Graubünden at 500: a look back at early modern democracy

Canton Graubünden in eastern Switzerland is celebrating its 500th birthday this year. History professor Randolph Head sheds light on the evolution of democracy in the pioneering canton and explains how democracy used to work without the concept of equality.

Randolph Head teaches European History at the University of California, Riverside, and specialises in the history of Switzerland. In his dissertation, he wrote the first modern history of early modern democracy in Graubünden spanning from the 15th to the 17th century.

SWI swissinfo.ch: Graubünden is marking its 500th anniversary this year. What do you think is important for the people of the canton to remember?

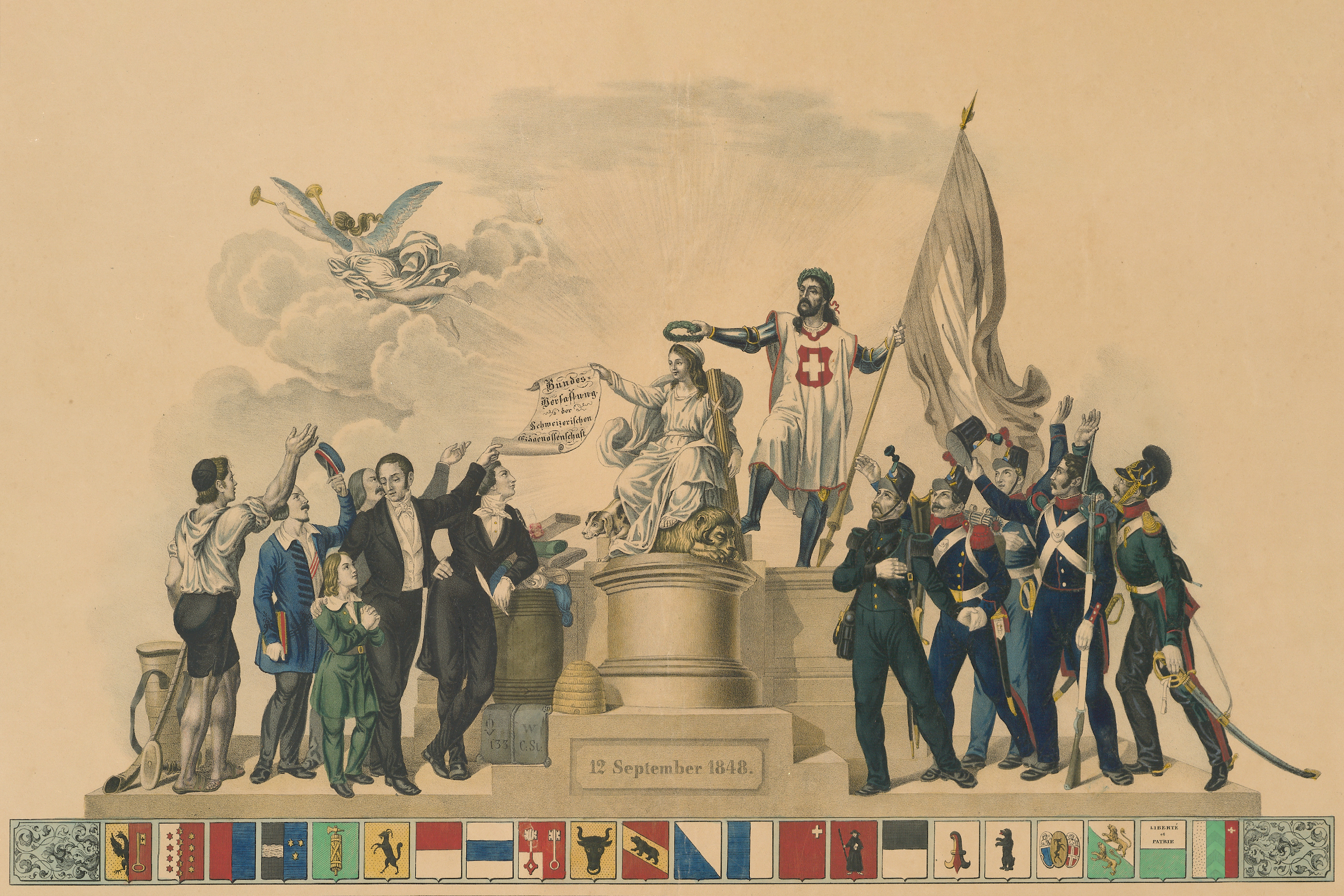

Randolph Head: In our modern world of sovereign states we want to celebrate their origins. For example, the establishment of canton Graubünden as a unified entity and the Republic of Three Leagues dates back to 1524. Prior to that, several attempts were made to unite the communities in the region by signing various agreements and forming alliances, but they all failed to find a common denominator. [With the 1524 treaty] Graubünden was one of the first regions to achieve unification, and it was not until the 19th century that it joined the Swiss Confederation. The alliance survived the Reformation and the uprisings of the 17th century, albeit barely. This was pretty special.

SWI: How did a professor from California write the first modern history of Graubünden’s early democracy?

R.H.: When I was a child, I used to visit my grandmother in Bad Ragaz in canton St Gallen from where I could see the mountains of Graubünden. They always looked very dramatic from down there. The quirky names of the Graubünden villages such as Trins and Truns also fascinated me. When I decided to study history at the age of 28, I was more interested in Chinese history. But as my professors seemed to think I was too old to learn Chinese, I thought: “Oh well, my mother is Swiss, and I speak German.”

In 1524 the Republic of the Three Leagues was formed which unified three separate alliances known as the League of God’s House, the League of the Ten Jurisdictions and the Grey League.

Graubünden is Switzerland’s largest canton by geographical size and lies in the southeast of the country. It is the only trilingual canton (German, Romansch and Italian).

Before becoming a canton in 1803, the Three Leagues had various interactions with the Swiss Confederation but were not formally part of it.

One day, I was looking for names of cantons in the Houghton Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and found names like Aargau, Zurich and so on. When I came across Graubünden, I stumbled upon a propaganda pamphlet from 1618. It was the attempt by some clergymen to justify the actions of the criminal court of Thusis. It was one of the many notorious criminal courts in Graubünden that were established during the religious conflicts and were fuelled by the big powers at the beginning of the Thirty Years’ War. The first paragraph of the pamphlet read: “The form of our regiment is democratic.”

SWI: This is very clear terminology.

R.H.: Yes, and very unexpected in 1618! It would be a bit like Washington stating in 1955 that the form of the US government was communist. Back then, the term “democratic” was considered an insult. If you wanted to slander an enemy of the ruler, you would call them a democrat. In England, there was an array of books railing against alleged democrats such as the Presbyterians who demanded self-determination in church, or the Jesuits.

Aristocrats in England also regarded the Swiss as democrats: over in Switzerland they said they saw the cancer that self-determination would lead to.

SWI: What is democracy as we understand it today?

R.H.: I have been thinking about this quite a lot recently. Today, there are definitely more antidemocratic views in politics than when I was researching Graubünden. The first thing I realised back then was that democratic systems and conditions can be entirely different in different societies. Graubünden was an early modern democracy, not a modern democracy. Today’s democracies are, at least in theory, based on universal human rights. However, the expression “all men are created equal” from the American Declaration of Independence did not exist in the early modern era. In early modern politics, even in democracies, the principle of human equality did not exist. It was rather the opposite that prevailed, namely the principle that people are unequal.

More

Sister republics: what the US and Switzerland have in common

SWI: Were the people of Graubünden proud of the democratic form of government?

R.H.: Most people in Graubünden ranging from aristocratic families to the poorest farming families from the Surselva region didn’t even know what the word meant. In the 16th and 17th centuries only a few people had such understanding. But the people of Graubünden were certainly proud to be “free” which equalled “privileged” in the early modern era. They had certain privileges and were masters over others. And it was better to be a lord than a subject – that much they knew.

SWI: So, the people of Graubünden are actually celebrating 500 years of freedom in 2024?

R.H.: Graubünden was formally part of the Holy Roman Empire, but there was little evidence of this in everyday life. They were subject to the emperor, but this didn’t mean much as the people of Graubünden considered themselves privileged. They were under the authority of different lords, and the liberties they were granted depended on their lords. Theoretically, the emperor was legislator and highest judge at the same time within this hierarchy of inequality. Separation of power didn’t exist in any of the early modern European systems, but by placing certain people above others, the emperor separated the powers between individuals. This hierarchy of inequality allowed the canton of Graubünden to lay the foundation for its early form of democracy.

SWI: How was inequality used politically?

R.H.: Before the Thirty Years’ War, a tract in Graubünden listed several reasons why the canton was allowed to force its Catholic subjects in Val Telline to change their faith. First, Graubünden was democratic; second, the majority of democratic Graubünden was Protestant; and third, ius reformandi, which stipulated that the religion of the territorial lord determined the religion of his subjects, prevailed.

According to the tract, the people of Graubünden had the right to convert the people of Val Telline – by force if necessary. However, this argument only stood because Graubünden was democratic, and the people of Val Telline were their subjects. This is how democracy was used to gain power over others.

SWI: In your dissertation you also describe a very populist rhetoric, namely that the elite were kept under control by the people.

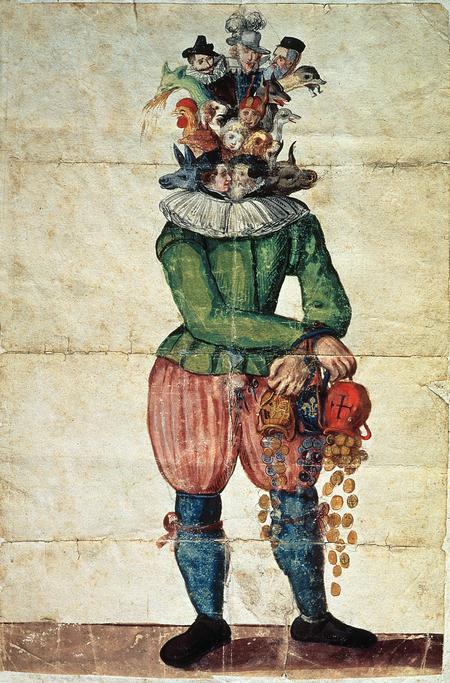

R.H.: This is particularly evident in public gatherings where armed militia met and formed a criminal court. It frequently happened that the wider public was involved in settling a dispute between elite factions. However, the wider public was often of the opinion that everyone was equally bad. A 1576 protocol of such a gathering of the Three Leagues states “that all effort is in vain, and nothing will get better with ‘our big merchants’”, that is the canton’s influential families.

Hence, let’s start a riot and “cut everybody’s head off”. In the 16th century various “big merchants” had to stand trial several times, were exiled or even executed. The notion that the common people did not want to become part of the elite but wanted to control and discipline them runs like a thread through Graubünden’s early modern history.

The wider public demanded that state affairs were conducted in the interest of the community, namely modern, transparent and fair. But the common people were not keen to conduct state affairs themselves. Those who didn’t have to earn their living as a blacksmith or farmer were chosen to deal with the government – in Graubünden and elsewhere in the Swiss Confederation.

SWI: The open-air voting of these early democracies is rather irritating. Secret ballots did not exist. Did they simply never consider the concept of secret ballots?

R.H.: They hardly ever thought about it. With open-air voting you do not gain the right to vote based on your individual freedom but because you are a member of a community. The reason behind it was that all voters had to publicly justify their vote.

The most important goal was to achieve consensus and show the will of the community as a whole. Division was always a risk. [In these open-air votes] people did not only elect bailiffs and governors or formulated laws and declarations of war, they also demonstrated unity. If you want to be a cynic, you could argue that open-air votes were a lot easier to control. People were also pressured to go along with the majority. Sometimes this pressure was very brutal, sometimes it was exerted through bribery.

SWI: Were there never any close election results?

R.H.: Hardly ever. After the Reformation, parishes were allowed to elect or dismiss their own clergymen. In other words, each parish could de facto decide whether it wanted to join the Reformation or not. There are some beautiful folk tales about it, even though not all of them are entirely credible. One such tale is described in Emil Camenisch’s book Bündner Reformationsgeschichte (Reformation History of Graubünden) which was written in 1920: there used to be a village – it could have been Fellers, or maybe Schleuis – where the number of Reformation supporters and Catholics was exactly equal. One day, a woman gave birth to a boy, which gave the Catholics the majority.

SWI: Was the baby allowed to vote?

R.H.: No, but as it was a boy, he became part of the new majority. This was what early modern democracy was all about.

Edited by David Eugster. Adapted from German by Billi Bierling/ts

More

Even the world’s best democracy isn’t perfect

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here . Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.