Swiss undecided on shape of future army

The historic decision by Swiss voters to refuse the purchase of Swedish Gripen fighter jets on May 18 has called into question the role of the military – and particularly the air force. However, it is not a wholesale rejection of the armed forces.

“As such, the Gripen ballot wasn’t a vote about the army. Because if it had been, we would have lost,” said Jo Lang, a former Green Party parliamentarian and founding member of the Group for a Switzerland without an Army.

“It was a vote against the new jets and an increase in military spending. I also see it as a ‘no’ vote against the army’s arrogance, which reminded people of the times when the armed forces were untouchable.”

After the vote against the purchase of the Gripen fighter jets, the Swiss government has said it wants to slash the army’s budget for 2014-2016 by CHF 800 million ($891 million). The money could be made available to other ministries.

Funds for the purchase of the Gripen had already been set aside for this year and the next two years. In a statement, the defence ministry said it would not be possible to completely reassign the money at such short notice.

The ‘no’ vote has also called the army’s budget for 2016-2018 into question. The government will take a decision on this later in the year.

On the other side of the fence, Brigadier General Denis Froidevaux, president of the Swiss Officers’ Association, also believes the May 18 result was not a vote against the army.

“Pacifists and anti-militarists constitute around 30% to 35% of voters,” he said. “The remainder that helped the vote against the Gripen were casting a ballot either against the plane, Defence Minister Ueli Maurer or his party, the [rightwing] Swiss People’s Party. Or maybe they aren’t sure what they want or which direction our security policy should go.”

In Switzerland, security policy is regularly reviewed, and reports are issued every four years. The next one is due to be published in the autumn, but the officers’ association is worried it will be nothing more than a copied and pasted version of the previous report, released in 2010.

“We are finding it harder and harder to convince people of the need to have an army that can fulfill its three basic missions: to fight, defend and help,” Froidevaux said.

“There is no political consensus to start with. Some voters want to kill off the army altogether, some only want it to protect and help, while others want it to carry out all three missions.”

The pacifist Group for Switzerland without an Army was founded in Solothurn in 1982. Besides calling for the abolition of the armed forces, another of its goals was to promote peace.

It launched its first initiative demanding an end to the army in 1986, which was rejected by 64% of voters in 1989.

However, the group convinced the government that reforms were necessary for an institution that could still count on a force of 700,000 men at the time. That figure has dropped to 155,000 today.

In 1992, the pacifists were able to collect over 500,000 signatures to stop the purchase of F/A-18 combat jets. The following year, 57.1% of voters rejected the proposal.

In 2001, two other pacifist initiatives were rejected by three-quarters of voters, one calling for the abolition of the army, the other for the creation of a civilian service in favour of peace.

Its latest initiative, demanding the abolition of conscription, was defeated at the ballot box last September, with nearly three out of four voters refusing the proposal.

Besides launching its own initiatives, the group has also lent its support to other campaigns such as the one demanding stricter legislation for the purchase and ownership of guns, rejected by 56.3% of voters in February 2011.

Weaknesses

Army reforms have taken place regularly in recent years, but according to Hans-Ulrich Ernst, a former secretary-general of the defence ministry, those reforms were either thought up before the end of the Cold War or watered down by parliament.

“Those that were implemented were barely accepted […] and nothing has been done to deal with the army’s weaknesses,” he told swissinfo.ch.

To Ernst, the armed forces’ biggest weakness is their size. “Not so much the number of people serving, but rather the fact we have too many active soldiers and not enough reservists,” he added.

According to Ernst, Switzerland has two armies: recruit schools with trainee soldiers, and soldiers in active service. Out of 260 days spent serving, a Swiss soldier spends half of that time as a recruit.

“It’s a bad system, only applied by Switzerland,” Ernst pointed out. “The international standard is eight weeks of basic training.”

Lang also finds the Swiss army oversized and thinks it has been kept artificially large for ideological reasons.

“The army’s fundamental problem is that it cannot justify its size for security reasons,” he said. “Twenty thousand soldiers are needed for defence, but there are 100,000. The only reason for that higher number is to maintain mandatory military service.”

More

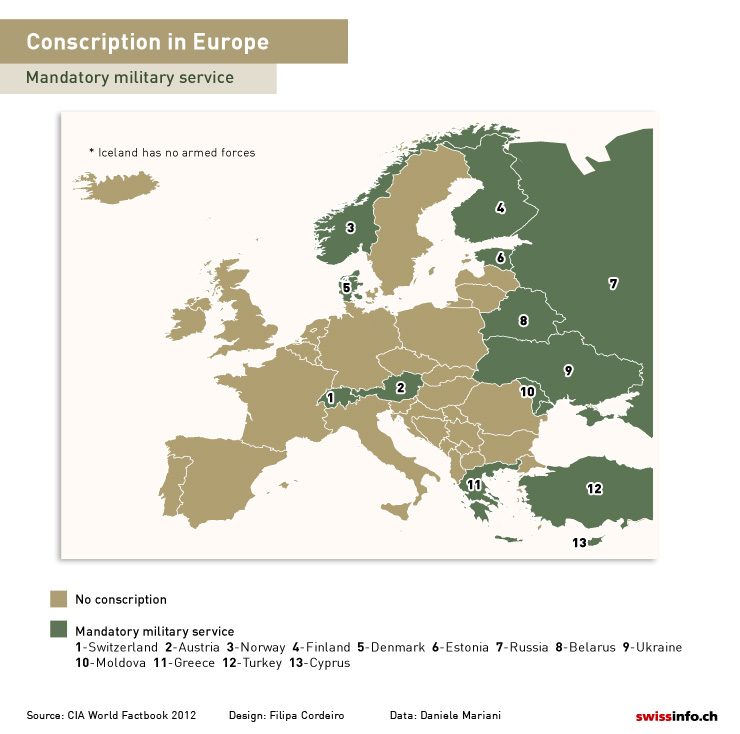

Mandatory military service in Europe

Foreign collaboration

The Swiss still want to keep conscription, though: three out of four voters decided last September to maintain it. While military service might not be an issue again for some time, more fighter jet questions are due to come up as the country’s 1970s vintage F-5 Tigers are retired.

The recent hijacking of an Ethiopian passenger jet to Geneva led some Swiss to believe that their air force was happy to delegate some of its missions to its neighbours in France, Germany and Italy outside of office hours – foreign jets, not Swiss, accompanied the hijacked plane to Geneva.

So why not join NATO?

“Switzerland has chosen to be neutral,” said Froidevaux. “And we can’t join an organisation like NATO without giving up our neutrality. Politically, it would be impossible to get voters to accept that.”

For Ernst, it’s a non-issue. “It wouldn’t matter if we were a member or not. Anyone attacking Switzerland from the sky or by land would [still] have to tangle with NATO. We managed to sneak on the train without paying for a ticket,” he added.

Christophe Keckeis, head of the army between 2004 and 2007, was quite irritated by the media coverage of the Geneva hijacking. “All people said was that we only operated during office hours. But nobody noted that our agreements with our neighbours worked perfectly and everyone did their job,” he said.

To sell a new fighter jet to Swiss voters, the former pilot believes that the population needs to be better informed about the air force. “Every day, around 3,500 civilian aircraft fly over our territory, and when some still don’t want to follow the rules, that’s when we get involved,” he pointed out.

That happens, for example, when an aircraft does not follow its flight plan or loses radio contact. Swiss fighters must then identify it, make it change its route or force it to land. “We have, on average, nearly one of those missions every day of the year,” said Keckeis.

(Adapted from French by Scott Capper)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.