Why do we need the Global Compact for Migration?

Over 160 United Nations member states have formally adopted an international agreement in Morocco that promises a better, more coordinated approach to migration. Why is such a pact needed? Why is it so controversial, and why is Switzerland, which helped shape the accord, not attending?

On Monday, heads of state and government ministers from 164 countries publicly confirmed in Marrakech their commitment to the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular MigrationExternal link, a multilateral accordExternal link which was concluded under UN auspices earlier this year.

The final 31-page document, intergovernmental conferenceExternal link on December 10-11, and endorsement ceremony are the culmination of almost two years’ intensive negotiations, involving states, members of civil society and the private sector, and facilitated by the Mexican and Swiss ambassadors, Juan José Gomez Camacho and Jürg Lauber.

Why do we need a global migration pact?

According to the UN, there are around 258 million migrants in the world todayExternal link. This figure is expected to grow due to globalization, easier communications, transport and trade, as well as rising inequality, demographic imbalances and climate change. MigrationExternal link, the UN says, provides huge opportunities and benefits for the migrants, host communities and communities of origin. But when migration is poorly organised, it can create major headaches and therefore needs to be safer, more orderly and regulated.

The pact gained momentum after the migration crisis in Europe in 2015, which saw the biggest influx of refugees and migrants since World War Two. It is the fruit of earlier human rights and development treaties and initiatives like the Global Forum on Migration and DevelopmentExternal link, and stems from a political commitment known as the “New York Declaration for Refugees and MigrantsExternal link”, adopted unanimously in 2016 by the 193-member UN General Assembly.

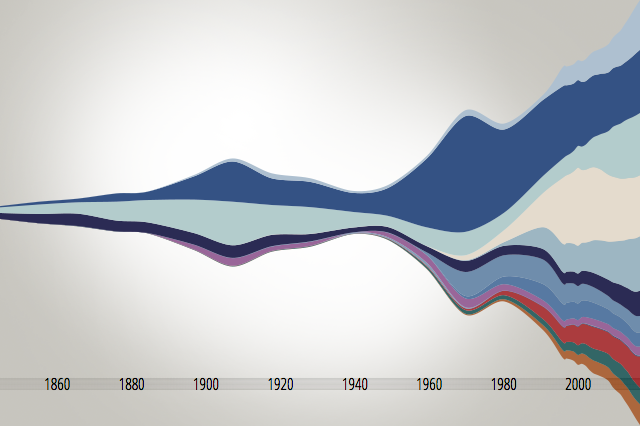

The graph below shows the number of international migrants by major area of destination and major area of origin (2017 figuresExternal link). [Flows have the same colour as their major area of origin. A small gap between flow and major area indicates the flow’s origin, a large gap indicates its destination.]

What does the pact aim to do?

Migration and Switzerland

Around one quarter of Switzerland’s 8.4 million residents have foreign passports, the majority from Europe. The percentage of Swiss people who have foreign roots increased slightly last year to 37.2%. This refers to anyone – foreign nationals, naturalised Swiss citizens, as well as Swiss citizens at birth – whose parents were both born abroad.

Last year, net immigration to Switzerland from the European Union was around 34,000, below record years like 2013 when 66,000 more people came from the EU than left. For 2018, net EU immigration through October was 26,809. Meanwhile, over 750,000 Swiss citizens live abroad.

States are not ratifying a binding global treaty. The compact is a non-binding multilateral instrument of cooperation that aims to set common principles and guidelines for orderly migration, thereby reducing irregular flows. The document was created after a lengthy review of migration data and a detailed consultation process.

It contains ten guiding principles and 23 objectivesExternal link. For each there is a long list of possible voluntary actions, which states can choose from. These include prevention measures to address the drivers of migration, fight human trafficking, manage borders and facilitate returns. It also focuses on solutions and best practices to facilitate regular migration.

“The strength of the compact is that it’s a very comprehensive and balanced document that takes into account both the serious legitimate concerns of those wanting to control borders and the rights of migrants,” Walter Kälin, a professor of international law at the University of Bern, told swissinfo.ch.

For Vincent Chetail, director of the Global Migration Centre at the Geneva Graduate Institute, the compact does not create new rules but reformulates existing ones. And although the compact is voluntary, he believes it can make a difference.

“A follow-up and review process will be established to assess the implementation of the compact,” said Chetail. “Even if it’s not legally binding, the UN General Assembly will meet every four years to assess implementation. There is a strong presumption on paper that these commitments will be taken seriously by states and implemented.”

More

Switzerland, land of European immigration

Who’s for it and who’s against?

The document was approved in July by 192 member nations at the UN General AssemblyExternal link including Switzerland but not the United States, which backed out last year saying the issue was “simply not compatible with US sovereignty”.

Since then, several other nations have rejected the compact ahead of the conference and others are hesitating. They include Israel, Australia, Austria, Poland, Slovakia, Bulgaria, Estonia, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, Hungary and the Dominican Republic. The Austrian government, for example, is concerned that signing up could eventually help lead to the recognition of a “human right to migration”. Italy, whose government has made headlines for its crackdown on migration, will decide whether to support the deal after its parliament considers it.

UN Special Representative for International Migration Louise ArbourExternal link and other supporters of the pact remain confident despite the withdrawals. She has called moves to reject the accord “regrettable” and “mistaken”. She says the compact does not affect states’ rights to manage their borders, but simply seeks to instil order into cross-border movements.

“It is in no possible sense of the word an infringement on state sovereignty – it is not legally binding, it’s a framework for cooperation,” said Arbour, comparing it to the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals for 2030.

Former Swiss Secretary of State, Peter Maurer, the current president of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), calls the pact a good compromise.

What’s the official Swiss position?

Ironically, the document that Swiss diplomats helped shape has turned into a political hot potato back home.

At the UN General Assembly in September, Swiss President Alain Berset gave the pact his personal blessing. On October 10, the Federal Council followed suit by giving its greenlight for the accord, whose “guiding principles and objectives correspond fully with Switzerland’s policy on migration”.

But against mounting resistance from politicians from centre and rightwing parties in Switzerland, the executive body has been reluctant to throw its full support behind the deal. Led by the wavering Foreign Affairs Minister Ignazio Cassis, cabinet decided to consult parliament on the document.

Then, one month after its go-ahead, the government announced it would not attend the Marrakech meeting as it had decided to delay adoption until the Swiss parliament had properly debated the issue.

On November 29, Swiss senators voted to give parliament the final word on the pact. The lower chamber – the House of Representatives – followed suit on December 11.

What are the views among Swiss political parties?

Politicians on the right and centre-right fear that the pact could blur the line between legal and illegal migration and undermine countries’ sovereignty. The conservative right Swiss People’s Party led the charge from September saying the pact is “incompatible with an independent management of immigration”. It warned that it could eventually take precedence over Swiss law and urged the government to reject it. In November, the conservative Campaign for an Independent and Neutral Switzerland group handed in a petition against the pact signed by 15,000 citizens.

The centre-right Radical-Liberal Party argues that the pact may be non-binding but as a soft law it has “political implications requiring extreme caution”. The centre-right Christian Democratic Party, which has several doubts, and the Conservative Democratic Party both want parliament to have its word on the issue.

Meanwhile, Christian Levrat, president of the centre-left Social Democratic Party, said Switzerland’s delay in signing the pact was a “political mistake”, both in foreign policy terms by aligning itself with countries like Hungary and the US, and nationally, as it was “bowing down to the People’s Party and the pressures it has exerted”.

For its part, the Federal Commission on Migration (FCM), a 30-member extra-parliamentary group that advises the government on migration issues, has said Swiss adoption of the compact is not only desirable, but “necessary”.

At this stage, the Federal Council continues to insist that the pact is in Switzerland’s interest and that it is not a treaty and thus the executive body should have the last word – not parliament. For now, the government has not ruled out a Swiss adoption, which could come later, according to the Swiss foreign minister.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.