Southeast Asia seeks new solutions to drug crisis

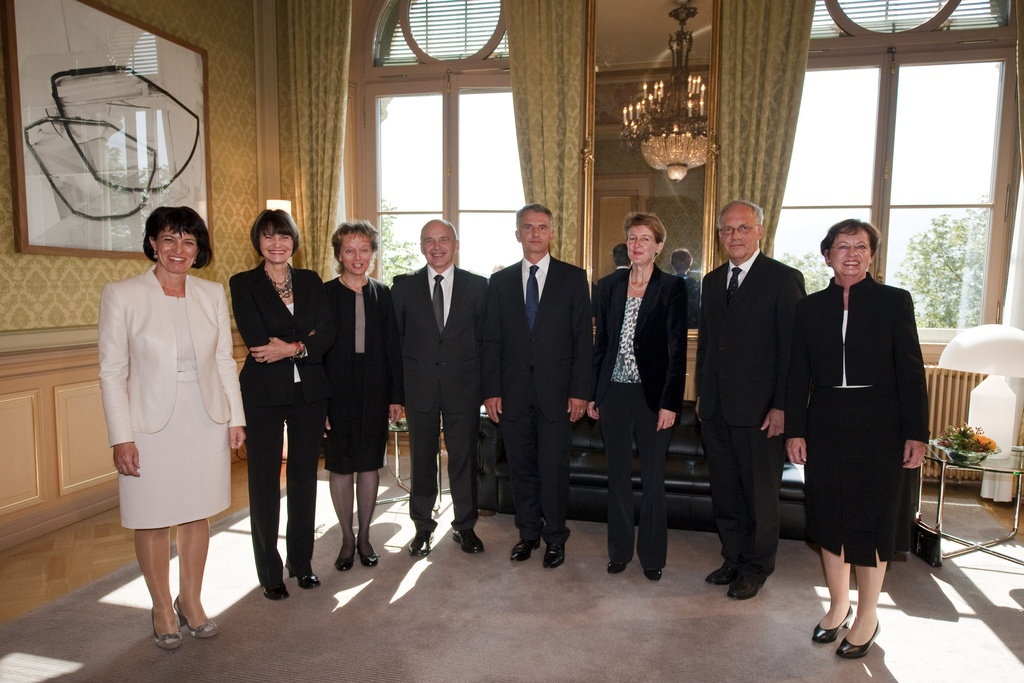

Former Swiss President Ruth Dreifuss, founder and president of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, recently returned from a trip to Southeast Asia. She tells swissinfo.ch that the policy shift in Thailand and Myanmar towards health-based solutions for chronic drug abuse is a notable evolution in a region long known for its “tough-on-drugs” position.

Established in 2011, the commission took its starting point from the position that the so-called war on drugs launched by former United States President Richard Nixon in 1971 had been a total failure, as drug trafficking has become more prevalent than ever and the number of users continues to rise.

However, Dreifuss says attitudes to tackling issues associated with illegal drug use are finally beginning to change.

swissinfo.ch: How far are Thailand and Myanmar willing to take their reforms?

Ruth Dreifuss: In these two countries, which are dealing with epidemics of HIV and Hepatitis C among those who inject drugs and the people they associate with, there is a willingness to develop public health policy. [This includes introducing] risk prevention measures such as making sterile injecting implements available and opening centres where health professionals can meet drug users and offer different services to integrate them [into treatment]. Methadone treatment is also beginning to see the light of day for those who are seriously drug dependent and, importantly, both Thailand and Myanmar are looking at ending coercive treatments based on abstinence, which are well known for being both degrading and ineffective.

There is also a clear awareness that punishments are too extreme. While there is no talk of abolishing the death penalty, it is no longer practised by these two countries. They want to start reducing the types of crimes for which this sentence is pronounced. This new awareness also concerns overcrowded prisons, which appear to be more like schools for educating criminals than anything else. So the scale for punishment will be reduced in these countries.

To do this, both countries are conducting wide-ranging consultation and information campaigns among the populations, which have trouble understanding these changes after 50 years of prohibitionist policy and suspicion of drug users.

Chair Dreifuss visited Ozone drop-in center and encouraged them in their key mission delivering services to PWUD pic.twitter.com/8WxObZuP3DExternal link

— GCDP (@globalcdp) 5 avril 2017External link

Remember that between 2001 and 2006, Thailand engaged in a war on drugs similar to that which is currently taking place in the Philippines. Thai police caused the deaths of several thousands of people through extrajudicial executions. And authorities in the country have had to recognise that this repression did nothing to reduce the trafficking or consumption of drugs – quite the contrary.

swissinfo.ch: Is it likely that other Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries could follow the same example?

R.D.: The big question is whether we can aim for a drug-free society. In Switzerland, this objective is still written into the laws on drugs. And it remains the objective of the ASEAN countries, which want to become a drug-free region. But is it still a possibility?

It’s clear that in the countries I have visited, even if their attitudes are still a bit hesitant, they have understood that a society without drugs is an illusion. Humans have always been attracted to psychoactive substances. From what right do we punish people who take substances that modify their humour, alleviate their pain, transform their perception and their consciousness of the world? Some substances have been culturally integrated such as alcohol, tobacco, chocolate, coffee or medicines – products which are also psychoactive.

Why should we, using state violence, persist in an illusion of humanity that would completely do without such substances? Why integrate some [substances] by regulating production and access, and prohibit others?

The international conventions which regulate the question of illicit drugs give countries the opportunity to find solutions which are adapted to their problems, to stop punishing users and develop public health policies, including those which allow for reducing the risks associated with accessing the black market for illegal substances.

However, these conventions do not authorise ratifying states to control the production of and market for drugs, as they do for legal psychoactive substances.

R.Dreifuss, Chair @globalcdpExternal link met with opium farmers, PWUD and harm red. advocates in Yangon pic.twitter.com/9pXbiTzM7sExternal link

— GCDP (@globalcdp) 10 avril 2017External link

swissinfo.ch: Is this change of course in Thailand and Myanmar symptomatic of a broader evolution?

R.D.: This is a general evolution. Even extremely regressive countries like China and Iran have developed substitution treatments and risk prevention programmes for dependent people.

But we’re also seeing regression, as in the Philippines. Certain countries stick to their firmly prohibitionist positions, like Japan and Russia. Moscow continues to practise a rigorous prohibition policy, with absolutely dramatic consequences for the Russian people. It’s the only country where the incidence of HIV continues to rise. In their prisons especially, and then outside, a strain of tuberculosis resistant to antibiotics is spreading widely. With its policy of repression, [Russia] forces every extremely dangerous activity to become clandestine. That said, a large majority of countries are looking for new solutions.

swissinfo.ch: Switzerland has for a long time been seen as a pioneer. Is that still the case?

R.D.: Switzerland did indeed respond innovatively when it was confronted with the HIV epidemic and increased instance of overdose. Since then, it has melted into the masses. Switzerland developed a public health policy which has proven to be effective. Now we need to develop additional measures to make it accessible to everyone who needs it. We should also integrate into the policy synthetic drugs which present new dangers and demand new responses.

But Switzerland is behind in terms of regulating drug markets and decriminalisation. Transforming the crime of consumption into a simple infringement is not just a half measure.

It must be remembered that repression policies around the world are always arbitrary, and in reality they target the poor, the most diminished areas, the minorities, including in Switzerland. So if the application of the law is arbitrary, we should change the law.

But there you have it. Switzerland has put so much emphasis on health and the proportionality of punishment that the question has pretty much disappeared from the radar. Political pressure for the more radical changes has largely disappeared. In addition, several initiatives in this vein have failed at elections, something which does not encourage parties to put the idea back on the table.

That said, there is quite a strong interest, including in large sections of the population, that cannabis production should be regulated and marketed and that banning it is neither effective nor useful.

The five priorities of the commission

• Put people’s health and safety first

• Ensure access to essential medicines and pain control

• End the criminalisation and incarceration of people who use drugs

• Refocus enforcement responses to drug trafficking and organised crime

• Regulate drug markets to put governments in control

Translated from French by Sophie Douez

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.