Italy’s crisis to have strong impact on EU

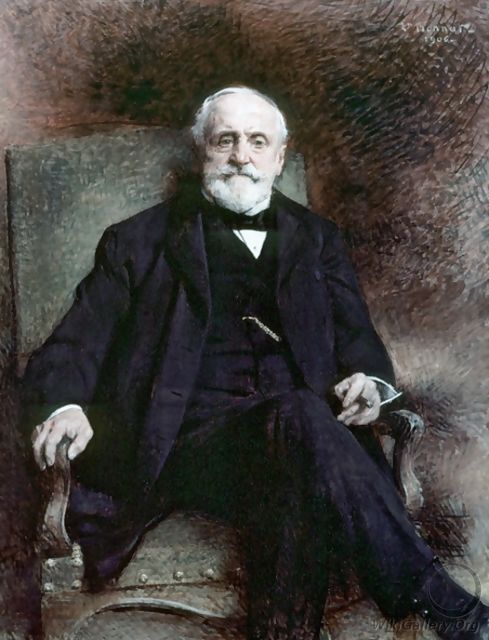

Italy and other European Union countries should invest rather than adopt austerity measures in this time of economic crisis, says Swiss expert Sergio Rossi.

As Italy’s economy descends into turmoil, Rossi, a professor at Fribourg University, says that the country’s political instability and inability to come up with a long-term growth strategy are particularly worrying.

In the coming days, the Italian parliament should decide on an EU-required financial stability law to reduce government spending and help boost its ailing economy.

swissinfo.ch: Berlusconi insists that Italy is not Greece, but both are in trouble.

Sergio Rossi: It’s correct that Italy has greater economic capacity than Greece, just look at what is going on in design, fashion, advanced technology and renewable energies. Italy’s economic potential is enormous but its political instability weighs it down. Businesses are confronted with absolute uncertainty and also a very high tax burden because of tax evasion.

swissinfo.ch: Italy is Europe’s third largest economy. If it collapses, could it take the EU with it?

S.R.: After Greece’s collapse and the problems in Ireland, Portugal and Spain, if Italy doesn’t manage to pay back its government debt on time, then the main foreign creditors – French and German banks – are going to find themselves in financial trouble too.

Italy is supposed to pay back around €300 billion (SFr370 billion) in 2012. If it can’t, this will affect international financial stability much more than Greece, as Greek government debt is a lot smaller than the Italian one. It will thus be purely up to Germany to finance the bail-out fund. But if it has to pay for all the other countries, the intergovernmental aid system won’t be able to stop the collapse of the euro zone.

swissinfo.ch: People have been talking about a decline of the euro zone.

S.R.: Returning to old national currencies will only make the situation worse. The euro – which would remain the currency in the more stable countries – would get stronger on the exchange markets, German exports would plummet and the euro zone would slow down even more. There is also a legal problem. If Italy has debts in euros, what exchange rate would be used to pay off its debts if it went back to the lira?

Going back to national currencies is just too unsure for both debtors and creditors. It’s a serious situation but this doesn’t mean hasty decisions should be taken. The euro zone should continue to be made up of 17 countries but should strive for better integration. It’s like in a big family, if one member has problems, you don’t throw them out but you support them with solidarity.

Germany must understand that it’s in its own interests to help Greece and Italy because these are two important export markets for German firms. If the crisis continues, even Germany’s economy will take a sharp hit.

swissinfo.ch: How can Italy exit the crisis?

S.R.: The markets will continue punishing Italy until Berlusconi goes. His politics are not very credible, his promises weak and the EU no longer trusts him. We saw this at the G20 in Cannes where Italy was put under International Monetary Fund monitoring. But doubts remain about what happens post-Berlusconi. We don’t know whether the measures Berlusconi agreed with Europe will be carried out by the new government credibly and in time.

For its part, the European Central Bank should buy Italian government debt bonds on the primary market and use them as parachutes. This would considerably reduce the insolvency risk and interest rates would be less exorbitant for Italy. This would be a strong signal for the markets.

swissinfo.ch: And what should the EU do to regain stability?

S.R.: For years German, French and Irish banks lent huge sums to countries such as Greece, Spain and Portugal without worrying about how they were used. Taking advantage of the low interest rates, the debtor countries financed family and state consumer spending instead of investing and creating revenue, jobs and tax yield. These tax resources could have been used to pay back government debts in time as this is logical and what is owed to creditors. The euro zone crisis is systematic and the only solution is to cancel out a large part of the debts given that these debts are, in a majority of cases, not going to be paid back.

By adopting austerity plans for its members, the EU is taking an accounting approach, balancing government accounts regardless of the economic situation. To ensure long-term economic growth in these times you must avoid austerity programmes and focus instead on more investments in training, research, public services and transport infrastructure. The EU has now entered into a lost decade and getting out of it won’t take three months, or even three years.

Italy has Europe’s third largest economy but its government debt stands at €1.9 trillion ($2.6 trillion, SFr 2.3 trillion) the equivalent of 120% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP).

According to the Italian economic ministry’s forecast of September, growth will stop at 0.7% by the end of the year, and drop by a further 0.1% in 2012.

By comparison, Greece has a government debt equivalent to 189% of GDP, France has 86.2% and Germany 83.2%.

Italy has the world’s third largest gold reserves by country after the United States and Germany at 2,451.8 tonnes.

Italy has been downgraded by credit ratings agencies and since the beginning of November is being monitored by the European Union and the International Monetary Fund.

Over the next days, the Italian parliament is due to decide on a financial stability law for the country which has been requested by the EU. The law should reduce government spending and help boost the economy.

European markets reacted negatively to the announcement that Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi is to resign after the vote on economic reforms.

Yields on 10-year bonds were up at 7.35 per cent on Thursday, well above the threshold that forced Greece, Ireland and Portugal to seek bailouts.

(Translated from Italian by Isobel Leybold-Johnson)

In compliance with the JTI standards

More: SWI swissinfo.ch certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative

You can find an overview of ongoing debates with our journalists here. Please join us!

If you want to start a conversation about a topic raised in this article or want to report factual errors, email us at english@swissinfo.ch.