Why the Swiss are experts at predicting avalanches

It may seem quite a leap from studying snowflakes with a magnifying glass to forecasting one of the greatest natural threats in the Alps, but the step is part of how Switzerland manages avalanches. The approach could soon win coveted Unesco cultural heritage status.

“What happens to fresh snow when it lands?” asks Gian Darms, an avalanche forecaster at the Institute for Snow and Avalanche Research (SLF)External link in Davos. Knee-deep in powder, his pupils stare blankly at each other. Whirring chairlifts can be heard in the distance.

“The arms of the crystals break off,” a bespectacled participant finally replies. “Well done,” says Darms.

The group of men in ski gear are standing in a snowfield just below the 2,692-metre WeissfluhjochExternal link peak in southeast Switzerland.

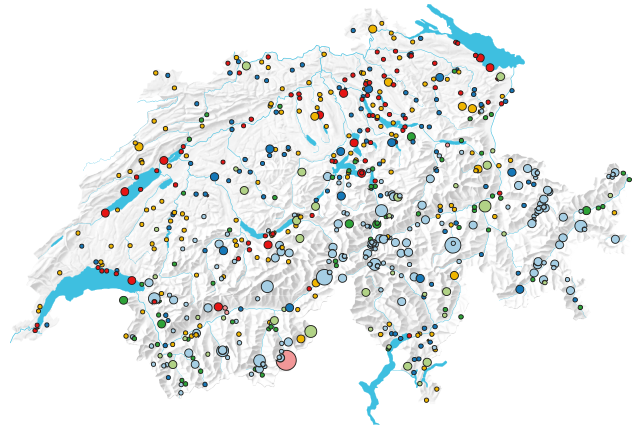

The eight students on today’s avalanche refresher courseExternal link – a mix of ski lift and communal employees and interested individuals – belong to SLF’s long-established avalanche observer networkExternal link. Since 1945, when SLF took over the job from the army, it has been responsible for producing a twice-daily national avalanche bulletinExternal link using data gathered by 200 people trained to do the job and 170 automatic measuring stations dotted across the Swiss Alps.

After gathering basic data on snow and weather conditions following traditional methods dating back over 70 years, snow shovels emerge from rucksacks and in less than a minute, the group has dug a deep trench to do a ‘snow profile’ to examine a cross-section of the snowpack. Kneeling, they stick their fingers into the snow searching for weak layers which could represent an avalanche risk.

“Can you see the round crystals? Does this fit today’s snowpack?” asks Darms. Hunched over, the participants peer at crystals from the different layers through magnifying glasses.

This video report by Swiss public television, SRF, shows how measurements are taken.

Handing down know-how

‘Managing avalanche danger’ is the focus of last year’s joint application by Switzerland and Austria for Unesco Intangible Cultural Heritage statusExternal link; a reply is expected in November. For their bid, the Swiss Federal Office of Culture insists that a “large and informal body of knowledge” on avalanches has passed on down through the generations.

“This traditional knowledge is being constantly developed, in that historic know-how is combined with the most modern technologies,” it argues.

Dating back to the Second World War, the SLF’s avalanche warning service is an obvious example of this knowledge transfer.

“My father was an observer for 35 years,” says Reto Wicki, a farmer from Sorenberg, a village surrounded by 2,000-metre peaks southwest of Lucerne. “I slipped into it seven years ago. I like the preciseness of the work, which is a typical [part of our] Swiss mentality.”

Over the years, observers have come from all walks of life – from monks to housewives – but are increasingly the employees of ski areas and local communes.

Working from November 1 to April 30, observers generally get up around 6am every morning to check for fresh snow and to gather other data, which is sent by computer to SLF and turned into detailed daily forecasts and models. Every two weeks they carry out snow profiles to see how the snowpack has changed over the winter and to check for weak layers. Observers are paid according to how much information they provide – on average around CHF3,000 ($3,000) for five months work.

“Other countries have observer networks but the density of our network and level of training and expertise is unique,” Darms claims.

He admitted, however, that inconsistency can be a problem, as well as finding replacements and getting measurements from remote areas. So why not simply swap humans for more automatic measuring stations?

“Humans not only observe but also interpret data. For example, an observer can see if snow cracks are appearing. At a certain altitude, there [could] be a gliding snow problem so we can anticipate things. The local dimension of assessing avalanche danger is a synthesis of information. This is something that a machine cannot do,” said Darms.

Research based on practical needs

The warning system is just one part of the avalanche management work carried out by the Swiss institute. From its origin in 1936External link, when a small group of researchers moved into the first snow laboratory on the Weissfluhjoch, the SLF has developed into a renowned institute with forecasting and research under one roof, and nearly 150 employees.

“The institute was founded based on practical needs because the hydropower companies, railways and tourism really wanted to be safe in the winter,” the head of SLF Jürg Schweizer External linkexplains.

“Originally, the Bernina Railway and the Rhätian Railway companies only got a licence for summer; they were not able to manage the avalanche risks. In the early 20th century, they were pushing for tourism and wanted to keep the roads open. Those were the practical demands that fostered greater research.”

Today, the institute boasts a myriad of world-class scientific projects from 3D avalanche modellingExternal link to lab-grown snow or the use of drones to map snowpack thickness. Every few years, the researchers test their theories and gather new data by triggering a huge avalanche at their test site at Vallée de la Sionne in canton ValaisExternal link (see video below).

Long written history

Announcing the joint candidacy last year, the Swiss Federal Office of CultureExternal link underlined that “the collective threat situation through avalanches has led to a common and identity-forging management of this natural danger in Switzerland and Austria”.

SLF experts admit that the experiences of avalanches gained living in the Swiss Alps may not be that different from those in Austria and France. But what makes the Swiss approach to managing avalanche dangers so unique is its long history – much of it written down – and the level of sophistication.

Books such as the Die Lawinen der Schweizer Alpen [The Avalanches of the Swiss Alps (1888)] and Statistik und Verbau der Lawinen in den Schweizeralpen [Swiss Alps avalanche statistics and prevention measures (1910)] by Federal Chief Forestry Inspector Johann Coaz are still regarded as invaluable reference documentsExternal link by practitioners, especially for the creation of hazard maps.

“I’m not aware of comparable documents in Austria,” said Schweizer, who believes Switzerland’s knowledge of managing avalanches is ‘more structured and developed’ than that of its neighbour partly due to different governance structures.

“In the 19th century, Austria was an empire. I’m not sure how well the villages were taken care of but here in Switzerland there was always a strong sense of self-organisation, as the villages were more or less independent.”

Tragically, avalanche experience and skills are also formed by real disasters and accidentsExternal link. The avalanche winter of 1951 resulted in almost 100 deaths, and marked the beginning of organized avalanche mitigation in Switzerland, says Stefan Margreth, a civil engineer and specialist in protection measures.

“That’s when avalanche bulletins, hazard mapping and mitigation projects really took off,” he explained. The first avalanche hazard map was created in Switzerland in 1954. Defence structuresExternal link such as steel bridges and snow nets sprouted across the Swiss Alps above protection forests. Today, they stretch over 1,000 kilometres, protecting key locations like the town of Davos.

Yet despite these advances and a growing body of knowledge, experts admit that avalanches are extremely unpredictable and many scientific questions remain unanswered, such as how a crack develops in the snowpack.

“Avalanches are very complex. Today, it’s not possible to say on what slope you will have an avalanche tomorrow – nobody really knows,” said Margreth.

Intangible heritage

After Basel’s Fasnacht carnival and Vevey’s Fêtes des Vignerons winegrowers’ festival, Switzerland’s management of avalanches could this year receive coveted Unesco intangible cultural heritage status, which celebrates well-known traditions, art forms and practices.

Switzerland is also currently home to 12 UNESCO World Heritage sitesExternal link – nine cultural and three natural – including the Lavaux vineyards, St Gallen Abbey and Bern Old Town.

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.