Archaeologists in Switzerland prepare for post-war Syria

As death and destruction continues in Syria without an end in sight, three archaeologists tell swissinfo.ch of the importance of preserving the nation’s cultural heritage, how the Swiss could help train people to do this, and the role played by Switzerland as a safe haven.

What goes through an archaeologist’s mind when they see historic sites or museum objects that are thousands of years old being blown up or demolished?

“As a Syrian archaeologist, I’m obviously very, very sad. This is really a tragedy for our cultural heritage,” said Mohamad Fakhro, a lecturer at the University of Aleppo, the worst-hit city in the civil war.

“But my first reaction when I hear about the Temple of Baalshamin in Palmyra or other acts of destruction is focusing on how we can reconstruct them. We’re archaeologists not politicians or soldiers. Our goal, our job, is to protect the cultural heritage.”

That’s the motivation behind a recent talk given in Bern by Fakhro, Mohammed Alkhalid, a post-doc student of Near Eastern Archaeology at the University of Bern, and Cynthia Dunning, director of ArchaeoConceptExternal link, an independent Swiss company that finds solutions for problems encountered by archaeologists and heritage managers.

In their TEDx presentation, they focused on the work of ShirinExternal link (Syrian Heritage in Danger: an International Research Initiative and Network), which brings together experts in various fields to support governmental bodies and NGOs in their efforts to preserve and safeguard the heritage of Syria. Dunning is an advisor to Shirin’s international committee.

“My hope is that my Swiss colleagues in the cantons and universities or even in private companies will also participate in this reconstruction for the future, helping us find places for people to do some training,” Dunning told swissinfo.ch.

For its part, the Swiss Federal Culture Office has played a central role in safeguarding the transfer of cultural propertyExternal link for many years.

“The safe haven is very special,” said Dunning, who was responsible for the archaeological service of canton Bern from 1998 to 2010.

“Swiss law allows the Swiss government to bring in cultural objects from countries at war. That’s what happened in Afghanistan: the Afghan cultural goods came to Switzerland and will be kept here for as long as the war continues in Afghanistan. Other countries don’t have that. It’s very special.”

However, it’s not as simple as Switzerland offering to look after objects and archaeologists then sending them over. “The government in Syria must say it wants to protect its cultural goods and must ask Switzerland to organise a safe haven for its objects. And that’s not the case. It hasn’t asked,” she said.

Fakhro says he has tried to contact his colleagues in the directorate of antiquities and museum in Damascus to make them aware of the Swiss safe haven, but he says the law in Syria prevents them from taking advantage of it.

“It’s completely forbidden. They say that if they were to do something like that, it would mean the government is weak,” he said.

“We asked them about [bringing to Switzerland] objects found in Turkey or Jordan that belong to Syria, but they say that’s not allowed either. It’s politics.”

International effort

For Dunning, destroying a country’s past means destroying irreplaceable memories, “so we have to work to try to find methods that somehow impede that by getting people involved in reconstructing the future in these countries – Afghanistan, Syria, Iraq or wherever”.

It’s an international effort, because, as Alkhalid says, the whole world is a victim of the destruction of cultural heritage. “Cultural heritage belongs to all of us. This is a global issue not just a Syrian issue. We’re all affected.”

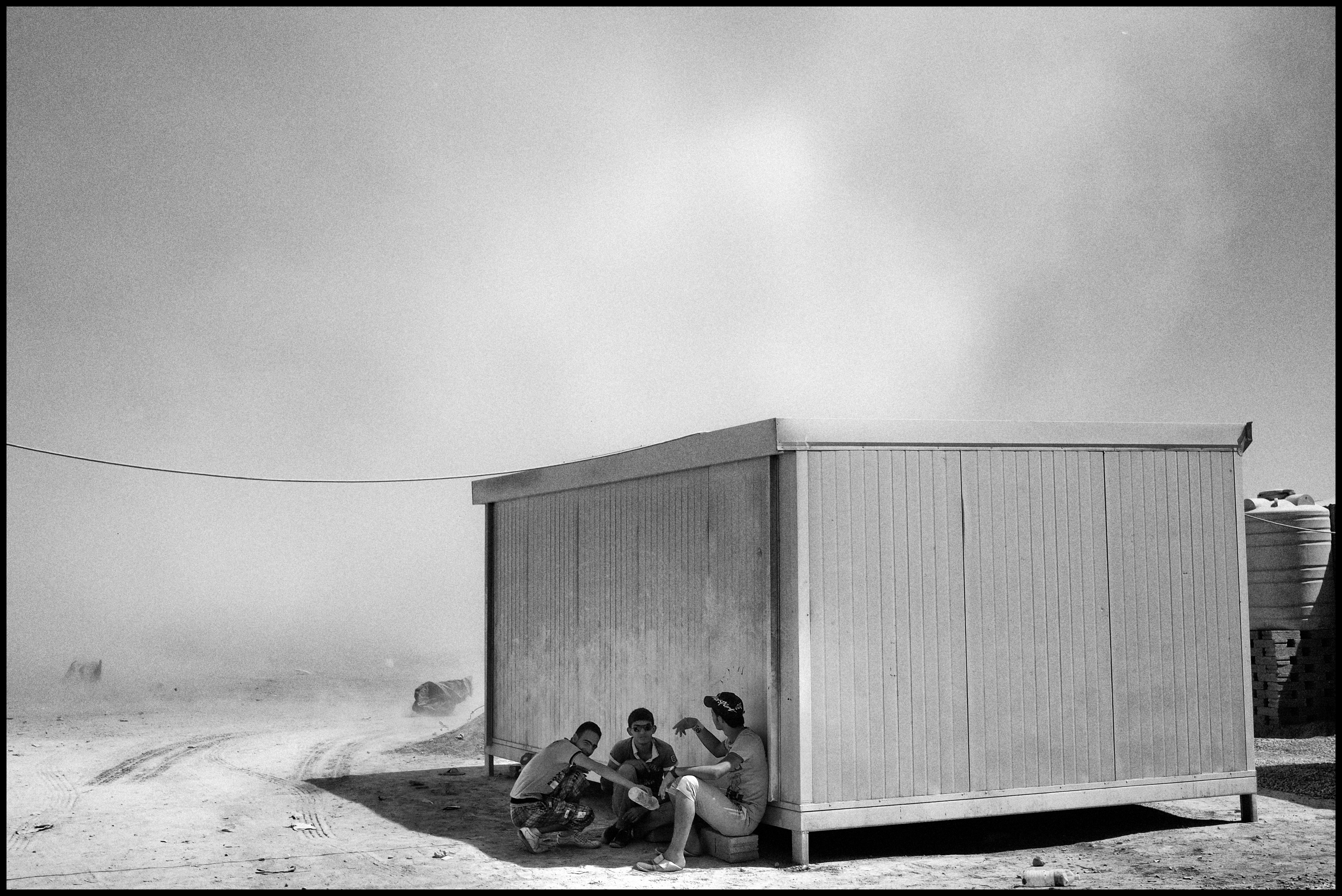

The civil war in Syria, which has claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and displaced millions, affects museums and archaeological sites, either as collateral effects of fighting or through looting and intentional damage.

“It’s not just Palmyra – there’s destruction of cultural heritage all over Syria and many illegal excavations everywhere,” said Fakhro, who is also director of the department of excavation at the directorate for antiquities and museums in AleppoExternal link.

“This is the problem. You can’t reconstruct illegal excavation because if you destroy the layers in the tiles or the archaeological site, you lose it forever. And of course when you have illegal excavations you have trading for antiquities – in Europe and around the world.”

‘There’s always hope’

Many government institutions and NGOs have launched initiatives to protect heritage sites, to register destructions and lootings and to prevent trade of stolen artefacts on the international art market.

Less developed are the initiatives to train experts and specialists that will be required after the war is over. Museums have to be reconstructed and recreated, artefacts restored, archaeological sites cleaned for mines and other traces of the war, heritage sites relaunched and prepared for visitors.

Dunning says that while the large international organisations such as UNESCO, ICOMOS (the International Council on Monuments and Sites) and ICOM (the International Council of Museums) can use their power to safeguard cultural heritage, “they have one disadvantage”.

“The only partners they speak to are government partners. They can’t speak to other people who are not in the government and who may be in the opposition or whatever. And that’s a chance for the NGOs, who can get people together – from the opposition, from the government – who are all archaeologists and who can all work together. They don’t have problems talking to each other although they might have different religions or political ideas.”

As for the future, who knows? “We can only be optimistic!” said Alkhalid. “Although personally I’m not so optimistic. But there’s always hope. We hope that the war and the tragedy in Syria will end and that after the war we can do something for the cultural heritage.”

Fakhro is also realistic. “It’s hard to say what the future will bring, but we have to do our best to prepare materials, a team – whatever – for the post-conflict reconstruction and preservation. Unfortunately until now the picture is dark, but without hope you can’t work.”

What was your reaction when you saw or heard of the destruction of ancient temples in the Middle East?

Shirin

Shirin (Syrian Heritage in Danger: an International Research Initiative and Network) is an initiative of the global community of scholars active in the fields of archaeology, art and history of the Ancient Near East.

It brings together a significant proportion of those international research groups that were working in Syria prior to 2011, with the purpose of making their expertise available to wider heritage protection efforts.

The main purpose of Shirin is to support governmental bodies and non-governmental organisations in their efforts to preserve and safeguard the heritage of Syria (sites, monuments & museums). It will take account of, and respond to, the needs of Syrian colleagues and authorities regardless of their political, religious or ethnic affiliation, in particular with respect to emergency steps and measures.

The Institute of Archaeological Sciences of the University of Bern is the only Swiss institution that conducts research and provides the possibility of academic studies in both the fields of archaeology and philology of the Ancient Near East. It is involved in field activities in Syria, Turkey and Turkmenistan.

(Source: Shirin)

War in Syria

The armed conflict in Syria began in March 2011 with anti-government protests before escalating into a full-scale civil war between forces loyal to President Bashar al-Assad and those opposed to his rule – as well as jihadist militants from so-called Islamic State.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, eight million people have been displaced inside Syria, 4.5 million people live in besieged cities and hard-to-reach areas and 4.5 million refugees live in neighbouring countries and beyond.

1.5 million people have been injured and 250,000 have been killed.

TEDx

TED (technology, entertainment and design) is a global set of conferences run with the slogan “Ideas Worth Spreading”. These usually take the form of short talks of around ten minutes.

TEDx events are planned and coordinated independently, under a free licence granted by TED.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.