Can participatory democracy raise voter turnouts?

Biel (Bienne, in French) is best-known for being the capital of Swiss watchmaking and for being the biggest bilingual town in the country. But it has another claim to fame: its citizens are among the least likely in Switzerland to get out and vote. Local authorities want to change this with a more participative approach.

We live in a golden age of popular rights and participation. Forums, roundtables, and politically-themed debates are constantly being organised in Switzerland and beyond – notably in neighbouring France.

But while across the border the ‘gilets jaunes’ are demanding the right to initiate referendums, local leaders in Switzerland are trying to revive a sense of civic impetus in citizens.

It’s needed: in Biel, over half of citizens have been losing interest in politics for some time now, and participation rates over the past 25 years are far from impressive.

As a result, authorities in the bilingual city want to reform the municipality’s foundational document, its “constitution and legal heart” that dates in its current form dates to 1996, and they want to do this by “taking the pulse of the population”.

Will it work? A recent public meeting in the city tried to sketch an initial response.

Recalibration of democracy

Some 100 politicians and voters gathered recently to listen to Biel’s Social Democrat mayor, Erich Fehr, who outlined the path to be traced to make the local community feel more concerned – or, even better, involved – in politics once again and to share with authorities the task of governing the town of 56,000.

“We’re living through a recalibration of democracy,” opens Fehr. But Biel is the regional cantonal champion when it comes to abstentionism. To counter this, “we need to ensure that in future, citizens cast their votes on issues that really matter”.

For example: the yearly vote on the city’s budget could be scrapped in the coming years, or at least for as long as tax rates remain the same. On the other hand, the number of signatures to launch a people’s initiative referendum could be lowered.

The participatory atmosphere in the air in Biel also raises the prospect of further innovations: the right to launch a motion, for example, the right to hold non-binding consultation votes, or to bring decision-making closer to the city’s neighbourhoods.

Some citizens, chosen at random, have already raised objections, desires, and criticisms during the drafting period for the new administrative charter.

And one issue that came up was the question of the many foreigners living in Biel, and whether they too might have a say in local affairs in the near future. Each resident, whether eligible to vote or not, whether from the city or from elsewhere, should have the right to political expression, many say.

The new text should also require greater transparency from local politicians, for example when it comes to possible conflicts of interest, as well as demanding that they pay more attention to the type of information they address to the population.

However, one issue that will not be anchored in the municipal constitution is the question of struggling local media, and a possible system of public funding to help them. “The job of supporting media falls on the federal level, so that a balance between the country’s linguistic regions can be maintained,” says Fehr.

Sliding trend

The 50- year-old mayor is clear that the age of paternalist politics, where roles were clearly defined between those governing and those governed, is over. He sees this clearly from his town hall office, where as an adolescent he already sat as his father Hermann oversaw the town’s affairs from 1976 to 1990.

The political energy of those earlier decades has given way to a disinterest best summed up by the large abstentionism for national and local votes, a figure often reaching 70%. Between 1991 and 2012, average turnout rates in Biel were between 2.7 and 15 percentage points lower than elsewhere across the country, depending on the nature of the vote.

Several reasons have been put forward to explain the disconnect between people and their politicians: the population in Biel is younger than elsewhere, there is no higher education university in the city, and the multilingual nature of the town doesn’t help a close reading of vote information.

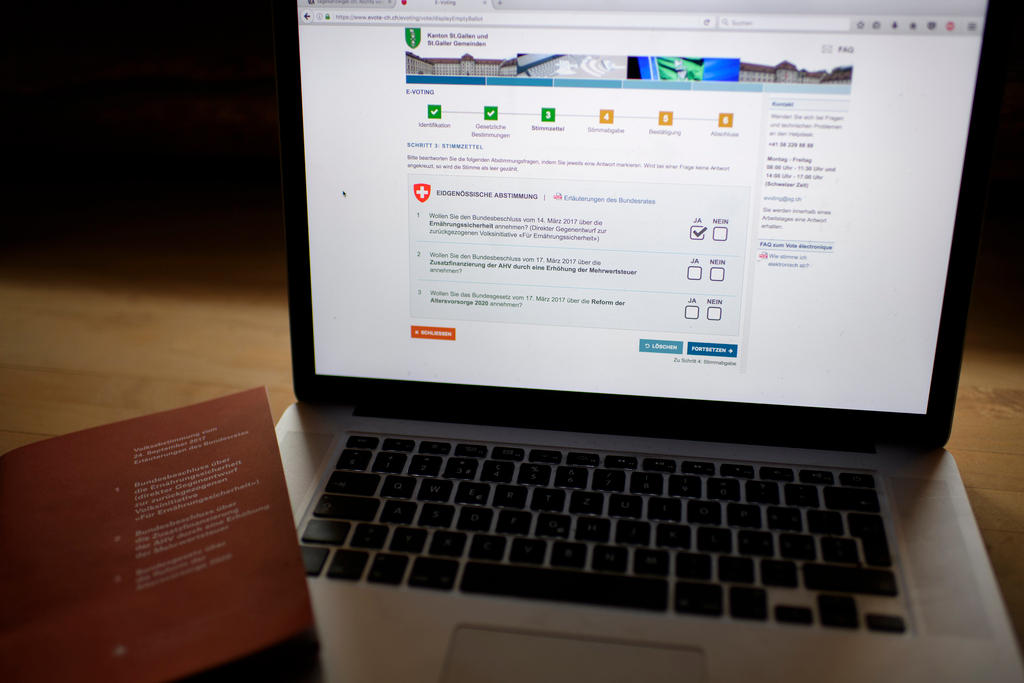

Ideas to boost voter turnout have also been examined: simplifying electoral information, e-voting, SMS reminders, installing new letterboxes for postal voting. And last November 25, some four of every ten Biel voters approved this year’s budget – a jump from three out of ten a decade before.

Leap into the unknown

Yet the concrete application of direct democracy, whether in Switzerland, France, or elsewhere, remains an uncertain exercise; it is neither an exact science nor a guaranteed good, but rather always remains a work in progress.

“There are new proposals in the new constitutional document, but not thousands of them. This framework doesn’t lend itself to ultimate creativity. We are moving somewhat into the unknown,” says Barbara Labbé, Biel’s chancellor, who has worked on the project for two years.

Her municipal legal services will now continue to collect, via a questionnaire handed out at the start of the redrafting process, the final grievances and comments of citizens on the new ‘constitution’ until the end of April.

Will the locals play along? “I hope so,” Labbé says. “I hope that the residents who don’t have the right to vote her will respond positively to the invitation. We would also like to know if the concerns we have collected from citizens over the past two years have been translated into the drafting process – not an easy task,” she says.

Participation in the project thus far has been mixed: most people at the recent meeting in Biel were local politicians, already involved in politics. Scattered among the crowd were some of the 80 citizens – drawn from a group of 600 – who had previously given their input into the elaboration process. Some 1,200 further citizens have provided feedback via a questionnaire.

Of course, the real figure remains to be seen: how many voters will turn out to give their say on the final version of the document when it is put to the public in May 2020?

More

Swiss watchmaking city tries to shed gritty reputation

Adapted from French by Domhnall O’Sullivan, swissinfo.ch

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.