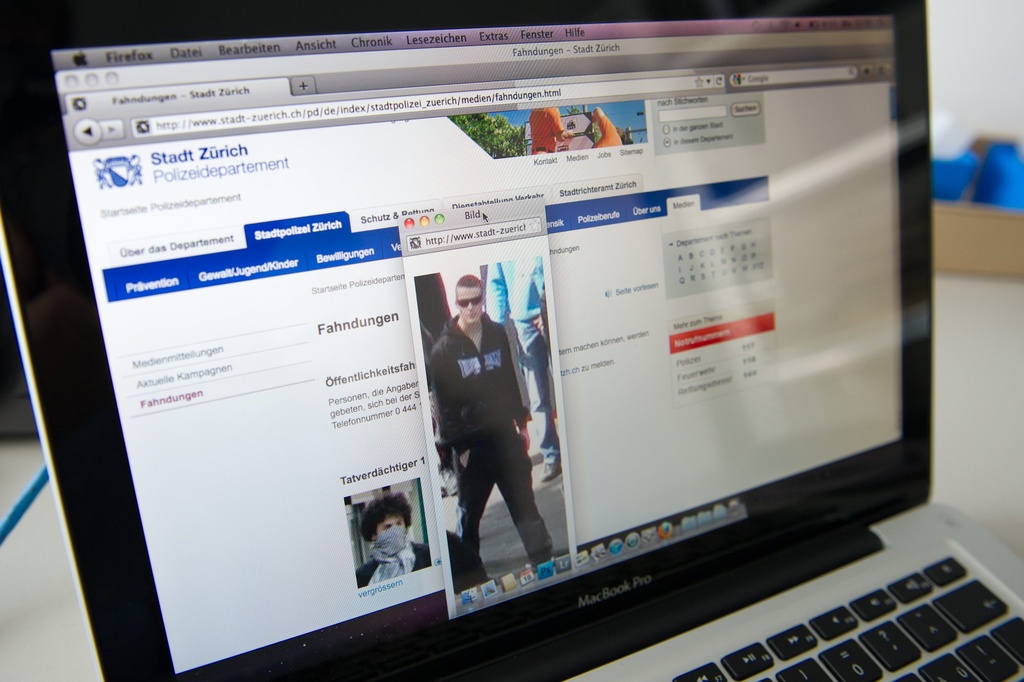

F.U.: The first thing to say is that severe crimes always have a pre-history. Always. So in theory you’ll see warning signs and can prevent crimes. But in practice, do you have access to the information and are there experts who can evaluate that information? It’s difficult if the guy hasn’t committed violent crimes before, like in this case.

swissinfo.ch: Neighbours said the usual thing of Breivik being quiet and having no girlfriends, but you can’t monitor every young man who’s never had a girlfriend…

F.U.: Of course not. Someone who plans something like this doesn’t talk about it at the baker’s or with neighbours – he develops theories and writes them down at home. So it’s not as if he didn’t come from nowhere, but his activity was hidden for years.

A lot of people write stupid or crude things, but hardly any of them are dangerous. It’s like with threats – most people who make threats are not dangerous, but it’s a question of fishing out the five per cent who make threats who also have violent personality traits – that’s when it’s dangerous.

Frank Urbaniok was born in 1963. He worked from 1989 till 1995 as a medical doctor in the Psychiatric Regional Hospital of Langenfeld/ Nordrhein-Westfalen (Germany) and from 1992 as a consultant psychiatrist and psychotherapist.

From 1992 to 1995 he set up a model ward for the treatment of offenders with personality disorders (Langenfelder Model) and coined the term “offence-oriented” therapy.

In 1995 he moved to Zurich where he first worked as an attending physician in the psychiatric/psychological service of the Zurich Office of Corrections and became head of the department in 1997.

Urbaniok continues to work as a psychotherapist and therapy supervisor and acts as court-appointed forensic expert.

He was a member of the task force set up by the Swiss cabinet for the implementation of the people’s initiative on preventive detention.

As an exponent of offence-oriented therapy, Urbaniok specialises in the treatment of violent and sex offenders.

He developed FOTRES (Forensic Operationalised Therapy/Risk Evaluation-System), a quality management and documentation tool for risk assessment of offenders, which is currently used in five countries.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.