Drinking like a Swiss

It may be hard to believe now, but in the 17th century, the Swiss had a reputation for being a nation of heavy drinkers.

An exhibition at the Forum of Swiss History in Schwyz in central Switzerland shows how drinking habits have changed over the centuries, and includes a look at Swiss inventions such as Ovaltine and a short-lived attempt at cola.

“Drinking is their passion, their delight, their biggest expense. They drink together, they bargain together while drinking and even conclude the most important business [when drinking],” the French diplomat Daniel L’Ermite wrote about the Swiss in 1601.

He was not the only foreigner to be astounded about the Helvetian fondness for a glass. “To drink like a Swiss” was a common 17th century saying.

“It was wine that was drunk the most in the 17th-19th centuries, water of course as a basic drink, but a lot of wine,” said Pia Schubiger, curator of Bottoms Up – The History of Drinks and Drinking in Switzerland, which runs at the forum until March 7.

Water was not always clean and was therefore suspect. So wine was served with every meal in the cities, with even the poor receiving a daily ration in the hospitals. Country folk tended to drink after work or on special occasions.

Vines were commonplace across the country, with red wine primarily being made in the east of the country and white in the west.

Tea arrives

In 1900 Swiss inhabitants were said to consume around 15 litres per head of alcohol, with men drinking approximately three times more than women.

This partly had to do with the fact that drinking parties, as described by L’Ermite, were purely male affairs. But this was soon to change.

“In the 18th century, drinks such as coffee, tea and chocolate appear and they were first of all consumed in the cities and by the wealthy,” Schubiger told swissinfo.ch.

“Chocolate was served to people’s bedsides, people drank afternoon tea. Here men and women and families drank together, new forms of drinking together appeared.”

One of the pictures at the exhibition shows a proud Bernese aristocratic family showing off their fine teapot and dainty cakes.

Wine bug

There was another factor. In the 19th century, European vines were ravaged by the Grape phylloxera bug, accidently brought over from the United States.

“Here in German-speaking Switzerland more beer was consumed, this has to do with the fact that the beer making technique got better. But people in the French-speaking part continued drinking wine,” the curator explained, adding that people in French-speaking areas replanted with bug-resistant United States vines. This difference still persists today.

That’s not to say that alcohol was banished to the sidelines in the 19th century. Drinking still played a big part in men’s associations and also in creating national identity in the fledgling Swiss state.

“With the shooting festivals there was the idea of celebrating and drinking to the republic together. Hundreds of people gathered, families too, at these festivals. Speeches and a common toast were made,” Schubiger said. Indeed, paintings from the time show huge halls full of people, drinking and making merry.

Army tipplers

But high alcohol consumption, prompted also by industrialisation and the appearance of cheap tipples from abroad, started to cause the authorities concern. Abstinence campaigns were launched. “My Daddy doesn’t drink fruit brandy,” says one typical poster from the 1930s.

Attitudes were also changing. Drinking became less acceptable during working hours. This is well illustrated by the example of the Swiss army, where it was until the end of the 19th century customary for soldiers to receive five decilitres of wine a day as their daily ration.

“And perhaps a brandy when there was bad weather or a long march,” added Schubiger.

Afterwards the rules stated clearly that no alcohol was to be consumed during the day. Drinking in the evening was allowed but only in moderation.

Swiss cola

Alcohol-free drinks were also launched, really taking off in the economic prosperity after the Second World War. In Switzerland there was Elmer Citro and Pepita. The Swiss attempt at cola, Vivi-Cola – which came out in 1938 and is fondly remembered by some Swiss to this day – had mostly fizzled out by the 1960s.

Other Swiss inventions had more success, with the Swiss firm Nestlé inventing soluble coffee.

Ovomaltine – or Ovaltine as it is known in English-speaking countries – the malt chocolate drink, also has an enduring appeal. Schubiger said its development had very much to do with attitudes to milk.

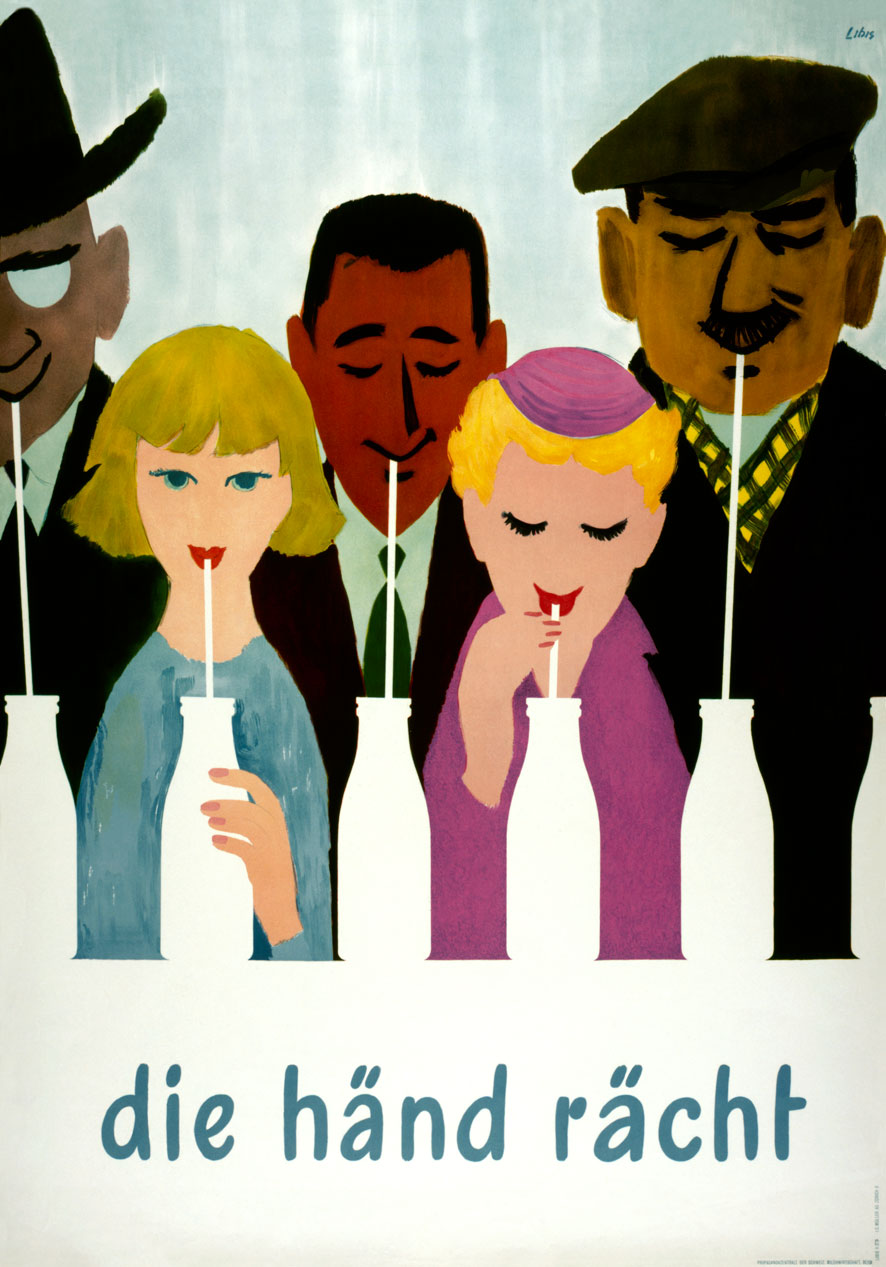

“In the 18th century milk was not really considered a typical Swiss drink, this developed towards the end of the 19th century when it was decided that everybody should drink milk because it was very healthy and very Swiss,” she said.

“Then came the idea of Ovomaltine which flavoured the milk and this was made into a processed foodstuff par excellence.”

Modern habits

Mineral water – of which the Swiss consume an average 115 litres a year – started to become popular after it was filled into bottles, also from Swiss springs.

Nowadays it is difficult to characterise Swiss drinking habits. Wine is still popular, as is beer. At breakfast most people drink coffee or hot chocolate, says the curator.

“There’s a trend towards individual drinking, with the arrival of plastic bottles which you can take out of your rucksack at any time and take a sip. But people also continue to drink together,” Schubiger explained.

So although the Swiss may not now have such a reputation for drinking as their forebears, you will at least still hear much clinking of glasses – alcoholic or not – across the land. “À la votre, Zum Wohl, Salute!”

Isobel Leybold-Johnson in Schwyz, swissinfo.ch

Bottoms up – The history of Drinks and Drinking in Switzerland is being held in the Forum of Swiss History in the central Swiss town of Schwyz.

It runs until March 7, 2010.

It was first held at the Prangins Castle museum near Nyon in 2008-2009 to celebrate its 10th anniversary. It has been widened to encompass local tastes in Schwyz.

Drink: One can give this name to all fluid food aimed at restoring our forces; this definition does not exclude fluid remedies. The aim of a drink is to be a remedy to thirst, drying out, thickening or acrimony of the humours. Cold water, very light, odourless and without taste, drawn from the river, is the most healthy drink for a hardy man.

Wine: This is a liquid pressed from grapes which is allowed to ferment to make it drinkable… the excessive abuse of wine extinguishes little by little our natural warmth, whereas its moderate usage makes us happy, bold and vigorous.

Cafés: These are establishments in which the usage of coffee takes place: one partakes of all sorts of liquids there. These are also the makers of our moods, both good and bad.

Chocolate: The usage of chocolate does not merit all the good or the bad things that have been said about it. This type of food becomes more or less bland with use… Long ago chocolate was called old people’s milk; it is considered very nourishing and very suited to awakening the languishing forces of the stomach.

(Source: Yverdon Encyclopedia, 1770-80)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.