Switzerland’s Silk Road is a slow one

The worms and the people behind Swiss Silk have something in common – both are motivated. For the silkworms it’s a matter of eating enough mulberry leaves to complete their lifecycle. For the producers, it’s a make or break moment to keep their tiny sector alive.

“When they eat, it sounds like fine rain. It’s the loveliest sound. The older the worms get, the better you hear it – especially when they’re all eating and you stand perfectly still,” says silkworm breeder Manuela Friedrich. She’s one of about 30 producers behind Swiss Silk, established in 2009 to revive the delicate industry – which thrived in Switzerland between the 17th and 19th centuries.

Swiss Silk president Ueli Ramseier – also a textile engineer and farmer – lights up when he talks about the product.

“I’ve been into silk since 1985,” says Ramseier, who once worked in the silk-printing industry. His travels have also taken him along the legendary Silk Road. Like many Swiss Silk producers, raising silkworms is something done alongside other agricultural pursuits – in his case, growing hazelnuts.

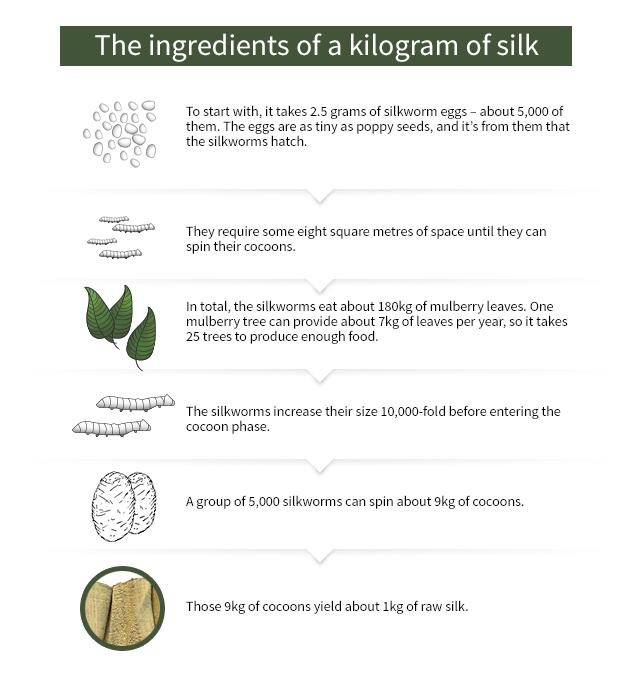

Ramseier is one of the four advanced cocoon producers in the group; together they account for about 85% of the yield. There are also seven beginners plus a number of hobby producers, like school groups. One producer focuses solely on growing mulberry trees – no small task considering how many leaves are required to feed the hungry horde of silkworms. In fact the worms would eat just about any vegetation, but only the mulberry leaves can provide the right juice for making silk.

Medium quality

In 2014, Swiss Silk managed to spin about 20kg of raw silk – more than double the yield of 2013. The goal is 100kg/year within the next five years; the ultimate goal would be a ton per year. In comparison, China produces 100,000 tons of raw silk annually.

Patrick Genoud of S.O.L. Silk Opportunities is Switzerland’s biggest silk trader. He sources his material from major producers in China, Brazil and India. His firm is a supporting member of Swiss Silk.

“We admire their determination. After [just a few] years, it seems they are indeed able to produce a decent quality of raw silk,” says Genoud, who gave a presentation at Swiss Silk’s most recent general assembly. “I tried to give them a glimpse of the world market.”

Ramseier notes that in terms of quality, Swiss Silk is medium grade. On a scale of E (poor) to 6A (top), the first skeins of Swiss silk were about a 2A or 3A – nice enough to make a necktie or a scarf, but not suitable for something as fine as crepe de chine.

Genoud agrees, explaining that it’s not even possible to grade it formally as the yields have been so small. That is, the quality control tests would destroy about three kilos’ worth – not sustainable when there are only 20 kilos in total.

According to Genoud, the world’s best silk comes from Brazil. China, on the other hand, has been struggling. In recent years, its silkworm sector has had to relocate – and the new region isn’t as conducive in terms of climate.

Indeed, the silkworms are very sensitive. They can fall victim to bacterial or viral illnesses due to insufficient hygiene. Too little food – or irregular feeding – can also cause problems.

“The speed of development is very fast, so your time to react is quite limited,” Ramseier explains. Pesticides are another issue; Ramseier holds off on rearing his silkworms until his neighbours have finished preparing their orchards for the spring. Though not completely organic, Swiss Silk producers don’t use any growth hormones or antibiotics.

More

Switzerland produces its own silk

CHF12/hour

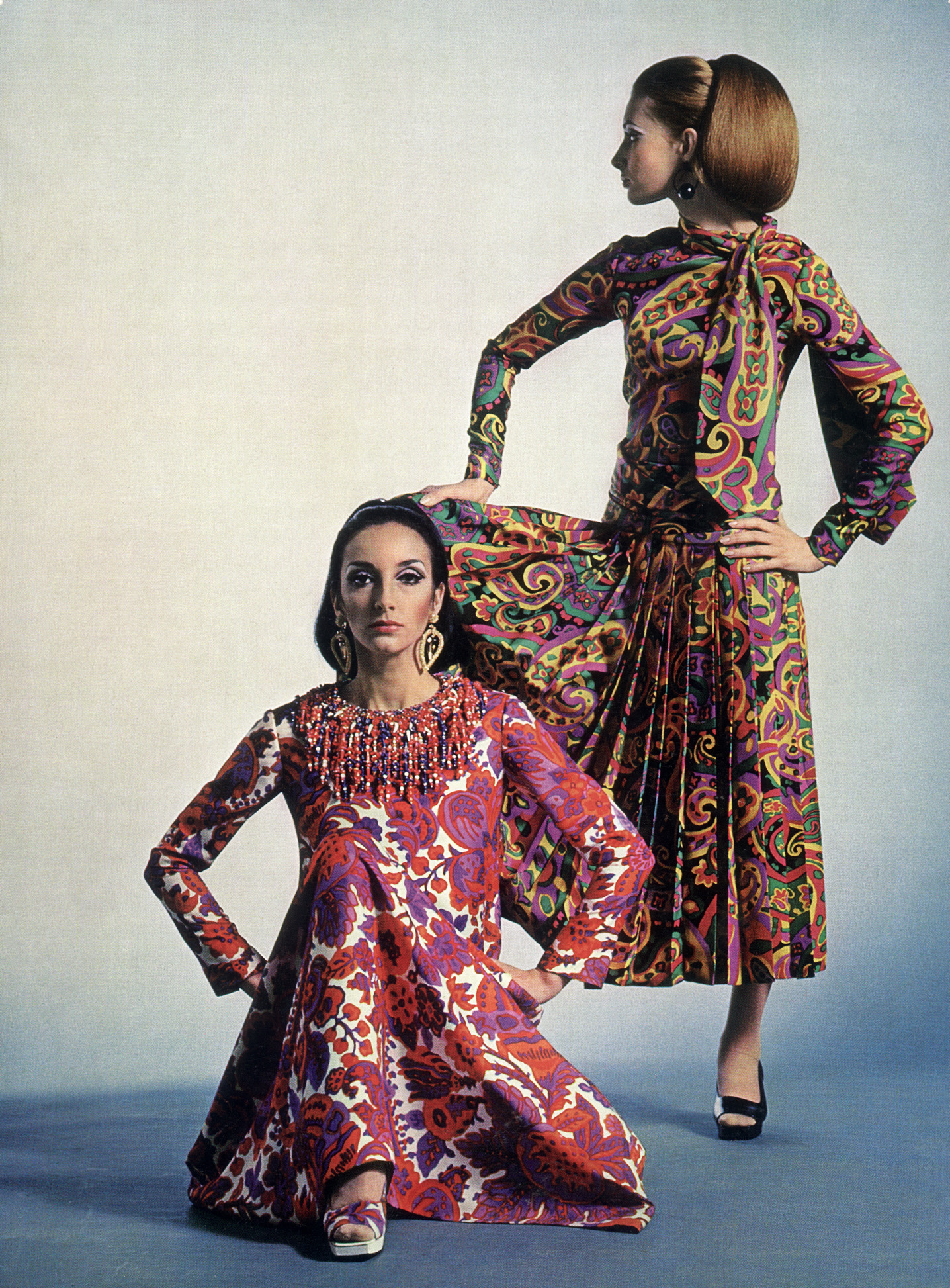

Last autumn, Swiss textile firm Weisbrod-Zürrer took the first big batch of Swiss Silk’s raw material and created about 150 ties and 40 scarves. Available in blue, brown and grey, they’re sprinkled with little white moths.External link The ties cost CHF150 ($154), the scarves CHF220. In comparison, Weisbrod’s other ties sell for CHF89, its silk scarves for CHF89-178.

Despite the extra expense, sales of the Swiss Silk line have been good. As of April 2015, the scarves were nearly sold out, and two-thirds of the ties had found new owners. Weisbrod-Zürrer and Ramseier are now looking into the next collection – to be ready by November. Meanwhile, another company is interested in making knitted scarves.

“The idea of reintroducing silk in a high-price island like Switzerland made people sceptical, but we gave it a chance. We figured if the farmers were doing it as an alternative activity, it could work – so we decided to support it and see,” recalls Genoud.

Although the Swiss silk costs about six times more than its foreign counterparts, the producers’ earnings are quite modest. Ramseier says last year, he only earned about CHF12/hour for his silk business.

“For those farmers willing to invest the time, there’s a chance to have a profitable income,” Ramseier says. “However, we’ve decided that if we don’t get at least CHF20/hour, then we will stop the programme.”

Increasing income

At this year’s general assembly, Swiss Silk talked about how they could increase their earnings.

“We have a lot of people who visit our farms, and they always want to buy something – from cocoons to ready-made products,” says Ramseier. “This would give us the chance to earn more income on our farms.”

Embroidery floss is another potential product. The target group for this would be the makers of traditional Swiss folk costumes – who would likely appreciate having Swiss silk to embellish their garments with. And in the medical sector, there’s a market for silk to make things like artificial spinal discs.

“For them it would be important to be able to trace their raw products. We could do that because we know every farmer,” says Ramseier.

Even if Swiss Silk achieves its production goals, the volume will be too small for someone like silk trader Genoud to peddle it around the world. Instead, its limited quantity will likely ensure that it remains an exclusive niche product.

“I’m sure they’ll find niches where they can sell raw silk even at a very expensive price compared to the international price standards, but the people will like it,” Genoud predicts.

Zurich-based Fabric Frontline, which specialises in silk scarves, currently sources its silk from Italy. They haven’t had the opportunity to examine Swiss Silk’s wares yet.

“Swiss silk would be very interesting for us,” says spokeswoman Vesna Mitrovic. “Of course the quality and availability would have to be consistent.” If Swiss Silk passes muster there, it could find itself in the international spotlight. Fabric Frontline’s most famous customer is British designer Vivienne Westwood.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.