Charlie Hebdo: too French to be Swiss

In Switzerland and abroad, the shocking massacre at Charlie Hebdo in January has encouraged a renewed interest in the satirical press. While laughter and humour may traverse cultural boundaries, caricature is based on codes that are not universal.

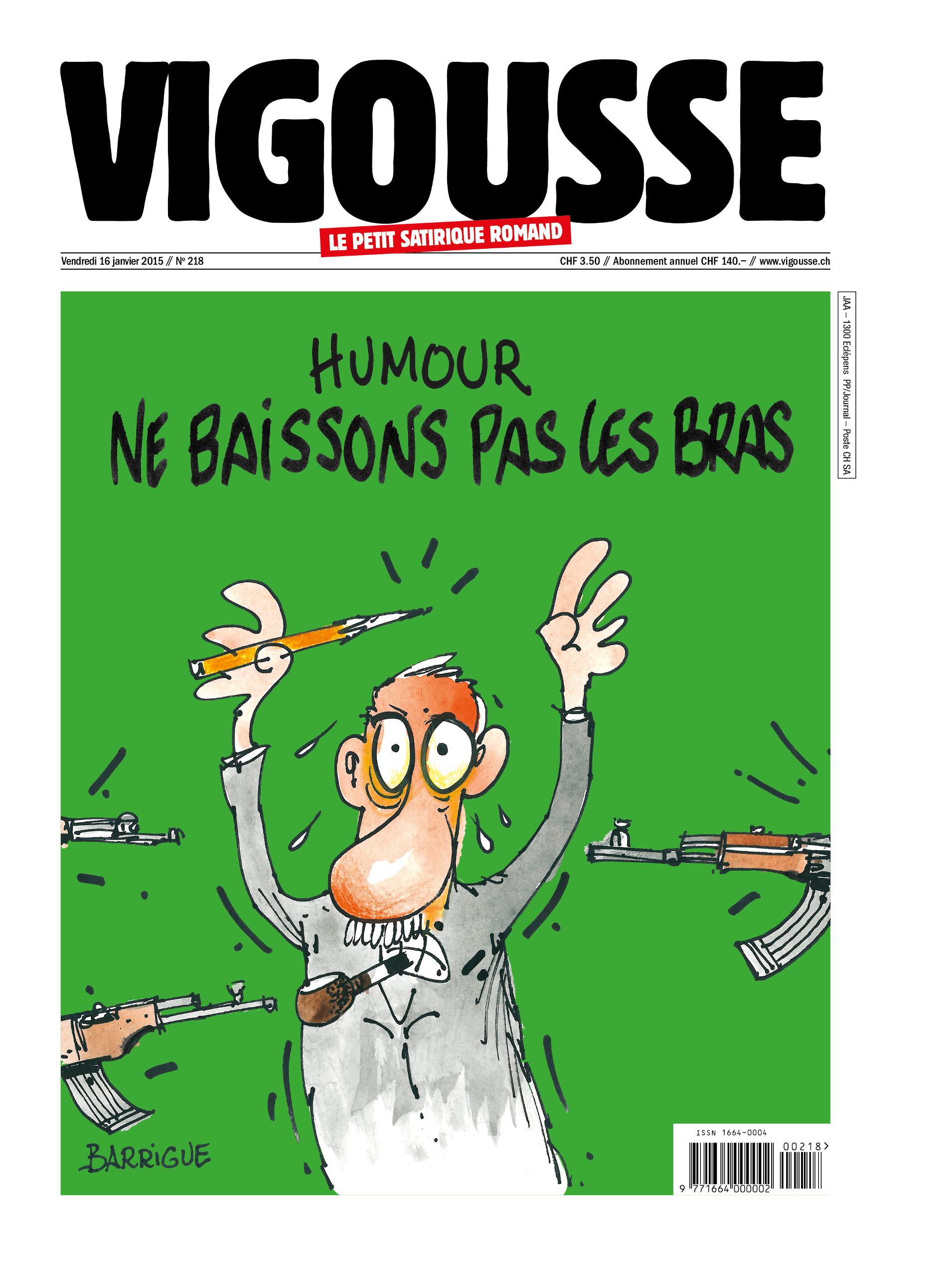

In the wave of emotion and support for freedom of the press that followed the horrific attacks in Paris, Vigousse, the Lausanne-based satirical magazine booked some 400 new subscribers.

“From the moment our comrades at Charlie Hebdo were assassinated, Vigousse received numerous testimonies and encouragement to continue its relentless pursuit of satire in all its forms,” stated the magazine, thanking its well-wishers for their support.

“Two crazy, armed men committed this horrific act and hundreds of thousands of people protested. It’s extraordinary; freedom of expression has never had so many defenders,” said Laurent Flutsch, deputy editor-in-chief of Vigousse.

For the moment, one is tempted to add…

Freedom vs self-censorship

Dominique von Burg, president of the Swiss Press Council, points out that freedom of expression has lost something of its oomph in recent years, and hopes this “tragic event will spur it on”.

“We are in a period when self-censorship is quite strong … especially in the United States, where political correctness and a type of psychosis reigns, further highlighting the courage of Charlie,” says von Burg. “To have the courage to systematically provoke in the name of free speech is really something.”

Philippe Kaenel, a professor of art history at the University of Lausanne, is more measured.

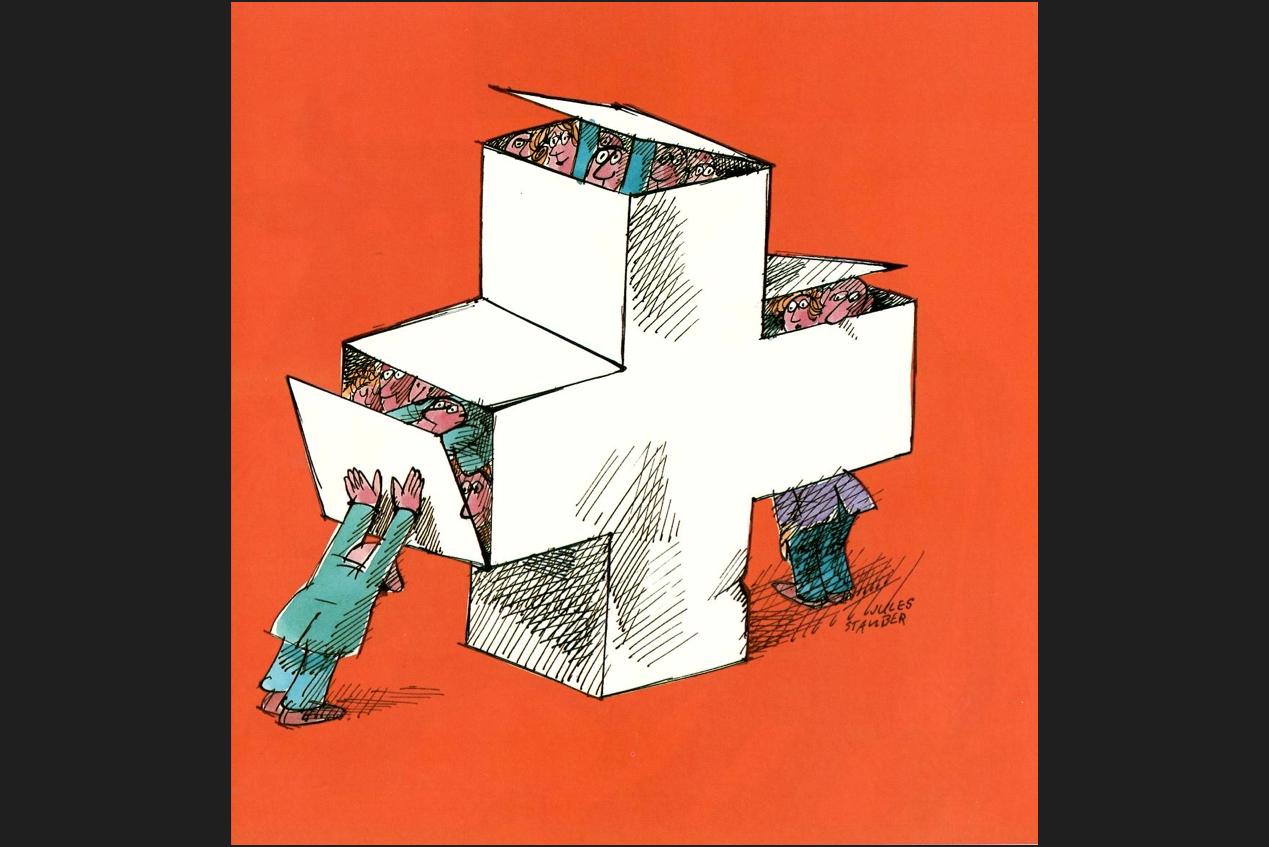

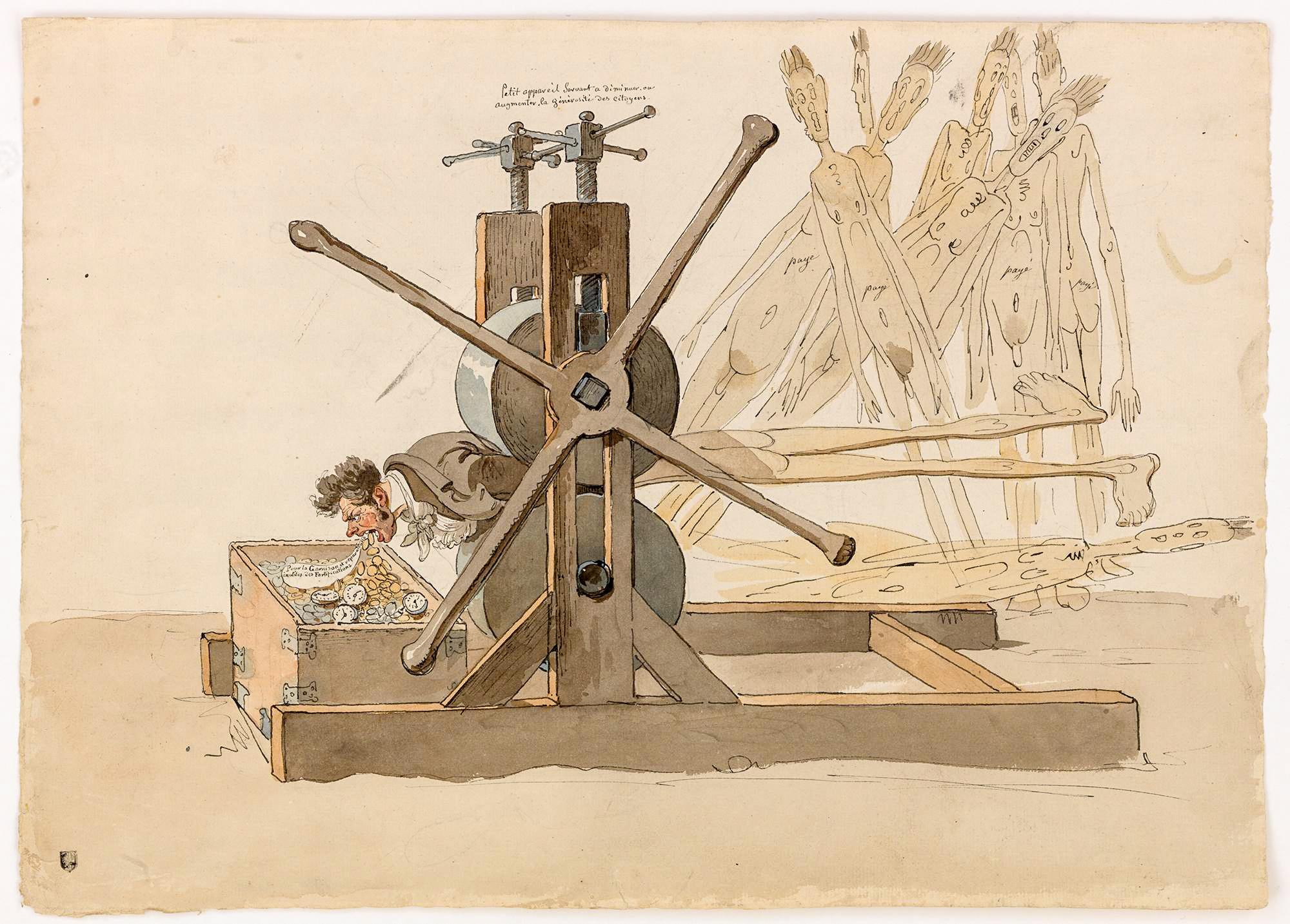

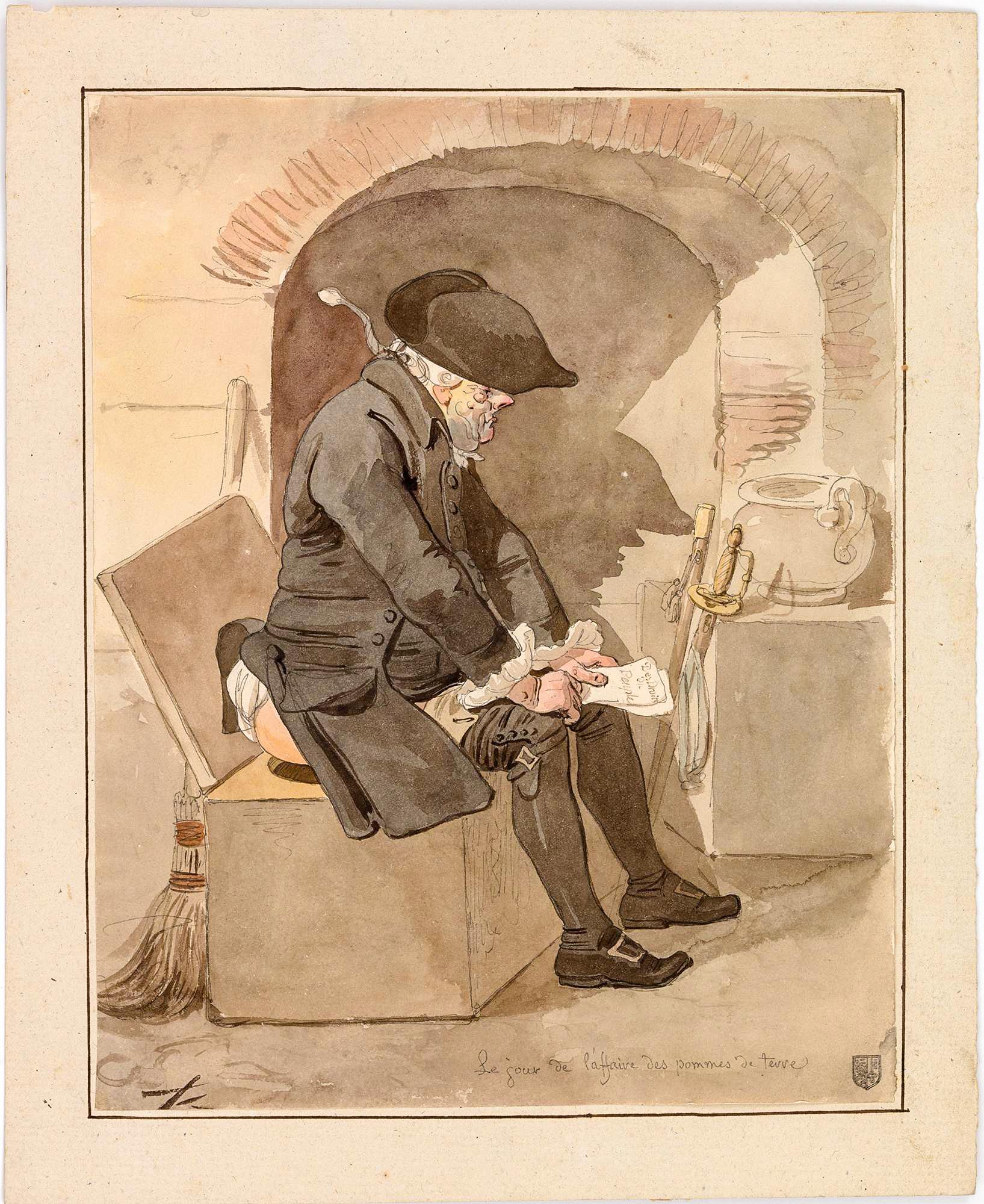

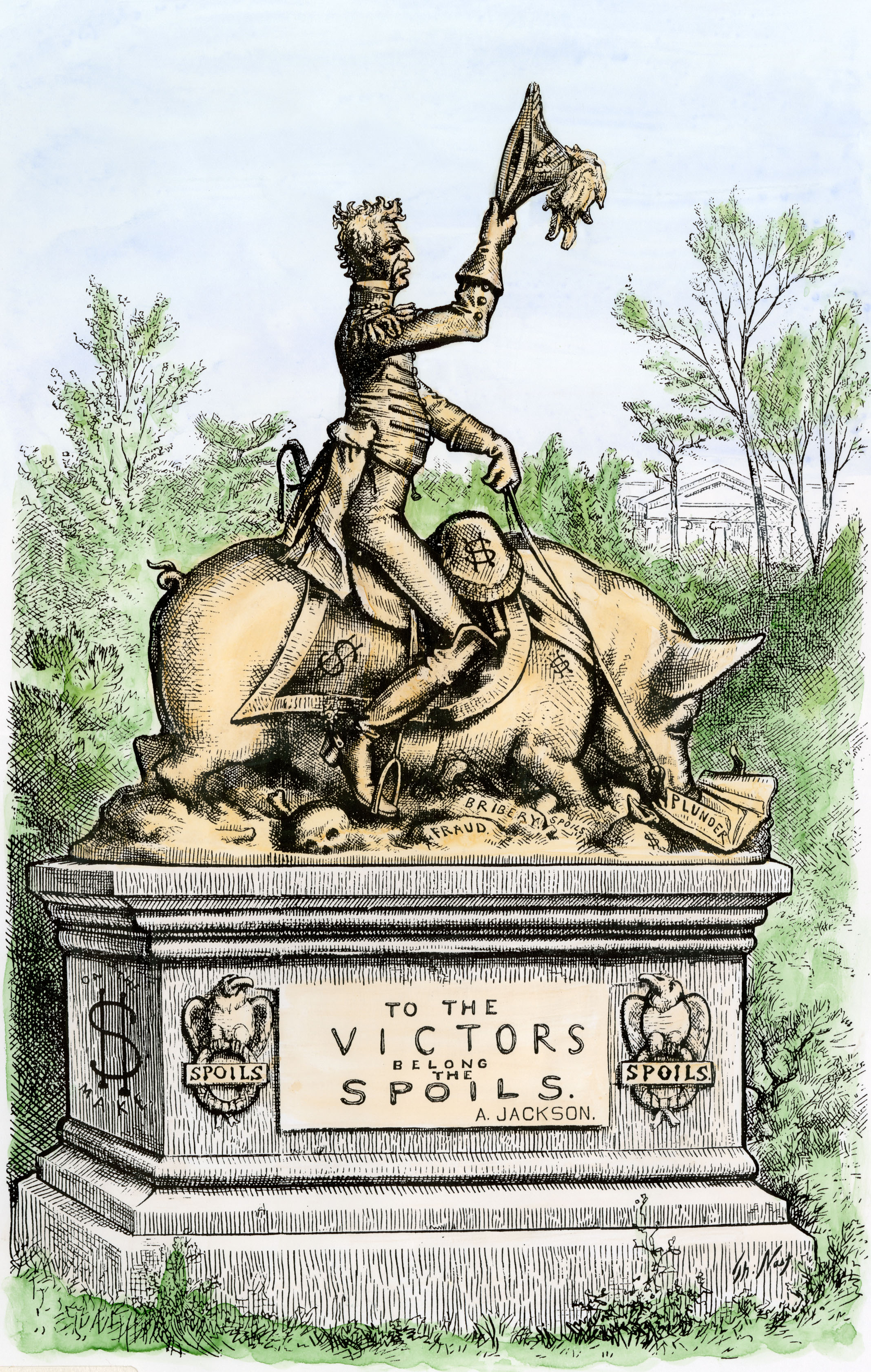

“Drawing is a handy propaganda tool because it’s a visual thought, discursive and conceptual, that can really hit hard,” he says. Still, “self-censorship is indispensable in a public body. We cannot just spontaneously say anything that we have in our hearts, otherwise it is non-reasoned debate. Applied in the media, caricature works … by rattling common references.”

In the publications that use caricature, the artist takes on the role of commentator and must submit drawings (in general they submit several) which will then be accepted or rejected by the editors. Vigousse sometimes refuses to publish certain cartoons, says Flutsch.

Online, cartoons are published in a “haphazard fashion”, and disconnected from the original context, says Kaenel. Charlie Hebdo is a Parisian weekly and is not intended to be read by everyone, he says. More precisely, Charlie Hebdo belongs to a French niche, “slightly anarchistic” press which previously in the 1900s had displayed an “extreme ferocity”, something that wouldn’t happen today, he says. In Switzerland, Vigousse (which often publishes cartoons by several of Charlie Hebdo’s satirists) was created by the French cartoonist Barrigue, and is a kind of off-shoot of French satire, with nuances.

Denounce not mock

Vigousse did not publish the Mohammed caricatures when they came out “because to us, they didn’t seem very funny and it would have been copying”, says Flutsch.

Freedom of expression is guaranteed by the constitution, and the Federal Court requires that satire be recognisable and not exceed “by an intolerable measure the limits of its own nature”. The Swiss Press Council’s guide to satire notes that ethics also applies to satire. In 2006, ruling on the caricatures of Mohammed first published by the Danish Jyllands-Posten, the council said that it should be possible to illustrate the “serious conflict” between free commentary and respect of religion “with carefully defined quotes in images”; it considered the publication of 12 caricatures without commentary problematic.

“Contestation and caricature are our drivers. A drawing is a denunciation, not just mockery, but the idea of shocking a community is not a criteria. We are very careful not to be unnecessarily ‘trashy’ or scatological. We can be nasty without being vulgar, fierce in the finesse,” he adds.

Some Francophiles say that when it comes to satire, German-speaking Switzerland is traditionally more consensual and “nicer”. Does Marco Ratschiller, editor in chief of the leading German-language satirical paper, the Nebelspalter, agree?

“Provocation and insolence are an option, but we can also say a lot between the lines, not nicer but sometimes more subtle,” Ratschiller says. “The political system in Switzerland “is also very different to the French. The decision-making process, consensus, direct democracy, etc.. It has everything but is not as strong and powerful as in neighbouring countries.”

Different satirical culture

Ratschiller talks of a cultural difference. “French satire [in Switzerland] – and even more so, in France – is more aggressive, more in-your-face than in German-speaking Switzerland and Germany. In our papers, investigative journalism is separated from commentary or caricature, which are often closely related in the Francophone media,” he says.

While most of the French-language dailies employ cartoonists, the Tages-Anzeiger is the only German-language paper to do so; it publishes an editorial style cartoon each day. The weekly NZZ am Sonntag regularly commissions cartoons by the French-speaking Chappatte. But that’s about it.

For Ratschiller, French-speaking cartoonists hold a special journalistic status. “That is not the case here [in German-speaking Switzerland], and it’s a shame, because it deprives the younger generation of a means to learn the art,” says Ratschiller.

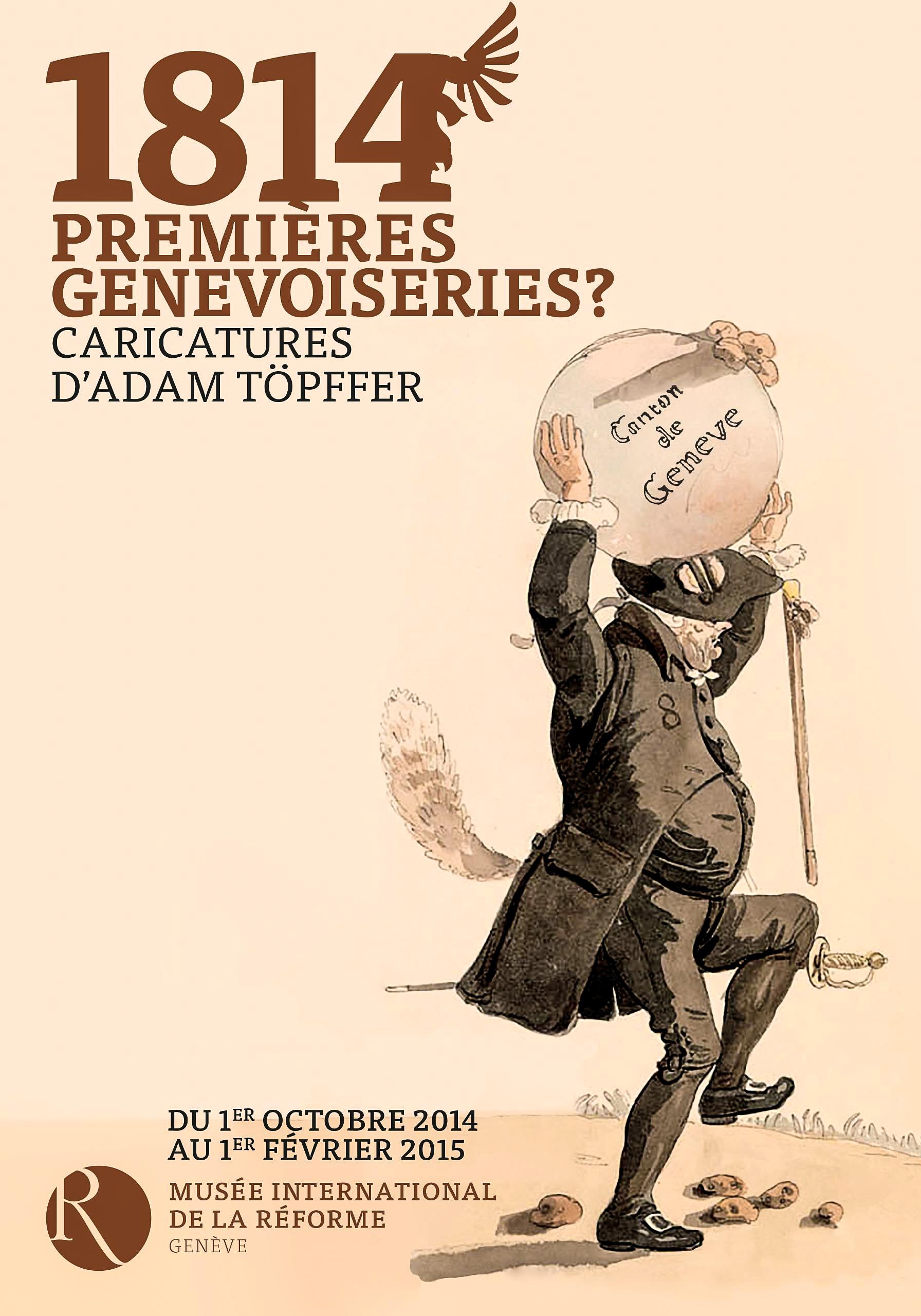

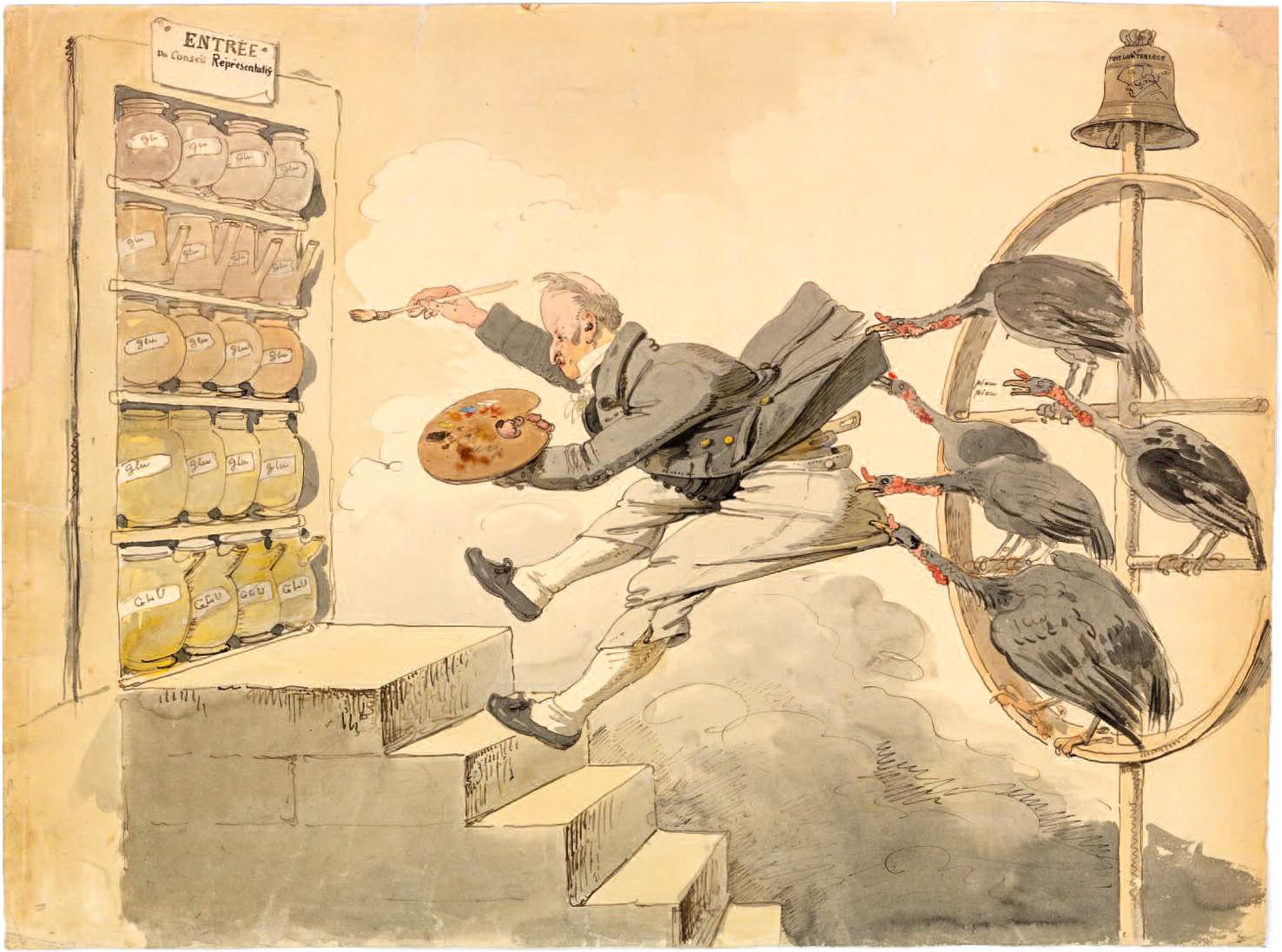

In general, the Francophone cultural sphere has many outlets where artists can train and contribute to the richness of caricature, a genre which struggles to find its place in Germanic literary culture.

Despite this, the Nebelspalter can lay claim to being the oldest illustrated journal in the world, and has been published every month since 1875.

Politically, Switzerland is also well placed to welcome satire because censorship, at least in theory, does not exist.

“Free speech has been guaranteed in the constitution since 1848,” says Kaenel. “Swiss caricature is not as spectacular as the English or French versions, it has never had the likes of Daumier. But for the last 40 years, there have been several first-rate artists who have also responded to international events.”

Major Swiss satirical publications

The weekly French-language Vigousse (12,000 print run) was founded in 2009 by Barrigue (son of the French cartoonist Piem) with Laurent Flutsch and Patrick Nordmann.

The monthly German-language Nebelspalter (21,000 copies) was created in 1875 by Jean Nötzli in Zurich and inspired by England’s Punch.

The monthly La Tuile (2,500 copies) was founded in 1970 in canton Jura by the pamphlet publisher Pierre-André Marchand.

The bimonthly La Distinction (1987) is a critical review of social and political themes, art and literature, culture and food, which each year awards the mayor of Champignac’s Grand Prize for the most ridiculous phrase uttered by a public figure.

The bimonthly Il Diavolo (4,000 copies) was created in 1991 in Ticino by members of the Autonomous Socialist Party, co-founded and edited by the cartoonist Corrado Mordasini.

(Adapted from French by Sophie Douez)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.