How 1968 changed Swiss schooling

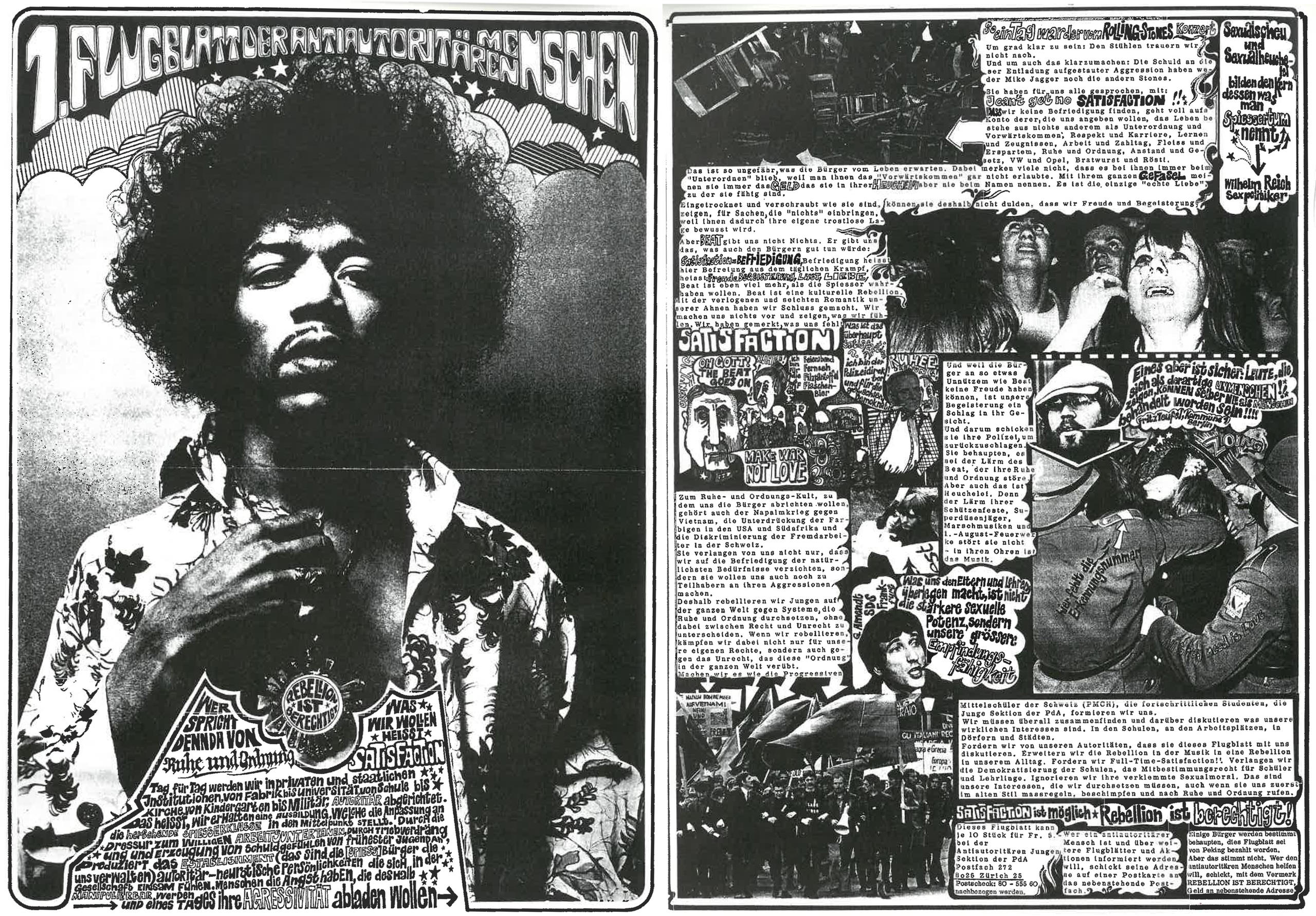

In the years around 1968, young Swiss felt a desire for new models of society and designs for living. That went for education too. Authority was in a deep crisis, and this was a time when experimental private schools sprang up.

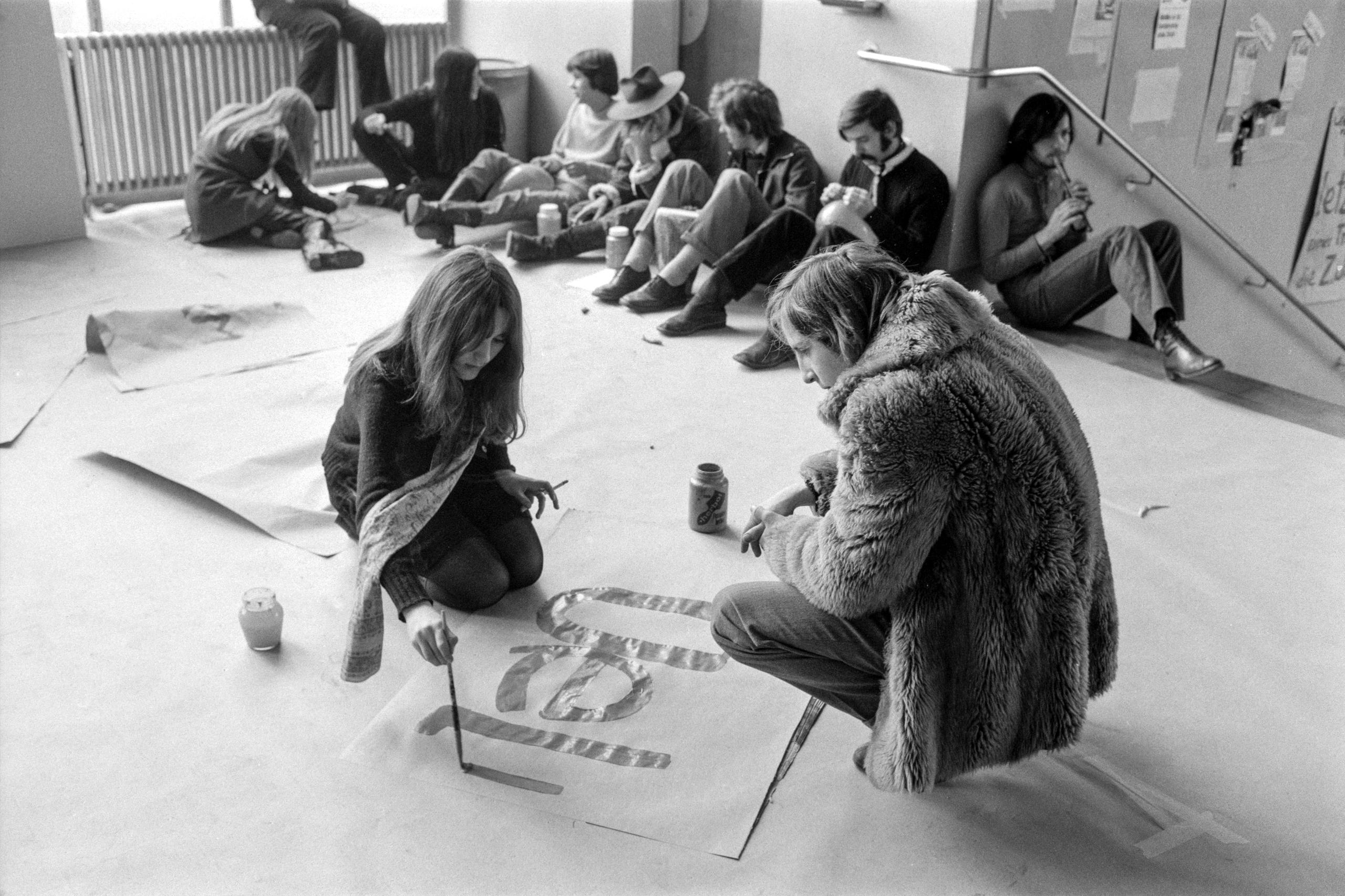

In Switzerland it was primary teachers in training who started the student revolt. In March 1968 about 250 of them who were enrolled in the teacher training college in Locarno occupied a classroom there. They demanded a new direction for teaching and input from students to be allowed.

After only three days the occupation was crowned with success. The education minister of canton Ticino met a delegation of the revolutionary students. The teacher training college in Locarno became the first institution in Switzerland to provide for input from students. In the summer of 1968 Marx, Engels, Freud, existentialist and anarchist thinkers were made part of the curriculum for the student teachers – but also Nietzsche and Tolstoy.

The relationship between the generations was changing in families too. People began to reflect on their relationship with their parents and on their own style of raising their children. Historians talk of a “psychoboom” in the 1970s. This was a time when parenting books became bestsellers.

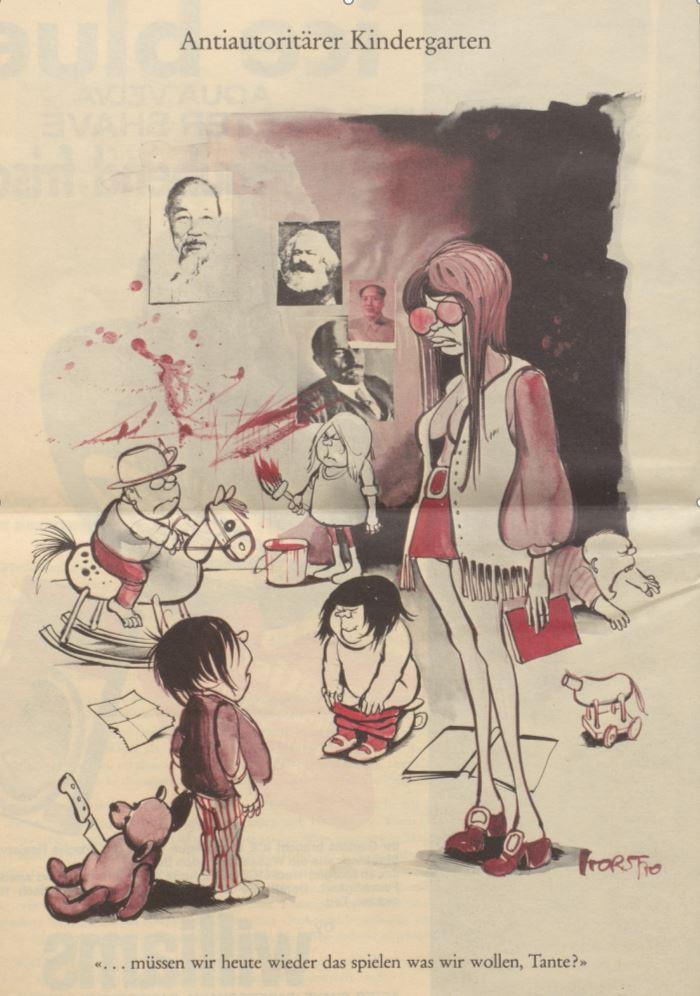

“Poisonous pedagogy”, which relied on the strap and unyielding discipline rather than dialogue, became increasingly marginalised. Even the large state-run schools began to change in the 1970s in response to the spirit of the times.

Summerhill

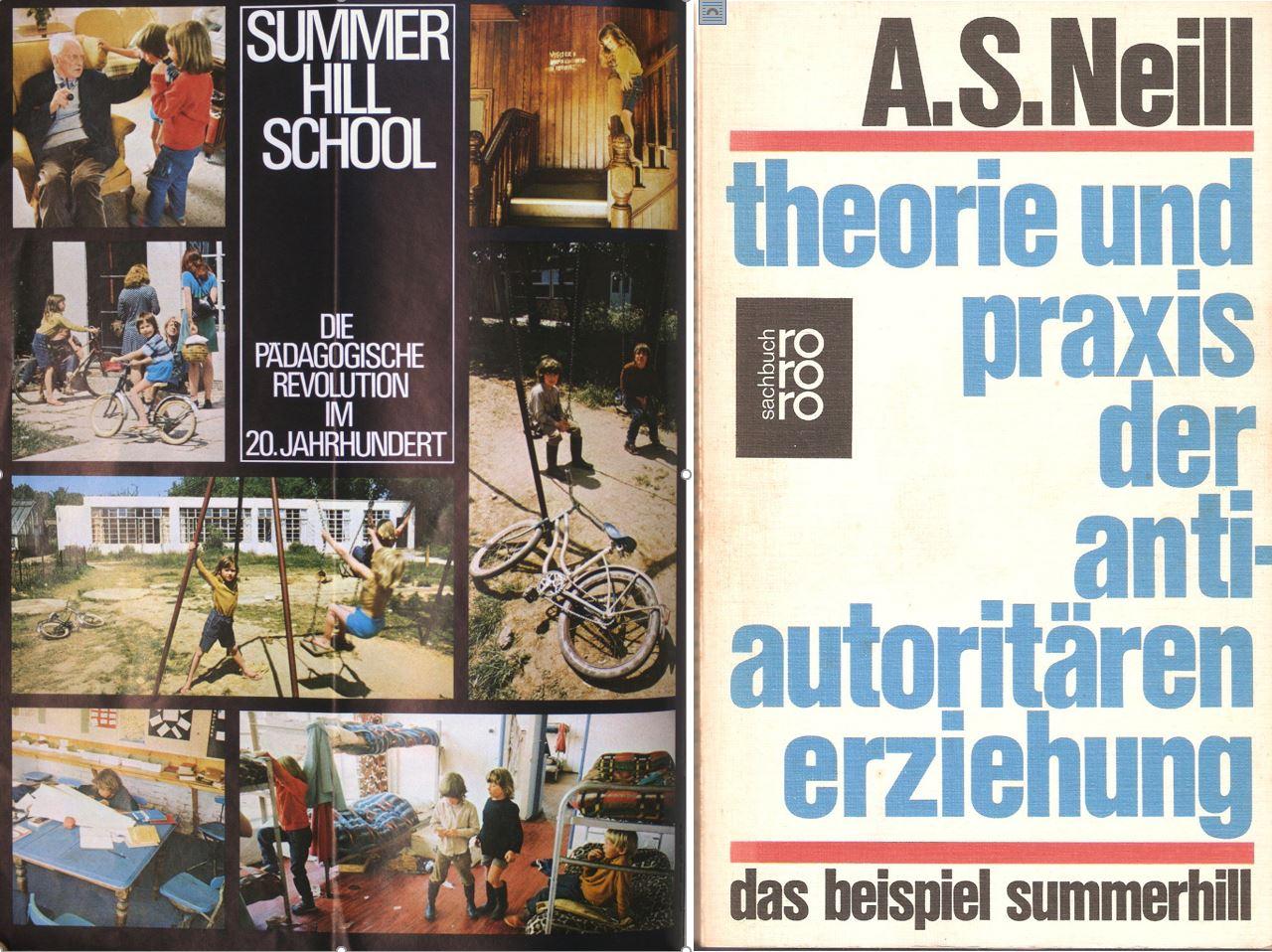

In 1960 the British educator A. S. Neill had published his book “Summerhill”. A German translation appeared in 1965 – to very little interest at first. But in 1969 the German translation was republished with the title “Theory and practice of anti-authoritarian education”. In the early 1970s nearly a million copies were sold.

The book defined what in Switzerland to this day is understood as “anti-authoritarian education” – although the term does not occur once in the book. The German publisher chose that title purely as a marketing strategy, wishing to cash in on the mood of 1968. It was an astute move. People from all over went to see Summerhill. Photographs taken at the time show children at the school cycling around on their bikes or going swimming – hardly ever sitting behind a desk in a classroom.

A Swiss journalist summed up Neill’s principles as follows: “For him education means being on the child’s side… For a child to develop well, it does not take rules and prohibitions, but recognition and love. Every punishment or humiliation is felt by the child as the opposite – as an expression of hate. The child reacts to that with hate, and thus grows up into an adult full of hate.”

Authority was in crisis. The traumatic experience of Nazi Germany had cast a long shadow on all sorts of authority figures: fathers, teachers, bosses. A sociological thesis was gaining ground to the effect that strict upbringing had made ordinary Germans into compliant tools of the Nazi regime. All authority now seemed to reek of arbitrariness, violence and cruelty. And by the late 1950s, there began to be pressure for change on educational policy.

Sweeping changes

By the middle of the 1960s, schools were coming to be viewed in a new way as places where hidden reserves of giftedness were waiting to be discovered – today one might talk about “developing human potential”. This created a certain amount of openness even among the official state institutions.

The year 1968 belonged, then, to a decade of sweeping changes, in which change was coming to be favoured by the institutions themselves.

In the wake of all the criticism of authority, however, some people turned away from state-run education after 1968. Swiss Waldorf schools, which had in fact existed since the 1920s when they were started by Rudolf Steiner, now experienced new growth. Other groups founded their own schools. One of the first such schools to open after 1968 was the “Independent public school of Trichtenhausen” in canton Zurich. It was run by a group associated with the film-making couple Alexander J. Seiler and June Kovach.

One of this group was Rolf Lyssi, who directed the most successful Swiss film ever, Die Schweizermacher (The Swissmakers). He wanted his own son, born in 1968, to “be allowed to develop his own individuality without pressure”. Lyssi did not condemn the state education system altogether; it had to more do with the “fine points”, he said.

There was criticism of the teacher-centred approach, frontal instruction, rigid desk placement – but also the preoccupation with marks. In the Trichtenhausen school, the pupils got to evaluate themselves. The main goal was an alternative approach to educating children.

Individualisation

Another goal was to provide an all-day programme, which allowed mothers to go to work – there was no public child-care then, and any creches had to be organised by the parents themselves.

Karin Seiler, daughter of Seiler and Kovach and a pupil at Trichtenhausen in the early days, particularly remembers the atmosphere of the place. There were no set classrooms; teaching was done as often out in the woods as in class. The furnishings were adjustable, the breaks were unscheduled and “everything just flowed in a relaxed way”.

The strength of this model of schooling lay in individualisation. If a pupil had problems, or caused problems, teachers just “devoted more attention to them, instead of punishing them”. Authority was not excluded, but it was the outcome of the interpersonal relationship and not the institutional standing of the teacher.

“Just because someone was standing up in front of the class didn’t mean they had to be right,” she said.

Anyone who wanted to send their kids to this school had to not only pay fees of CHF300 a month but also get actively involved. Parents and teachers met regularly for intensive discussions, as decision-making was based on grassroots democracy. Sometimes this meant discussion of fundamental principles, sometimes it concerned points of detail, such as whether youngsters should be allowed to plonk around on the piano or not.

‘Rather wild’

One-time principal Jürg Acklin says he always valued the vigorous and blunt kind of discussions that went on, even though they could be stressful. The school was an experimental “energiser”, and that had attracted him. He was brought in in 1975 basically to restore order.

“Things were happening in Summerhill fashion: they sat around the campfire with a guitar, the kids hadn’t learnt anything and even in third class they couldn’t read yet.” But improvements were soon brought about.

Primary schoolteacher Verena Vaucher was also hired at that time to bring some discipline and control to the “rather wild” school environment. She had begun her teaching career as a student teacher in the 1960s, when there was still corporal punishment. School inspectors would express approval if a teacher sometimes grabbed pupils by the hair or cuffed their ear.

It was the influence of the educational reform movement that finally made corporal punishment taboo for her. One of her main models was Neill – she was interested in how youngsters could be brought to want to learn. At Trichtenhausen she wanted to have a school free of fear that functioned without threats of punishment or regular exams and tried to impart to the children the joy of learning.

Vaucher gave pupils a say in making the daily schedule. She went on spontaneous school trips and put on theatre. The teachers were able to teach in an “experience-oriented” and imaginative manner.

The search for a more humane kind of education began long before 1968, of course. According to educational researcher Lucien Criblez, many Swiss educationalists even in the 1920s were more interested in free development of the personality than in imposing drill and discipline.

Yet in the years coming up to the Second World War, authority and leadership became major themes in the classroom again – even in Switzerland. But around 1968 little new was invented.

“Never order him to do anything – nothing at all. Do not make the suggestion that you might have the slightest authority over him.” That was not the credo of some alternative schooler with long hair in 1968, but one with an 18th-century wig: the Geneva thinker Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote the sentence in his book “Emile, or On Education” more than 250 years ago.

(Translated from German by Terence MacNamee)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.