The challenges of marrying a nun during the Reformation

The letter which was delivered to the Oetenbach convent on September 30, 1527, changed Anna Adlischwyler’s life for ever. The author was Heinrich Bullinger, a priest and friend of Swiss reformer Huldrych Zwingli.

“You and you alone fill my thoughts,” Bullinger admitted to the young nun. He wanted to live with her and share everything – “the sweet and the sour”.

“You are young, and God did not give you your body for you to remain a nun for ever and do nothing to bear fruit,” he wrote. After singing the praises of marriage, Bullinger got to the point: “Read this letter three or four times, think about it and ask God to reveal his intention to you.”

This historical account is part of a series of swissinfo.ch articles marking 500 years of the Reformation. The origin of the Reformation is generally considered to date back to the publication in Germany of the Martin Luther’s 95 Theses on October 31, 1517.

Just a few years earlier such a love letter would have been unthinkable. But since the Reformation things were different, in Zurich too. Priests were getting married and nuns, who had devoted their lives to God, were turning their backs on life behind a convent wall. Even Martin Luther married a lady of the cloth who was 16 years his junior.

In Zurich, Zwingli had already been preaching since 1522 that life in a convent could not be justified biblically. Yet many nuns knew nothing else, because their families had taken them to a convent when they were children. Some nuns were outraged when the city government made Leo Jud their pastor, cursing that the devil had sent this “rogue preacher”, with one even threatening to “shit on his gospel”.

A bitter dispute over the souls of these pious ladies broke out between Catholics and Protestants. Catholic monks even tried using ladders to climb into nunneries to read Mass according to the old faith.

Stay or go?

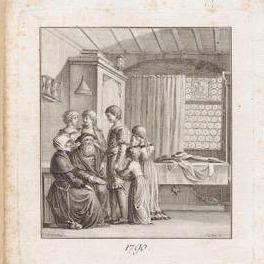

In the summer of 1523, the government decreed that the nuns had a choice: they could marry or live in an “honourable household” – or they could stay in a convent. Two years later, Oetenbach convent was officially closed.

Twenty-eight nuns opted for a secular existence. They were allowed to take their clothes and furniture with them, and the city returned the benefice that their families had paid to the convent. They were also paid the money they had spent renovating and decorating their cells.

Almost half of them found a husband pretty quickly, one even married the chaplain of Zurich’s GrossmünsterExternal link church. Not everyone was overjoyed, however. Many locals thought it was simply not on, a serious sin even. Defamatory poems were circulated, but no one knew who had written them.

Fourteen nuns decided to stay. From then on they had to wear secular clothes, attend reformed sermons and do work that was appropriate for “honourable women”.

One of these remainers was Anna Adlischwyler, who now had to decide whether to accept Bullinger’s offer of marriage.

Marriage court

In Grossmünster on October 29, 1527, the couple exchanged a promise to marry. A delighted Bullinger returned to his position in the Kappel monasteryExternal link, but Adlischwyler’s mother, a wealthy widow, was a fly in the holy ointment: if her daughter insisted on getting married, she could certainly do better than the bastard son of a priest. Her obedient daughter duly asked her fiancé to release her.

Bullinger was beside himself. In a letter he begged Adlischwyler to marry him and not make him look ridiculous. He then sent his friend Zwingli to try to change her mind. In vain.

Bullinger feared – not without reason – that Mrs Adlischwyler might promise her daughter to another man. He therefore appealed to Zurich’s marriage court. Anna Adlischwyler had to admit that she had promised to marry Bullinger, but added that she had always said she wouldn’t do anything against her mother’s wishes.

Yes or no?

Zwingli, who had been called as a witness, pulled out all the stops to help his friend. Anna had told him, he assured the court, that her mother “wanted to give her to a rich man, but she didn’t want that”.

In the summer of 1528, the court ruled that the engagement was binding and therefore “Anna should take no other man as husband other than Heinrich”. Nevertheless, Bullinger had to wait another year.

They eventually tied the knot six weeks after the death of Adlischwyler’s mother. On their wedding day, Bullinger gave her a letter he had written in which he assured his “Empress” that “now I have found peace, now I am happy if I can be with you, my dearest”.

The couple appear to have enjoyed a happy marriage and had 11 children. In 1531, Bullinger succeeded Zwingli as pastor in Grossmünster.

When Anna Bullinger died of the plague after 35 years of marriage, her husband was inconsolable. He told a friend: “You know that the Lord has taken my rock, my loyal, chosen and utterly God-fearing wife. But the Lord is just, and His judgement is just.”

Regula Bochsler

Regula Bochsler studied history and political science at the University of Zurich.

She has worked for many years as an editor, journalist and presenter for Swiss public television, SRF. She has made ten or so television programmes on history as well as putting on exhibitions.

Her books include “The Rendering Eye. Urban America Revisited” (2013), “Ich folgte meinem Stern. Das kämpferische Leben der Margarethe Hardegger” (I followed my star. The combative life of Margarethe Hardegger) (2004) and “Leaving Reality Behind. etoy vs eToys.com & other battles to control cyberspace” (2002).

(Translated from German by Thomas Stephens)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.